There’s a combination bar slash performance space under Baltimore’s rib cage, well-removed from the ridiculous shine of the Inner Harbor, Camden Yards’s regal shadow, and all the must-sees, but not so far away that you confuse where you are for somewhere else. If you find yourself there on a certain night, you’ll wander in on a crowd composed of smaller circles whooping their approval for the masked breakdancers in their nuclei, raising beers and voices as the acrobats land the last spins of their routines–probably one of many they’ll bust out that night.

Around them you’ll see students from the local arts school, or from the reasonably well-known local medical school, professionals, burnouts, freegans, parents…all participating toward the sum of the experience, hanging out in the language of Baltimore, a city that doesn’t get brought up much except by your friend who just watched The Wire. It’s this kind of inclusive, separate-but-together psyche, an individual’s translation of the collective’s tongue, with the darker corners, too, accounted for, that Dan Deacon honed into 2009’s Bromst, a high-caliber onomonopiac slug with enough sizzle to fry your noggin, and uses as the zoomed-in launching point for the widescreen sweep of America, his most ambitious project yet.

And in terms of composition and form, America is not a wild departure. The album’s detractors will likely cite this as their chief complaint–too similar, too “easy,” whatever. While this is probably Deacon’s most forgiving entrance point, there’s plenty to tickle the ear holes of devoted fans as well. Remaining are the impossible piano runs, octopus drums, chipmunk vocals, and those typically-Deacon standout chimes, bells, things that go “ding,” integrated as if by lasers into tracks that propel forward, double back on themselves, and come out the other side changed for having been through it. To his credit, it only sounds mechanical when it’s supposed to, like in the beginning of “Crash Jam,” which clomps, whirrs, and, yep, rock ‘n’ rolls its way through a wormhole, with Deacon as the guru-voice floating almost lazily through scattershot fireworks of percussion. But everything here is bigger, and feels more important and wise, even than the spectrum of ego on Bromst. Though it can at times feel like there’s an intimacy missing, the difference is like stepping outside.

He can’t help himself. The album reaches for aesthetic nirvana, and sometimes even reaches it, like on the stunning instrumental “Prettyboy,” a serious contender for “loveliest” song of the year, largely because, while it piles the wrenching signifiers on with a generous hand, it does so without shame. Here, Deacon closes the track with subtraction, pulling back the layers of processed material until all that remains is the song’s elemental bloodline–long bowings of strings, glowing, blinking woodwinds–a sort of thesis-moment, not necessarily that there is, below all artifice, truth–but that things possess an inherent, sometimes buried, but undestroyable quality. It’s by no means the world’s most original sentiment of patriotism, but a good one. And it’s rare, maybe, but there are things in this world, and as Deacon would have us believe, in America, that feel like they’re made of light.

America is an album in two halves, once again separate but together, a side of individual tracks and a four-song suite that inform each other even as they generate tension by nature of their disparity. Opening the whole thing is the pummeling sound-check-cum-rambler, “Guildford Avenue Bridge,” which willfully interrupts itself from drifting too far–early evidence of the album’s precise, focused songcraft, even whilst handling the ineffably huge–and sets the zero from which its thematic register is based. It possesses the skeleton of what follows, sure, but is delightfully uncomplicated alongside many of its sister tracks. “True Thrush,” the record’s first single, ambles prettily, helmed by a bouncing bassline before squelching sideways as its sections mutate. The gesture is bold and smart–each shift feeling like a lateral movement that trickily advances the song into what it becomes.

Among the developments Deacon’s made that sit closest to foreground has to be attention to the songs’ lyrics, which place the record in its desperate, hope-clinging, and sometimes awestruck ethos, and frame the narrative of its utterance, the artist’s (re)discovery of a nation and his place in it. On the punky call-to-arms “Lots,” he howls his condition to the scarred landscape, insisting as if in defiance–even in the wake of crushing loss and waning faith–the days continue, the world spins madly on.

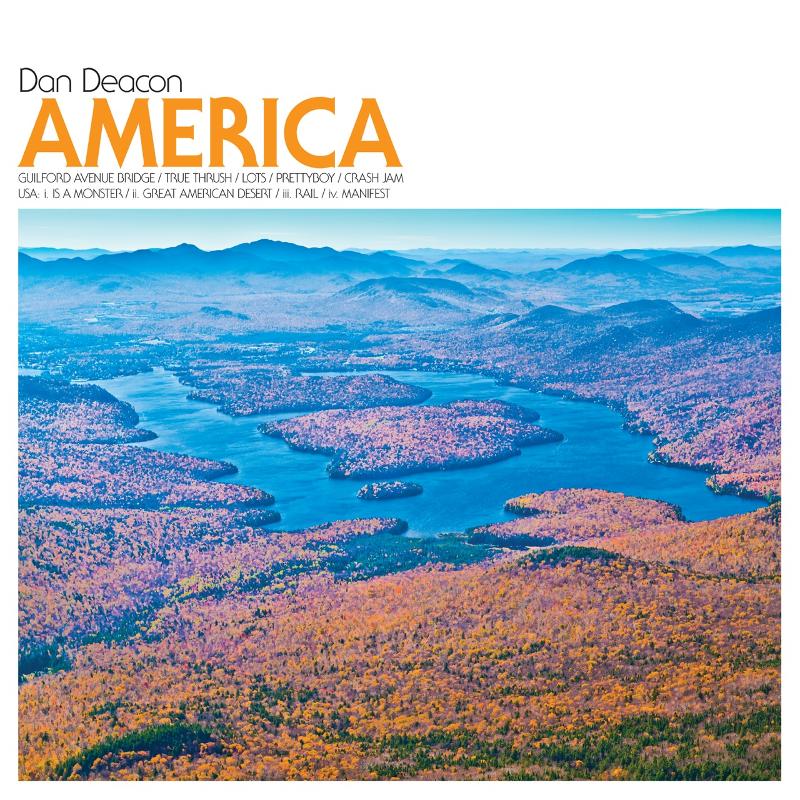

Which brings us to “USA,” the four-part medley that comprises America’s latter half: a tribute, interpretation, adaptation, work of process, and salute to the wild, romantic expanses of America–its faces, landscapes, symbols, social politics, good and bad–as seen by the third eye of a dude from Baltimore, who makes art in a dialect of Baltimore, a dialect of the good ol’ US of A. That it comes off sounding like an adventure is perhaps its most supreme accomplishment.