Stephin Merritt has forged a career balancing precocious wit with pop theatricality. As the frontman for The Magnetic Fields for more than 30 years, he’s had plenty of opportunities to run roughshod over genres, accumulating and adapting tousled sounds and experiences into a brew of wickedly bitter recollections and dryly humorous observations. His songs seem poised upon a precipice of vulnerability and devastation, waiting for some capricious impulse to decide whether to embrace the darkness or just go home and have a beer.

His records have long acted as emotional sketchbooks in which he confronts – and evades – the difficulties that block his way forward on any given day. They’re also a means for him to expose the things which bring some measure of light and lightness into our dull grey world. In The Magnetic Fields’ music, fleeting thoughts become grand pop ballads, while heartbreaking epiphanies are built up through a truly euphoric pop simplicity. Merritt and his regular cadre of musical accomplices, including Sam Davol, Claudia Gonson, Shirley Simms, and John Woo, treat pop music less like a passive genre and more like an ever-shifting rhythmic perception that adapts itself to the whims of its handlers.

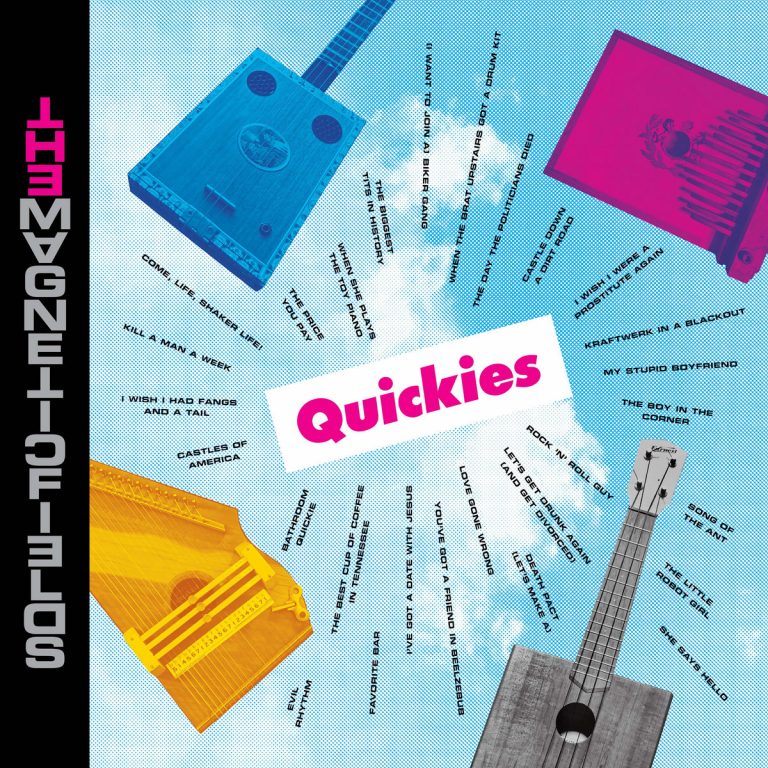

Throughout their new release, Quickies, Merritt and the band continue this emotional note taking, basking in melodic brevity and the draw of pop’s innate malleability. Over the course of 28 tracks – ranging in length from 12 seconds to roughly two-and-a-half minutes – he comments on the usual topics, though he does branch out and sprinkle in some quips about Kraftwerk, robots, tits, and ants across the various landscapes of the album. Inspired by his affection for the short fiction of Lydia Davis and his work on a book of Scrabble Poetry, Quickies is purposefully compact in its design but doesn’t often feel rushed.

We’re quickly invited into this travelogue of song through the opening 29-second track “Castles of America”, a jaunty tune that plays into our expectations while also leaving us wanting. It’s one of the few ultra-brief songs that lingers in your head past its short runtime. And honestly, if there is one critique to Merritt’s conceptual strategy here, it’s that even with his inimitable wit and peerless lyricism, there’s only so much you can do in the span of 17 seconds (as on “Death Pact (Let’s Make A)”) before you’re forced to concede that pop music does need at least a little space to evolve and bloom into something worthy of our attention. These micro tracks seem more like a simple novelty and don’t necessarily foster a creative atmosphere where Merritt’s words and the band’s plucky arrangements can be highlighted as they should be.

Those few tracks aside, there are acres to adore here, with tracks like “Let’s Get Drunk Again (And Get Divorced)” and “Evil Rhythm” developing their own unique perspectives and moods. “The Biggest Tits in History” is a smirking come-on that isn’t actually about what you think it is, while “The Best Cup of Coffee in Tennessee” is a minimalist wonder of strums and curious melodies.

Quickies is an album that revels in double entendre and wordy subversion, and Merritt luxuriates in each fleeting syllable and rhyme. Especially memorable are “When She Plays the Toy Piano” and “I’ve Got a Date with Jesus”, with their intricate pop blisses and skeletal frames. But as minimal as many of these songs are, they also sound lush and invigorating. The band has always been able to confound with their ability to simultaneously break a song down to its base elements while also developing a considerable emotional density during that same deconstruction. Moments that should feel translucent and airy possess a weighted presence and force belying their superficial softness.

Over the span of 28 tracks, you can expect some filler, even from a band as ambitious (and consistent) as The Magnetic Fields – and that is the case here, although the brief lapses in quality are softened by the virtuosic movements which surround them. Quickies may not reach the spectacular operatics of 69 Love Songs or the spacious coherence of 50 Song Memoir, but it doesn’t need to; this is a record unanchored by the lofty expectations of previous releases. It’s a series of notes and remembrances, fond and mournful and often whimsical in nature, which provides ample evidence that the band still hasn’t fully excavated all the mysterious beauty that pop music has to offer.