Traditionally, folktales have been used to pass on wisdom, to create myths that speak to our shared history, to share the odd ditty, and to guard against the dangers of the unknown – even as they are colored by the attitudes of their narrator. The same could well be said for most of Bill Callahan’s albums.

A wordsmith with an ear attuned to the opportunities of surrealism and the occasional bit of anthropomorphism, he writes to share stories which may or may not have any connection to him or any basis in fact. Trying to divine the truth (or the truth as he sees it) of any of his songs is a gargantuan prospect, and is, in all honesty, not the primary reason any of us listen to Bill Callahan. We want the stories to be impressionistic; we do not necessarily want specificity, which is funny, after all, as he goes to great lengths to be as specific as he can regarding the lives of his songs.

These archaic tales speak to our awareness of, and place in, the world around us. As such, they are often influenced by reflections of differing social landscapes, political leanings, and moral vagaries. Going back all the way to Callahan’s official debut album under his Smog moniker, 1990’s Sewn to the Sky, he has offered the same sort of perspectives – nothing so obvious that it could be construed as politicization or proselytization, but in the way he embeds countless echoes of personal events, imagined history, and self-awareness (or lack thereof) into the lo-fi detritus of his music. His albums have always been mirrors, using his occasionally strange and dreamlike imagery and deadpan delivery as a conduit for our own process of emotional and social acclimatization.

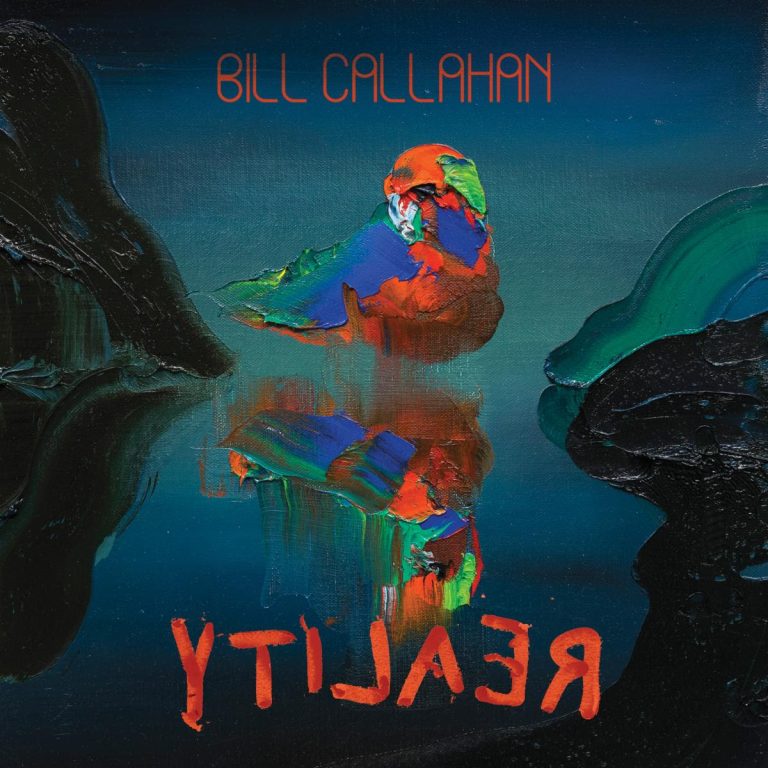

There’s been a lot of talk of maturation concerning his last few records, which makes sense as Callahan turned 56 this past June, but that particular label often leads to a condensing of the perceived emotional range a given artist might express. And with just a cursory listen of his latest album, YTI⅃AƎЯ, any sense of limitation is rightly obliterated. He creates a new collection of myths with this record, an often ferocious and genre-warping look at the terrible and joyous and just strange things which present themselves to us at any given moment. These stories are lensed through in his own inimitable outlook, a mixture of volatile awe, measured anger, crooked mischievousness, and natural wonder.

Opening the album, “First Bird” offers bard-like strums before more modern acoustic rhythms arrive, Callahan’s voice both an observer and active participate in this shuffling dream-state: “And we’re coming out of dreams / as we’re coming back to dreams.” It all comes back to dreams, those of a nocturnal kind and those which we strive to achieve all our lives – and from these first lines, YTI⅃AƎЯ shows us how these stories will relate to us, how their histories will grow in stature and legend. He has always asked us questions, had us attempt some sort of reconciliation between his words and our experiences, but here, he confirms that things are on far shakier, non-physical, ground. What is ‘reality’, and how sustainable are our own perspectives in the face of such tenuous circumstances?

