A lot of spirituality and religion is formed by archetypes that connect with the deep recesses of our subconsciousness. These images aren’t indoctrinated or societally suggested – they come from dreams and intuition, a clear understanding that the world is touched by the immaterial and supernatural, that god speaks through his creations. And thus, these images return in multiple religions and iterations – different, yet the same, magnets of repulsion and desire.

Haley Fohr is no stranger to the immense power of imagery and the immaterial. For each record as Circuit des Yeux, she chooses a colour to embody her life, in which she dresses, lives and eats. In Plain Speech chose a lush green, the physical spirit-quest of Reaching for Indigo came in a deep blue, and the upsettingly torturous elegy of -io came in bright orange. For each of these cycles, Fohr fully reconceptualized herself, imagined a reality that would birth her vision of existence and embodiment in a way that’s maybe only comparable to the likes of David Bowie and his acolytes.

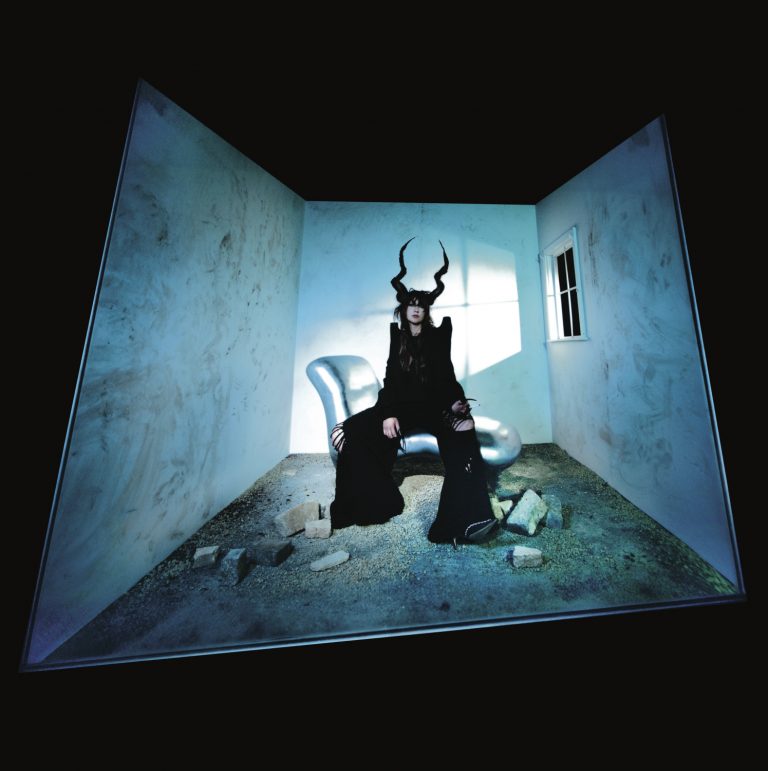

While Halo on the Inside, her newest album, comes in a rich turquoise shade, that colour merely seems to frame Fohr’s presence in all black, horned, coal eye shadow burying her pupils. This is something new altogether – a conscious embodiment of Pan, whom Fohr became fascinated with after a trip to Greece, as gothic Amazon. Now, Pan is an interesting one: half human and half goat, mischievous and liberated, he’s a trickster that resurfaces throughout culture in different guises. There’s the namesake Peter, who seems a spiritual adaptation of folklore into pop-culture, shedding horns and hooves but embodying the figure. There’s the Faun, which Guillermo del Toro cut into the bark of the 20th century. And then there is Satan – always Satan…

Altogether, these horned figures pose the same question: what if humankind sheds its societal shackles and roams freely? There’s fear within the desire they elicit, as sexual hunger might well shift into a threat. The horns that puncture will also leave scars. Fohr herself brooded on these topics on the harrowing predecessor -io, a record spawned by the suicide of a close friend and filled with onslaughts of physical anxiety, an album that found me at a difficult time and which I, still, find difficult to listen, with its bipolar hymns of grief between nervous orchestral pop and sinister indie rock being hard to submit to. Where the cover of that record documented Fohr plunging off a tall building, Halo on the Inside returns her underground, confined, an entity within a crooked cage.

