Reality has degraded into a bizarre psychedelic rainbow of untruths and faded blood stains! When on “Laraaji” – the opening track of Armand Hammer and The Alchemist‘s new album Mercy – billy woods raps “Should’ve killed me when you had the chance, now it’s out your hands / I don’t need an advancе, I don’t dance / Herzog voiceovеr, the camera pans / Everybody’s a cameraman”, I zoned out.

The images in my head became blurred waves: countless images of Gaza collected by young journalists who were declared terrorists and butchered by western paid bombs; the triple angles of a political pundit being shot in the neck, red blood gushing out; the AI edits of a leftist streamer being electro-shocked by his dog; modern minstrel shows of people eating exotic plants and animals; YouTube influencers whitewashing mass slaughter, baring shark teeth; computer-generated pets absurdly violating each other, foreign languages barked on top of their digital tears. The camera has morphed from a documentary feature to an ideological compass of the world: there never was a shock collar, it always was a genocide, we have never abandoned the xenophobic patronage on foreign culture, we still crave blood: blood: blood. Facebook from hell is just Facebook now.

The last time that ELUCID and woods got together, they released a cryptography of Unheimlichkeit. Their occult, haunted and endlessly layered We Buy Diabetic Test Strips was a monumental achievement. Using echoing themes and dream-like imagery over diffuse beats, it chronicled an American unconscious that anticipated the horror film the future – our present – would become (was woods’ line “I read the paper even though they tell me not to” a reference to Early Edition?). This intrusive paranoia might have come from the uniquely Black understanding that every political disaster – every genocide, every fascist government, every capitalist reframing of social rights into marketing ploy – is the consecutive outcome of a colonialist mindset that has shifted from foreign shores to the streets and suburbs of modern national infrastructure. No matter who supplies the bombs and bullets, they still slaughter millions. On Test Strips, the threat were ghosts and shadows – on Mercy, things have become more tangible, but all the more diffused.

That might be part of the DNA this project contains. It’s their second full collaboration with producer The Alchemist since the standout (dare I say: modern classic?) Haram, and comes with the ballast of the LA native being put on blast for his Zionist tendencies over the past couple of months. But then it’s also important to point out that Alc has decried fake news and called for Palestine’s liberation as recently as this September. On the more positive side, it also follows a string of releases which might well be the best in recent hip hop, coming off ELUCID’s incredibly abstract and poignant standouts Revelator and Interference Pattern, and billy woods’ flawless run since at least the start of this decade, if not earlier. The duo is operating on such a high standard at this point, it seems almost absurd to try and contain their far-reaching and often elusive references and crossover storytelling techniques in a single project’s review. Yet for the first time, there’s an apparent reflection of the inability to speak.

This rumination comes in woods’ verse on “Dogeared”, when he is confronted by a woman about his role within the world: “She finished her drink and looked at me inquisitively, asking / ‘What’s the role of a poet in times in like these?’ / I never answered, but it stuck with me all week”. The track becomes a chronicle of woods’ movements of the next couple days – organising a tour, taking care of the kids, the daily chores. The lines come clear as daylight, and finally rest with woods seemingly observing his son leaping “into puddles with both feet on the way home”. By the end of the week, he returns empty handed: “She said, ‘You got an answer for me yet?’ / I said, ‘I’m still grappling’”. That verse stands out – especially in contrast to ELUCID’s foggy part on the track (“The patterns never more apparent, blaring / Peace scatters after death strokes, next notes / Sour to the tongue, alive with pleasure / Kelly green and mandarin orange / Who I’m is? Who I’m aren’t? / Everything justified when you starving, right?”).

