It may be impossible for Cass McCombs to release a bad album. As a singer with a seemingly natural inclination towards classic melodies and the careful taste to always remain reserved and tender on record, as well as in real life (McCombs reportedly will only grant interviews by traditional mail), McCombs doesn’t open himself up to easy criticism. The downside to this is that he also remains closed-off to overwhelming praise. That being said, his four previous albums have hovered in the space of guarded acclaim (his debut A, 2009’s Catacombs) or reserved disregard (middle albums PREfection and Dropping The Writ). Throughout, the singer has remained workmanlike, always seeming focused on what is next and quickly putting his past work behind him.

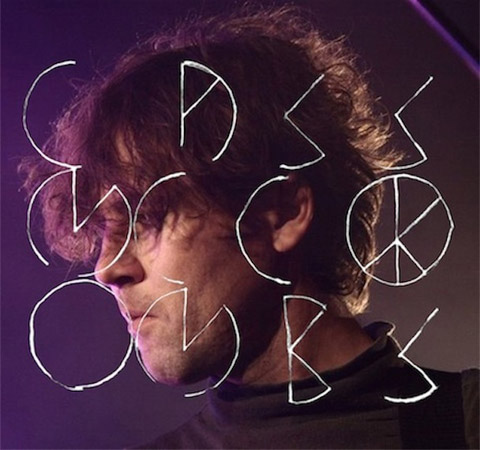

That brings us to WIT’S END, McCombs’ fifth album, the follow-up to the return-to-form album that was Catacombs. Here we find McCombs again retreating from greatness, preferring instead to gallop along at an even pace, without the wow factor of which we know he is capable. WIT’S END ultimately proves frustrating, but equally intriguing, which may be a subtle way of greatness revealing itself.

The closest we get to warmth on the record comes in the opening track and first single, “County Line.” As a singer-songwriter take on a soul song, there is much beauty to be appreciated. The transitional bass line that later becomes “whoa whoa whoa whoa whoa” provides a genuine hook, while McCombs lets his surprisingly strong falsetto reach with the line “I feel so blind, I can’t make out the passing roadsigns.” The extended take on loneliness is lyrically complex, wound in metaphor, and, well, quite lovely.

Loveliness is not something McCombs struggles with. Another meditation on loneliness, aptly named “The Lonely Doll,” strikes a chord through repetition, with McCombs sounding particularly engaging. “Buried Alive” (yeah, this is a cloudy-day affair) slows the album down further with delicate beauty, dragging the listener through McCombs’ pain with a tip-toe melody and gentle refrain of – you guessed it – “buried alive.” And album highlight, “A Knock Upon The Door,” uses barroom percussion and horns that sound like Europe in centuries past. For once, it is the backing band, and not McCombs as a songwriter, that carries the song, allowing the nine-minutes plus number to trudge along smoothly, never feeling like the labor that it should.

And while these high points are all quite good, McCombs never matches his previous high-water marks (“You Saved My Life,” “I Went To The Hospital,” “City Of Brotherly Love,” “Windfall”) and the album is ultimately scarred by its filler. “Saturday Song” doesn’t find McCombs hitting the beach or watching sports. It finds him lonely and hurt, once again. “Memory’s Stain,” is too theatrical for its own good, and too long for our own good. “Pleasant Shadow Song” is completely mistitled. Sure, McCombs is allowed to wallow and deal, and there may be a great many people who find his music more than relatable, perhaps even therapeutic. But the project of WIT’S END is what ultimately throws anyone who is not necessarily ready for eight really sad songs. Humor and cleverness usually make pain easier to swallow and being able to laugh in the face of tragedy is a survival technique for a reason. McCombs would be better served rediscovering wit, rather than abandoning it, thus leaving the listener feeling abandoned as well. But, again, I guess that is the point.