With each song, we are introduced to the characters and then to the environments, all garbed in Callahan’s usual bucolic clothing, though moments where synths, brass, and clarinet are heard lend these tracks a more engaging visage than might have been presented in the past. “We warmed our hands in the corpse of a wild horse“ goes “Everyway”, proving that he still has a hypnotic flair for details both gruesome and gorgeous. The notes from his guitar ramble and tumble between vocal harmonies and odd rhythmic flourishes. His penchant for dark humor arises as he sings “we’re all in this horse together”, another welcome reminder that this is still the same Bill Callahan who once instructed his wife to “dress sexy at my funeral”. Allegories abound while he flirts with anthropomorphizing life itself as we tuck our cold hands into its belly.

He takes a turn toward absurdism with “Bowevil”, a slow burning stomp that turns the titular beetle into the herald of the apocalypse, or some other nameless devastation. It’s a dense and foreboding song that makes us question the true identity of the insect. But like most of his songs, the meaning isn’t laid out with any clear indication – are we the bug or are we the nameless antagonist lamenting its presence? Additionally, “boll weevil” was a term used to describe conservative Democrats in the mid-to-late-20th century. Is Callahan playing around with some veiled political rhetoric here? The answer isn’t forthcoming, and so we continue to parse out meaning as we can, leaning into our own lives for understanding.

On “Partition”, he sing of “big pigs in a pile of shit and bones” and to ”meditate, ventilate, do what you gotta do / You do what you’ve gotta do”. What defenses have we erected to keep the terribleness of the world at bay? This track scans as a cautionary fable for people who’ve yet to adapt to the twisting configurations of reality. Organ lines run and stumble through bounding jazzy percussion; the thumping bass acts as a repetitive heartbeat keeping track of time. “Lily” is a story of mortality and familial connection, echoing with tender memories and longing. At times, you can hear what sounds like the creak and shudder of floorboards. His voice feels uncomfortably close, as if we were intruding on some private moment meant only for him. Scraps of electric guitar tumble around as austere notes are plucked on an acoustic guitar. It possesses the distinct feeling of a wake, a tribute to the dead and to their impact on our lives.

We return to the natural world on “Coyotes”, a gently rollicking tale of love held together through small and significant moments. “They say never wake a dreamer / maybe that’s how we die / I realize now that dreams are real” he reveals, further connecting our subconscious with tectonic emotional revelation. There are angular structures here, the slight serration of electric guitar, a harder edge to a few words, but the impact is lessened by the occasional patch of gossamer piano. Here he drops his guard and simply admits: “that is how and why I love you / And have always and will always / Love you now”. It is a beautiful admission, and one made all the more resonant through its plainspoken intimacy.

Sometimes you just need to look around and consider your surroundings, even if they are over 100,000,000 miles away. He advises us to do just that on “Planets”, a soft and sometimes dissonant exploration of self and terrestrial inconsequence, featuring synths, clarinet, and visions of celestial objects “Singing as they spin / Big and Hawaiian”.

Album closer “Last One at the Party” holds one of the album’s greatest lines: “Eyes like typewriters held all the poetry you’ll ever know”. The track doles out a sauntering bit of guitar that curls tightly around his voice, offering a story of social misfortune and obliviousness. Is Callahan talking about himself here, wondering if it’s time for him to leave the stage? Has he stayed too long – are people just counting the minutes until his voice fades away? He may be dealing with some existential crises, but the song – and YTI⅃AƎЯ as a whole – suggests that he only just begun to gain a measure of understanding of the world and his own personal involvement in its myriad complications.

YTI⅃AƎЯ finds Callahan at his most personally enigmatic, taking inspiration from his own life and filtering those experiences through a prism of modern folktales. He offers us all the most enticing details but manages to keep it wonderfully vague at the same time, a treasure trove of musical obscurantism. But these are the important things in his life, whether factual or not, whether deserving of remembrance or not. By approaching these topics through this particular framework, he’s able to give an account of inexplicable things and possibly pass on a word or two of wisdom. And maybe, somewhere in here, he just wanted to share a few new songs. Whatever the initial intent, these songs now live on as The New Fables of Bill Callahan, and let’s just hope he doesn’t keep us waiting too long for the next volume.