The message becomes clear later: woods isn’t speechless because he lacks meaning as a poet, but because the reality has shrivelled into what he deems “a dollhouse of horrors”. On “u know my body”, over icy piano notes, he raps about the genocide with brutal clarity: “Bodies in the water like apples bobbing gently / Bodies stand sentry on battered corners gently / With the tiny coffins almost barely empty / Bodies on bodies on bodies on bodies on bodies…”

This shift of reality might also be why the album lacks the gentle dub that lifted Haram from the gutters. There’s no perceived tonal optimism here, such as on “Black Sunlight”, “Falling out the Sky” or “Squeegee” – and also no libidinal destruction fantasy as the cannibal vampire of “Stonefruit”. In its place is the labyrinthine movements ELUCID tracks on “Crisis Phone”: “Twenty years came and went / My face on posters plastered with the ghost of ghetto past / Pour out a little liquor, date smudged on eviction notice, if you notice / X you out the picture, not the record / One for good measure, two for getting over, closure”. “Moonbow” goes as far as imagining a cyclical movement of destruction that could be as well about New York as it is about Gaza: “Who promised you tomorrow when they came for me? / We was watching towers rise where they fell / Rockets, comets, scarabs, and scales / What matters, whose body?” The pessimistic, acidic and wintery “No Grabba” laments the self-destructive tendencies within the black community (referencing woods’ “Born Alone” off Golliwog) and hopelessness of struggle – especially with its final sample: “Like, did you really think we’re gonna win in the beginning? / Thought I had a fighting chance, but it’s a little different in person.”

There are two standouts of neon-lit bliss: the closer “Super Nintendo”, with its Moog synth sample and the rappers recollecting their fading youth. woods’ verses here especially are an emotional gut punch as he speaks of his mother slowly drifting into old age (“Mom’s half deaf, still sharp but starting to forget / Repeating herself, retracing our steps / Used to be up late pacing, now she sleep like the dead / I passed out on the couch, dreams like lead”) and he recounts the naive bliss of a different era: “We had a time, don’t let ’em say different / We was drunk and high watching Intervention / We was just happy to be outside when our peoples was in prisons of all types / We was just livin’”. Focusing on those mother figures slowly dissipating and their bodies tiring (ELUCID’s lines imagines them as cosmic beings that interconnect with his receding hairline: “Of course she grabs hair that grows towards heaven / Pleasure in possession, melding / Black hole she fell in / Well then, every other year, I’m shedding”), the two find a way to ruminate on to what degree Black struggle is something age conveys gradually, rather than just throws individuals into – to what degree the innocence of being hopeful and without guilt makes way for the confession of being confined in mortality, which in turn is all the more brutal if you’re considered marginal within the larger makeup of a nation by those in power. “We had fun on that Super Nintendo / Sunday services, blew church out the window / We was done, finger guns to our temples” – the games of kids morph, with time, into the foreboding realities, as the outside imagery of Black men in prisons and the loss of the older generations slowly trickle in from the outside.

The other lighter track is the beautiful and jazzy “Calypso Gene”, where the two rappers use the image of water to ruminate on ancestry (“I used to hustle with your grandmother / Used to party ‘fore you was even thumb-suckin’ / She lived out the sticks where you could get ’em by the dozens / Get ’em off like nothin’/ Used to let me hold the door keys”), fate (“Snipers watch me swim, two-point-seven pounds of pressure on that trigger / Gaugin’ the wind through narrow eyes / Three sisters over the cauldron”) and the strange foreboding sense of finality (“The water gentle, the water deep / Nobody speaks, certain things you just know in a dream / The hum of the engine, the thrum of the seat / Father lift me out the car, half-dead / Carry me in to sleep”).

But darkness continues to seep in – with “Nil by Mouth”, where consumption and cannibalism become one, and “Moonbow”, where tyrants orchestrate international movement, just waiting in the wings.

