Country music has had many musicians who inhabit the spirit of the songs that they sing, but Loretta Lynn’s life was a country song – it needed no elaborate embellishment. Born in Butcher Hollow, Kentucky in 1932, Loretta Lynn (then Loretta Webb) was the oldest daughter and second child to Clara Marie and Melvin Theodore Webb. Her father was a coal miner and a farmer and would pass away from a stroke when she was 27. But his presence and the hard-working habits he passed on to her would spark a great internal need to succeed and a desire to view daily struggles as opportunities for growth and personal development. God help the person who thought to get in her way.

She married Oliver Vanetta “Doolittle” Lynn in 1948 when she was only 15, and their marriage would last until he died in 1996. In those early years, they faced problems as any young couple does, and these toils would inspire many of her songs in later years. But it all really started in 1953 when “Doo” bought her a $17 Harmony guitar. She taught herself to play and founded Loretta and the Trailblazers, which included her brother Jay Lee on lead guitar. She released her debut single, “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl”, in February of 1960 on Zero Records. It rose to number 14 on the Billboard country charts after weeks of driving from one radio station to the next to promote it. But this initial success was just the first step in what would go on to be a career spanning over 60 years.

On October 4, Loretta Lynn passed away at her home in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. She left behind a legacy documented on over 50 studio albums, live recordings, and greatest hits collections. Her voice possessed all manner of rebellious intonations and intentions, a firebrand for country music in a time when women were, with very few exceptions, left to remain in the shadow of their male peers. Loretta was different – you could already hear it in her 1963 debut album, Loretta Lynn Sings, where she was already writing and recording a few of her own songs and discovering what it meant to be Loretta Lynn. Those songs were fiery and held tight to her own sense of identity, that of a coal miner’s daughter and native Kentuckian, and were born from a sincere desire to leave her own unique imprint on the genre.

Whether she was singing about women’s rights – though she never considered herself a feminist – or was simply calling out men for the terrible ways in which they treated their women, she developed her own sense of lyrical activism that bridged her more conservative upbringing with the shifting tides of social change throughout her career. She never recorded songs to intentionally buck the status quo; it was all just common sense to her. Contraception, the stigma of sexual gratification, and marital boundaries were all topics that appeared in her songs, left-of-center topics to be sure for a genre not well-known for its progressive history at that time. But Lynn was simply speaking from the heart and holding the appropriate feet to the fire when she felt the world trying to rein her in.

When digging through the vast treasury of her discography, it might be hard to get a sense of where to begin for someone unacquainted with her extensive output – or honestly, for someone who might be familiar with her work. From Christmas albums to twangy ‘80s adaptations to more recent rockier and folky albums, her music captured so many moods and themes that her creativity seemed to never rest. Below you’ll find a list of 12 albums that encapsulate Lynn’s aesthetic, both lyrically and sonically, and provide irrefutable evidence that she was one of country music’s most rebellious storytellers.

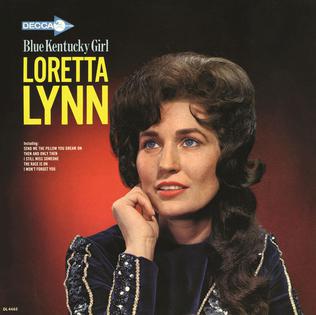

Blue Kentucky Girl

(Decca; 1965)

Even this early, there were signs that Lynn would break free of the mold that country music as an institution seemed to impose upon its female artists. There was a clarion quality to her voice, a determination that couldn’t be suppressed. She effortlessly wove her way through the galloping rambles and twangy guitar passages. The title track is one of her most well-known songs and is an ode to simple living and familial ties, themes which would echo throughout her albums for decades. Her cover of Johnny Cash’s “I Sill Miss Someone” is buoyed by her soaring vocals and shivering steel guitar, and it exemplifies Lynn’s ability to adapt other people’s words and music to suit her own needs and desires. She was a musical chameleon and could easily slide into any situation and elevate every aspect until it was thoroughly her own.