The creature that Fohr found within herself this time is marvellous: a libidinal anti-Christ who resides on the radio waves of the 80s, whose sinister presence can be felt in the corners of dance clubs and the sleepless hours after sex. The expressive palette that this resembles is a torn kaleidoscope, somewhere between crooner, industrial, synth, new wave and art rock, part Blackstar, part The Fragile, part Violator, part Secrets of the Beehive. After the muddy emotional quicksand of her previous album, Fohr has found an intoxicating clarity that abandons orchestras for beats. Recorded mostly at night in a basement-studio, the album exudes the limitless, animalistic jungian energy Pan stands for.

The central statement of the record, at least to me, is the nocturnal “Canopy of Eden”: a cross of Hail to the Thief-era Radiohead and Depeche Mode ca. Ultra, Fohr assembles a digital storm of groovy bass and glitching beats, all while announcing: “Fade in to my choral grin / I am a trumpet and I have arrived / I can make a radio / I can make a radio break”. There’s a strength of will, a physical power to the track that was elusive on Fohr’s previous work, a confidence that seems malicious and dominating. This same personality pervades every inch of the album.

The serene organ-led ballad “Cathexis” comes with a collage of voices – distorted and backwards, growling and lusciously whispering – that seemingly depict the promise within submission. With shades of Kate Bush and Tears for Fears, the track’s androgyny feeds into notions of malleability – both of gender and sex, but also of our emotional experiences towards power. The cinematic “Anthem of Me” is its opposite, a haunting industrial rock track with shades of Nine Inch Nails and Chelsea Wolfe. The soundtrack to the bitter court appearance of a cosmic entity, its bludgeoning energy is extremely haunting.

Still, most of Halo on the Inside is incredibly sexy. The opener “Megaloner” channels Dave Gahan’s desperate prayers for salvation over icy synths, promising: “In time, you’ll see me / Through all things dreamy / I can see the face in anything / When the tide pulls to me”. “Truth” goes even further into full dance-territory, with sampled voices, bongo drums and a wonderfully crooked bass, an occult banger in the likes of Bowie’s 1.Outside, joyfully exclaiming the mantra “Truth is just imagination of the mind”, dissolving in ever more rhythmic creations. “Organ Bed” comes as a cyberpunk hymn, all glitches and distant saxophone solo, erupting into an orgasmic finish. The mysterious instrumental closer “It Takes My Pain Away” channels the same sexual energy, ever building until it becomes a blinding drone, all euphoria and no heartbeat. These three final songs almost seem like a sacrificial ritual in themselves.

Yet the most striking composition of the album is the magnificent six minutes of “Skeleton Key”. Opening on an echo of Scott Walker’s “The Electrician”, the song observes the dynamics of seduction, transforming into the gentle sophistication of a David Sylvian song, before, halfway through, it suddenly morphs into a grim, gothic rock onslaught of hammering drums and shrieking metal guitars, with Fohr’s deep voice drowning out any resistance: “Enter the Room of nothing! / Enter the Room of me! / And there: trust me!” It’s an absolutely spellbinding song whose power does not translate well to description. Here, Fohr channels an energy that is beyond the physical realm, a mythical creature outside of time, which might have gone by such names as Pan or Samael or Satan, or simply Man.

It should come as no surprise how much I admire this record. Yes, Fohr has always been a brilliant musician, but she has also been overlooked and marginalised while other figures of the female avant-garde rose to prominence. Much of that might be explained with the subtle, organic energy of her early folk-adjacent albums, which explore femininity through the prism of nature – In Plain Speech and Reaching for Indigo at times sounded like a sonic representation of wild gardens. -io entered the spheres of Scott Walker’s Climate of Hunter, but was emotionally draining and sonically torn between grief and healing. Halo on the Inside abandons those realms for a spectacle of physical force, a pornographic choreography of will and tension. It bids to be danced to, to be submitted to, to be let in through all bodily openings to bleed outwards in pure, black light. Where Reaching for Indigo was inspired by a spiritual experience that left Fohr shaking and vomiting, then Halo on the Inside contains the entity that holds such powers over us. Its name might change, but with its horns and hooves, you will recognise it: let it inside of you!