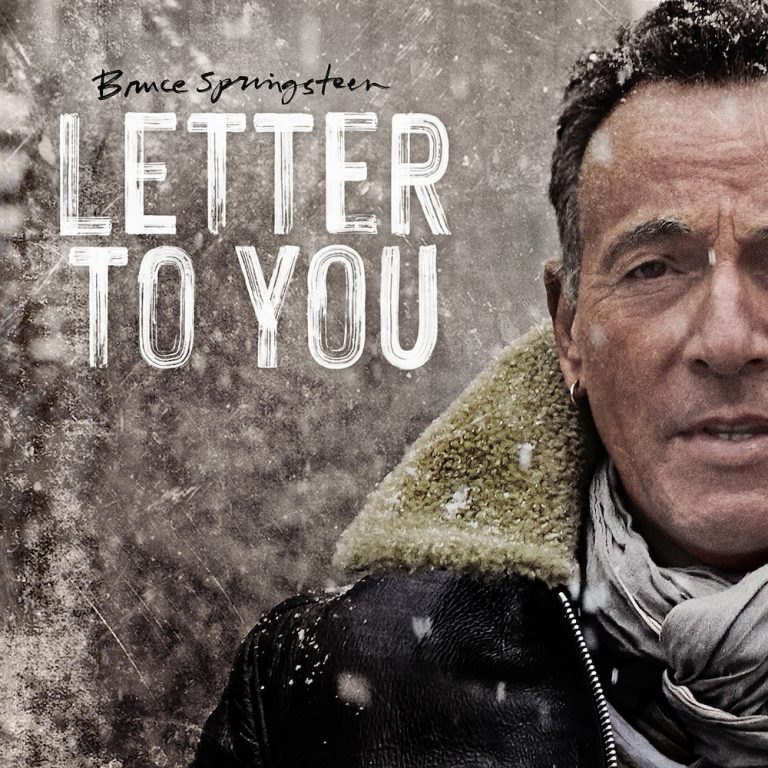

On his 20th studio album, Bruce Springsteen gets the band back together. The album was recorded in just five days with the E Street Band playing live in the studio with no overdubs – something they’ve never previously done. The results are filled with the verve, energy and urgency that his more recent output has been sorely lacking, and although it doesn’t hit the heights of his creative zenith (I mean, c’mon, it’s harsh to judge someone against such ridiculously exuberant peaks as exist in The Boss’s 1970s and early 80s back catalogue) there is still plenty of life left in the old dog just yet.

The power of Letter To You will be familiar to anyone who has seen Springsteen and his band of telepathic musical magicians live – the symbiosis of each player is evident, as is the sheer exuberant joy of creating together. There is nothing new on the album; it plays like a composite of Springsteen’s work to date, with trains aplenty, things on fire here and there, and girls called Mary and Janey to the fore.

Letter To You‘s title track is a paean to lessons learnt and life’s scars worn with a degree of pride. It’s a victory lap for sentiment, graft and honesty in a world increasingly bereft of all of the above. The ‘you’ in the title is multi-layered, too. On one hand, it could quite obviously be a lyricist affirming their belief in authentic communion between artist and audience, though it also feels as though he is singing to himself. A man who took on an array of characters in his songs coming to terms with the fact that they were all elements of his core self – the desire for escape was less about the place and story and more about the personal need to constantly move on, the faces of his song’s heroes etched into the lines on his own face more than was previously evident. It feels like a man looking back and realising that his own life is all there for him to access in his own words – a sweet privilege to possess.

On the album as a whole there is a clear sense of reflection before it’s too late to do anything about it, but not in a self-pitying, maudlin way. The excellent “If I Was the Priest”, which was a track Springsteen played in the offices of Columbia way back in 1972 when auditioning for A&R head honcho John Hammond (but is recorded here for the first time), is testament to this approach. It’s peak new-Dylan period Bruce, when he favoured a streaming flow of lyrics over most other elements of song structure, his lyrics painting immutable images of fully-rounded characters in a way that few others can. It’s a tale of broken people getting by, of dive joints and community and hardship and bootleggers and junkies, all delivered in the breathless style that runs through his early work.

“Janey Needs a Shooter” is the first of the 70s-penned tracks on the record – songs that were played once or twice and then forgotten about in the mists of time when Springsteen’s prodigious writing was in full flow. It’s the sound of a raucous bar band doing what they do best – recounting tales of the downtrodden, the misfits in need of escape and refuge. Here, the lyric centres on a vulnerable girl, with the narrator being a sort of guardian angel figure over numerous predatory men. The first is a doctor who “investigates her and silently baits her sighs / He probes with his fingers / But knows her heart only through his stethoscope.”

“Last Man Standing” is quite devastating for those of us who realise we aren’t as young as we always thought we would be. It’s a reflection of a glorious youth of friendship and brotherhood being over, the song written after the death of George Theiss who left Springsteen as the sole surviving member of The Castiles, the band with whom The Boss honed his skills in the late 60s. The two tracks by The Castiles that appeared on 2016’s Chapter and Verse showed them to be a fierce and fuzzy garage rock band, and Springsteen recounts their camaraderie on “Last Man Standing”, which serves both as homage to those passed and a sense of self reflection by an old man on times long gone. It’s a hard listen to in some ways, mostly because the focus feels so respectful of those dead rather than insufferably self-serving for those still here. The absence of the mercurial geniuses Danny Federeci and Clarence Clemons has somehow never felt so pronounced as on this song. The following track is the only misstep on the record, as “The Power of Prayer” feels like a reprisal of aspects of the tempo and melody of “Last Man Standing” – they could have been separated on the record so their similarities weren’t so stark.

Letter To You may well Springsteen’s best work since 87’s Tunnel of Love. There are dips in quality in places on the record, but there is a general tone of a satisfied human who got out of the rundown places he always sang about to that bright future that was always over the horizon. As nebulous a term as ‘escape’ is, there was always a sense in Springsteen’s spirit that the Cadillac represented the hopes and dreams of a generation of post-suburbanite kids desperate for better than the crushing ennui of chasing the American dream. Only now does he realise that everything he needed was always there in front of him forever – friendship and love.