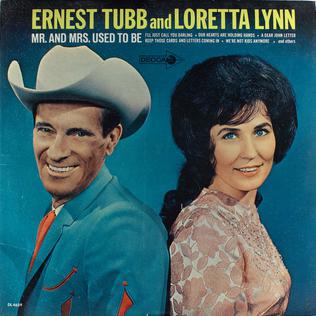

Mr. and Mrs. Used to Be (with Ernest Tubb)

Mr. and Mrs. Used to Be (with Ernest Tubb)

(Decca; 1965)

Before she found considerable success duetting with Conway Twitty on subsequent records, she delivered a handful of collaborations with country icon Ernest Tubb. Mr. and Mrs. Used to Be was filled with stories of failed romance, longing, and growing past youthful infatuation, all brokered by her sweetly framed voice and his supporting baritone. These songs were enlivened by the guitar work of Buddy Charleton, quivering and resisting corporeal form as the notes threaded between Lynn and Tubb. “I Reached for the Wine” recalls the details of a failing relationship while “Our Hearts are Holding Hands” recalls the struggles and passions of a long-distance affection. As soon as you embrace the plainspoken thoughts here, made with conviction and without irony, the emotional complexity of this album grows until it becomes a full-fledged country wonder.

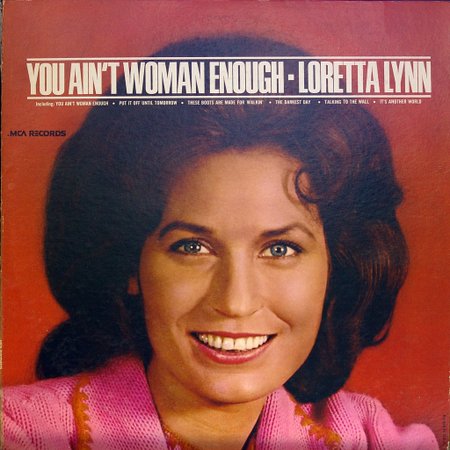

You Ain’t Woman Enough

You Ain’t Woman Enough

(Decca; 1966)

Loretta Lynn was never so fierce as she was when telling other women to keep their hands off of her man. Sure, it plays into a deep country music stereotype, and didn’t help to alleviate the “catty women” archetype inherent to the genre, but Lynn sang with such conviction that her characters became fully fleshed-out individuals, fighting for their own happiness, which also just happened to include the love of a man. On the title track she sings: “Women like you / they’re a dime a dozen / you can buy ’em anywhere” — a pretty forceful middle finger to anyone who thinks they can rob her of the love she holds so dear. But she is ready to admit that sometimes love isn’t enough, and on “Someone Before Me”, she faces the heartache of knowing that her partner is still in love with his ex. There are silver linings and happy endings, but Lynn isn’t naïve enough to think that romance can fix all the problems in a relationship, as these songs so intimately reveal.

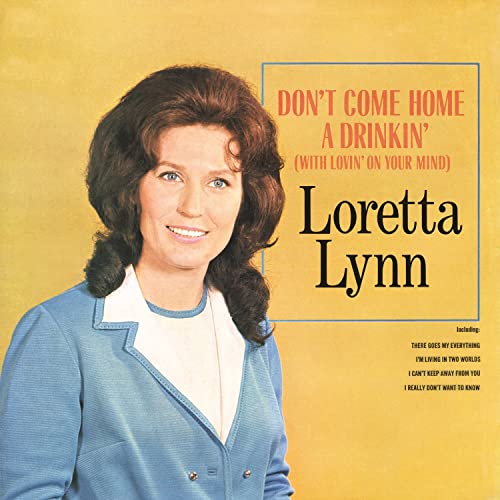

Don’t Come Home a Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)

Don’t Come Home a Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)

(Decca; 1967)

As her career progressed, Lynn developed a reputation as a woman who took no shit from anyone and would call them out for any slight she perceived. Don’t Come Home a Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind), both the album and its stellar title track, was a watershed moment in how people viewed her, as they realizing that she was ready to give her heart away but also cautious in how that process happened. There’s was a subtlety to the album that was missed by many people — it wasn’t just some jokey late night proselytization. She was saying that she might actually be fine with whatever he had in mind but that it was up to her to decide if he received the warmth of her bed. Small moments like this, deeper meanings enshrined in classic country couture, were what set her apart from the mass of country singers whose seeming emotional depths revealed only stagnant superficiality.

Written by Lynn, the title track to Fist City peaked at No. 1 on the US Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, with the album eventually becoming one of her most beloved albums. The lyrics may seem a little cornball now: “I’m here to tell you, gal, to lay off of my man / if you don’t want to go to fist city”. But again, Lynn’s presentation, both passionate and self-confident, allows us to see the beating heart behind its bravado. She also tackles country classic “A Satisfied Mind”, creating a worthy adaptation to stand alongside some its finest interpreters. On the closing track, “What Kind of Girl (Do You Think I Am?), she places her own dignity and well-being above that of someone who’s finally shown their true colors and tells them to get out of her life — “if that’s what you want / take me out of your plans”. She’s not going to suffer fools lightly and prioritizes her own physical and mental health above that of anyone thoughtless enough to try to shame her into doing something she doesn’t want to do.

