A few years ago, Sigur Rós started making pop songs. The shift was, like everything the band has done, patient and considered. Consider: it took the band almost ten years to transition slowly away from Ágætis byrjun‘s grandiosity and the goodwill it engendered to the English-singing, traditionally structured, and easily consumable joy of Með suð í eyrum við spilum endalaust. During that time, de facto band leader Jónsi’s solo work went even further in the crowd-pleasing direction, as Riceboy Sleeps and — in particular — Go came off as pop music made for Fox Searchlight movie trailers. But even despite claims that came as early as 2009, whispers that the new Sigur Rós record would be more ambient, it wasn’t hard to think that the original recording sessions for what would become Valtari would continue down the path they had to that point been carving over the course of their career. But whatever the band was trying, it didn’t work, and the band scrapped the recordings and went back to the drawing board.

It took them another few years, but with Valtari, the band has returned in some ways to the sounds it made its name with. The deliberate pace of their latest record is reminiscent of the intentional ambiance of ( ), the iceberg opulence of Ágætis byrjun, and even the formative chrysalis of Von. Take “Varðeldur”‘s six minutes of beautifully ornamented piano that could have sat quietly next to ( )‘s third track. Or “Varúð,” which contains one of the record’s few thunderous moments and marches in time with both “Ný batterí” and “The Death Song.” And “Dauðalogn” is the funereal cousin of “Starálfur,” slowing the latter’s lush string sections to a crawl and its vocals to a whisper.

The band now does this sort of thing — hushed, haunting, monolithic, translucent — better than they did earlier in their career, which is weird since that’s how they made a name for themselves. It’s something to do with Alex Somers’ production, which he honed working on his partner Jónsi’s solo albums. There’s space and separation for all of the elements to breathe, and that room makes the silences heavier and headier than they ever were on ( ). The subtle shift halfway through “Ég anda,” where atmospherics are replaced by more tangible instrumentation and layered Jónsis create some sort of angelic fey chours, is a perfect example how this attention to space pays dividends on the record.

And their experience with writing pop songs means that when they do go for a melody, it’s a striking one. “Fjögur píanó,” which translates to “Four Pianos,” is both a perfectly accurate description of what you hear in Valteri‘s closing track, and a reminder of what Sigur Rós can do with just a handful of tumbling, measured notes arranged in major key. It’s almost completely haphazard, but with enough form and shape to conjur up sunsets or any number of hazy Instagram filters. Throughout the record, the band’s melodies don’t traffic in easy payoffs or obvious bombast, instead they work through Somers’ huge silences, and through vast expanses of time.

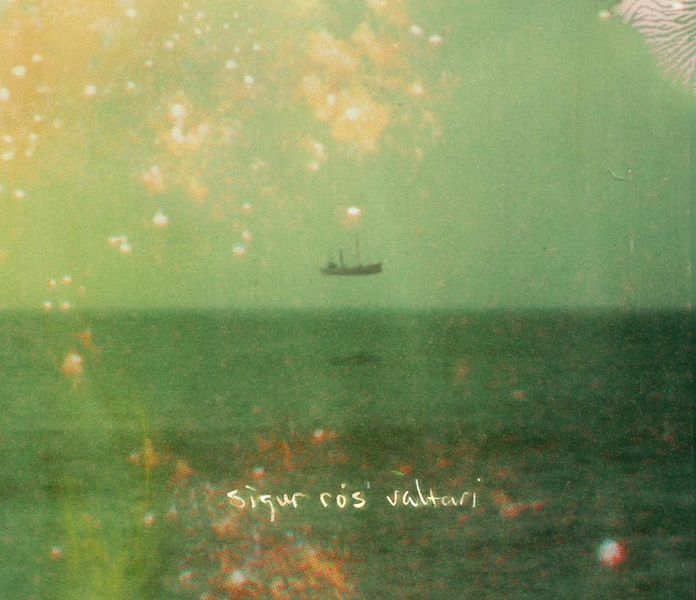

The album name, Valtari, translates from Icelandic into English as “Roller” or “Streamroller.” While that may seem apropos exactly nothing regarding Sigur Rós, the band is less trying to imitate heavy construction equipment and more paying homage to the steady, insistent nature of a valtari’s movement. Just like it’s easy to imagine the band using Valtari‘s original recording sessions to try to out-cotton candy their most recent efforts, it’s equally easy to imagine that, when those sessions turned up nothing worth releasing, Sigur Rós scrapped everything, took their time, avoided cheap thrills and outlandish statements, and submitted a powerfully gentle album; the first sheet of ice covering the lake.