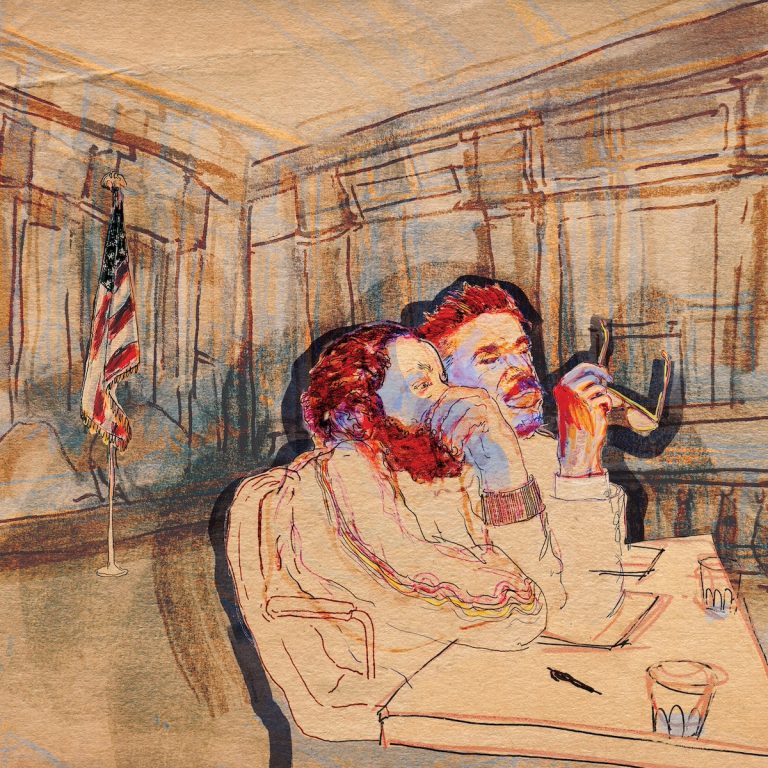

For long stretches, if it comes to listenability, Mercy could stand as Armand Hammer’s best album. The dynamics of the faster cuts, such as “Longjohns”, is immaculate and punchy. The quiet, sinister tracks strike with a nocturnal violence that is accentuated by stretched piano notes or futuristic, Carpenter-esque synthesiser waves. The images of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver seem inevitable: a haunted lunatic, stalking the streets of New York City for prey. ELUCID’s collage work, inspired by a documentary of Brooklyn youth creating in a museum, is echoing and foreboding, giving the tracks a cavernous tone: images being projected onto underground walls, deformed and barely visible, chasing down tunnels, reverberating. And on top of that, the flows of woods and ELUCID are absolutely immaculate, with their intersecting parts on “California Games” and the rapid fire deliveries on “Laraaji” arguably being the standout.

But the most intrusive question about the album remains how it holds up within the shadow of the second Trump regime: how it reflects on the growing fascism that, in fact, seems to permeate most nations. That is where the record unfolds: Mercy still observes the structural identity crisis of Blackness – the lasting poverty, the loosening ties to an ancestry struggling with (and barely surviving) trauma, the self-destructive urges within systems that ignore historical pain. But often, it takes a step back to portray a larger evil that seems to no longer discriminate so much as it just feeds off human souls.

Over the course of his last couple of albums, woods has introduced this floating apparition of feminine libidinal phantasmagoria: part werewolf, part vampire, part cannibal, part spectre, part succubus, suddenly appearing in the middle of the night, draining him. On Test Strips, there was already a shift towards odd masses of cannibalistic zombies, who seemed to merge into a mindless force that flooded streets and online spaces. Now, their spirit and purpose seems to have infected most of society. The tranquility of air travel woods chronicled on Maps is gone, becoming Pinochet’s night flights. Partners morph into mass murderers and the masses into marauders. The dead are just piles, like bricks, to be fashioned into new towers, which, in turn, are torn down by bloody hands. While their kids innocently jump in puddles, their socks protected by resilient shoes, the two rappers swim in the Hudson, the fates already conspiring against them, all while their mothers slowly fade away. The symbolism of this album, poetic and interconnected, is vital and immense, while the sonic background is (for the most part) disquieting and unnerving. More so than Haram and even the spectral Test Strips, Mercy captures a world that is slowly embracing the unbearable evil of switching channels that morph to dead static.