Coal Miner’s Daughter

Coal Miner’s Daughter

(Decca; 1971)

After almost a decade of albums, Lynn was already considered the Queen of Country Music, but Coal Miner’s Daughter launched her status as country music royalty further than even she thought possible. The title track is one of the most enduring classics of country music and finds Lynn detailing in harrowing detail the struggles she faced in her youth; it’s focused in on the nuances of her voice as heartache, joy, and themes of family connection are explored and blown out into cinematic proportions. And while a good part of the album is dedicated to covers, she never loses her signature sound in the words and music of these other artists. Tackling songs from Kris Kristofferson, Glen Campbell, Marty Robbins, Conway Twitty, and others, she creates a new slate of country standards. She was able to take simple expressions of love and affection and turn them into complex narratives that spoke to the value of her humble beginnings and to where she might find herself a little further down the road.

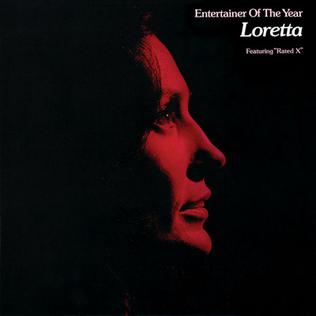

Entertainer of the Year

Entertainer of the Year

(MCA; 1973)

Apart from the chart-topping single “Rated X”, a daring and unconventional (at least for country music) look at divorce and the good and bad that can come from it, Entertainer of the Year had no other singles released, usually a sign that the bulk of it was somewhat forgettable. But digging into the album now, it’s easy to see just how complex this one was for Lynn, with its bluesy overtones and lyrical repudiations of various social stigmas. “Hanky Panky Woman” is a blues number dressed up in twangy garb while “Possessions” details the evolving disillusionment with someone who’s come to value possessions over love. This album was one of her more intensely introspective albums, one that seemed to speak to her own concerns about the world and our own mortal conditions. Darker thematically, Lynn was exorcising and embracing some perceived demons here, and Entertainer of the Year provided substantial evidence that she excelled at both.

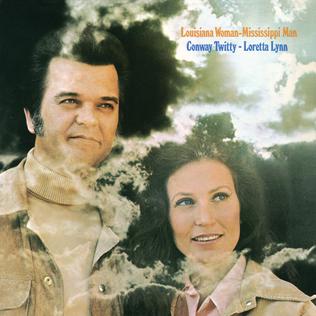

Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man (with Conway Twitty)

Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man (with Conway Twitty)

(MCA; 1973)

Their third collaborative album together, Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man, marks a high point in their history of duets. Anchored by the enormously successful title track, the album is awash in clever arrangements and vocal interplay, with both artists finding new ways to explore the depths of their collective creativities. And while there might be some expectation of homogeny here, given the nature of the record, Lynn and Twitty are really firing on all cylinders, making these song hums with an unmatched energy. Highlights include the honky-tonk romp “Bye Bye, Love” and the sparkling country rhythms on “What Are We Gonna Do About Us”, with each track feeling more like personal conversations than anything else. They’ve been talking for hours; we just happened to catch them at the good parts of the story.

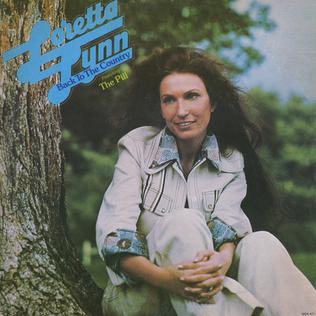

Back to the Country

Back to the Country

(MCA; 1975)

Thought its sentiments may be rather roughly drawn, “The Pill” returns Lynn to controversy as she lauds the freedom which birth control affords her. As the lone single from Back to the Country (her biggest selling record of the ’70s), the song was met with radio censorship, protests, and outright banning. But it’s not just a treatise on female bodily autonomy; it’s also a repudiation of the way in which men would often control women through pregnancy. She realizes that he can go out and do whatever he wants without consequence, but she must stay home with the kids and tend to their needs. She isn’t knocking motherhood by any means, just the way some use it as a way to deny certain freedoms to others. Other songs like “Paper Roses”, with its understanding of false affection, and the openhearted “Will You Be There”, use shuffling rhythms and crystalline melodies to examine those feelings that echo so strongly in our hearts.

