More than a decade into releasing music under his own name, Ben Chatwin is unquestionably making the exact kind of content he wants to make. The Scottish experimental electronic musician and producer hones their skill with each release, managing to find new ways to make the alien sound even more otherworldly. His source material and inspiration may be organic (a one hundred-year-old Dulcitone on the H.G. Wells-inspired The Sleeper Awakes, string quartets on Drone Signals and Staccato Signals, the 50Hz hum of the power grid on 2020’s The Hum) but Chatwin has a fascinating way of channelling whatever the original source material is through all manner of synths, pedals and hardware to make electronic drone music that sound both excavated from the bowels of the Earth’s core and beamed in from planets light years away.

On Chatwin’s latest album, Verdigris, the process remains much the same on paper. Pondering spirituality in the digital age, this time Chatwin found inspiration from medieval choral samples, morphing and warping them until unrecognisable. Go looking for them here and you’d be hard pressed to find much you can point to as a discernible set of vocal cords. “Chorale”, with its echoes and washed out looped samples of what sounds like backtracked voices, is perhaps the only example where you might find something recognisable, but even then the track sounds more akin to some gargantuan vehicle burrowing through terra firma or the static of a tapped phone receiver. It’s Chatwin doing what he does best, making the comprehensible unrecognisable.

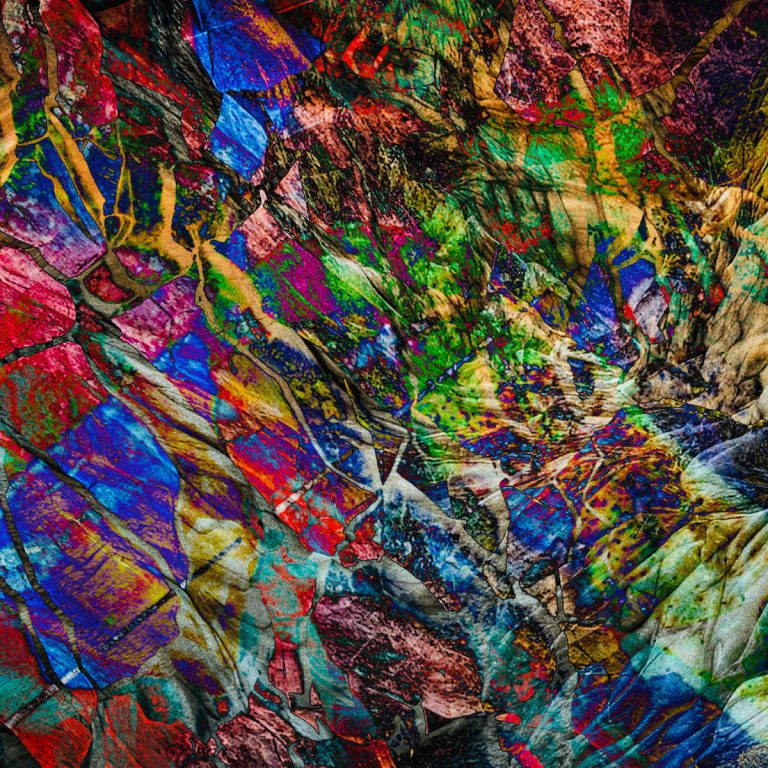

With drum machines that flicker like frayed wires and synths that reverberate like some abandoned factory in a dystopian movie, Verdigris is perhaps Chatwin’s most industrial and metallic record to date. (It’s fitting that the album title refers to that aqua coloured encrustation or patina formed on copper or brass by atmospheric oxidation.) On “Petroglyphs” something of an EDM beat and groove emerges, only to be swallowed by the tar-like synths as the track evolves layers and layers, consuming the rhythmic momentum in the process. “Dolmen” and “Sawtooth” could easily be excerpts from a full sci-fi movie soundtrack, conjuring eerie, doleful landscapes that have an alien-like quality to them. (Frankly it’s surprising Chatwin hasn’t been headhunted to score large scale film projects.)

Where the album lags a bit is when Chatwin doesn’t quite manage to sustain a track’s theme over an extended period. “Pig Iron” has all the supernatural qualities of much of anything else here, but across six and a half minutes the sense of foreboding wanes here and there. Similarly, “Ecology of Fear” paints an image of sullen, lonesome wandering and presents a lighter tone and texture across its five minutes, but it also does feel a little like incidental music for a video game’s menu screen. Moments like these do mean that Verdigris dwindles a little at points, but for both new and seasoned fans, the overall quality of the sound and its ability to invoke images and sullen scenery stays pretty consistent across the album’s 37 minute runtime.

And when Verdigris is working at its best, it’s Chatwin firing on all cylinders, making gothic electronic music that galvanises, grinds, and gores. Opening track “Collapsing in Feedback” is like some behemoth of a creature coming back to life, distorted guitar riffs and waves of fuzzy synths staining like ink; like the title suggests, it’s easy to imagine Chatwin trying to control an oncoming flood of feedback by plugging channels at each turn. At the other end of the record more lightness comes through, the warped, flickering tones of “Elegy For All We Lost” unspooling like reels of tape. It’s peaceful and is a juxtaposing white light against the rest of the album’s tenebrific countenance. One could even interpret it as those choral voices transcending to the heavens above. This realm or another, Chatwin still deals in otherworldly qualities.