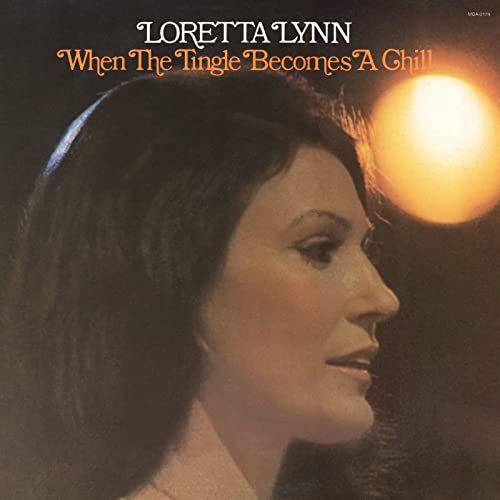

When the Tingle Becomes a Chill

When the Tingle Becomes a Chill

(MCA; 1976)

Love has always been one of the greatest motivating factors in Loretta Lynn’s music, a central theme around which she navigates the tumultuous peaks and valleys that wind themselves into the inner reaches of her heart. When the Tingle Becomes a Chill takes this core idea and lays out the ways in which it affects us every day. There are moments of elation, fear, and despair here, but in the end, love is there for the taking — we only need to realize that it holds the capacity for both happiness and grief. Fading love is highlighted on the countrypolitan ramble of the title track while “Leaning on Your Love” is all about codependency (good and bad) that develops in a particularly strong relationship. On “All I Want from You (Is Away)”, she remembers the fond times but also realizes that her needs and desires have grown beyond the capabilities of the man she loves. She reminds us that when it time to walk away, there’s no reason to forget about either the good or bad times as both guide us in the years to come.

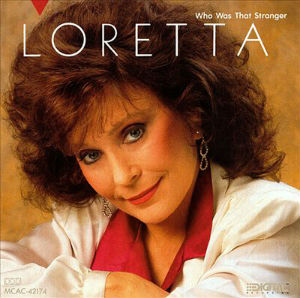

Who Was That Stranger

Who Was That Stranger

(MCA; 1988)

Country music in the late ’80s was marked by a more fleshed-out sound, more dynamism in its framework and a focus on pop-centric melodies. On Who Was That Stranger, Lynn embraced these aesthetic shifts and released what is arguably her best of the decade. She continued to position herself in and out of love, with twangy guitars and glistening piano shivering around her graceful voice. Swatches of harmonica are heard as are fiddles, with all these elements combining to fashion a broader statement on the viability of the genre in a decade so ostensibly obsessed with corporate marketing ploys and manufactured superstars. Looking back, it’s funny how easier you can trace the empowering messaging of “Survivor” here to the pop-driven feminist themes of Destiny’s Child’s song of the same name some two decades later. These ideas are all cyclical — Lynn made them her own back in the 60s and 70s and continued to rework them into ideas that spoke to a new generation of listeners.

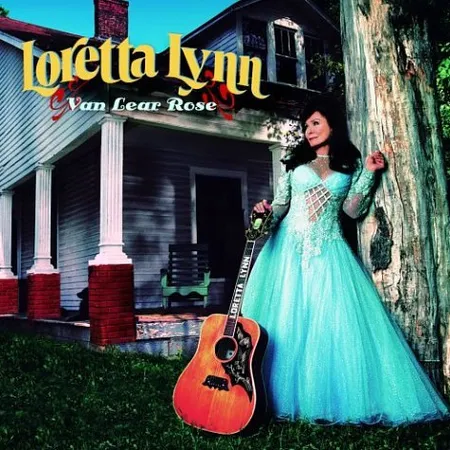

Van Lear Rose

Van Lear Rose

(Interscope; 2004)

Loretta Lynn was always a socially conscious hell-raiser, and though she always maintained a core connection to a more conservative way of life, that didn’t mean she couldn’t bridge those two viewpoints and make herself a fiery spokesperson for both progress and the safety of nostalgia. Van Lear Rose, produced Jack White, was her way of connecting with her past while also discovering what that past could mean for her future. What was initially envisioned as an attempt to connect the contrasting styles of Lynn and White became something much larger than either could have anticipated. Released to universal acclaim, the album was filled with poignant familial callbacks, raucous barnburners, and a voice unmatched in sincerity and emotional wallop. They brought out the best in each other, delivering an album that could hit with the force of two tons of dynamite but would also bring you to tears at a moment’s notice. It was lighting in a bottle; it was a rejuvenation; and it was one of her greatest albums in a history that spanned over six decades.