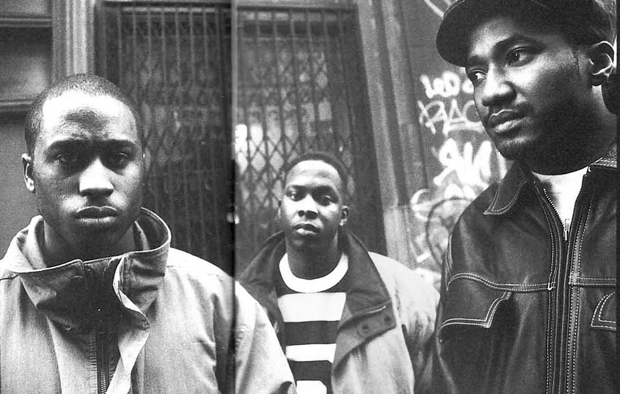

The most telling moment of Beats, Rhymes & Life, director Michael Rapaport’s terrific new documentary on alternative-rap pioneers A Tribe Called Quest, was this from Phife Dawg: “I love hip-hop, but at the rate it’s going, I could do with or without it.” It’s not uncommon in 2011 to hear rap’s elder statesmen bemoan the commercial direction the genre has taken in recent years, but it’s particularly fascinating in the case of this group, which hasn’t put out any new music since 1998, but can be counted on most years as a fixture on the summer festival circuit. Hip-hop may just now be entering the stage in its development where it’s viable for legends to exist as nostalgia acts, and if there’s one thing this film makes clear, it’s that Tribe are leading the way here just as they did 20 years ago in the booming jazz-rap movement.

Intentionally or not, Rapaport’s film builds a case for A Tribe Called Quest as hip-hop’s answer to the Rolling Stones in more ways than one. In fact, if you squeezed the Stones’ career arc from 50 years down to 20, you’d end up with something a little like Tribe. The importance of their first three albums to the last two decades of hip-hop cannot be overstated any more than that of the opening riff of “Satisfaction” on every rock guitarist of the last 45 years. Virtually every rapper that could be described as “conscious” or “underground,” or, really, anyone who doesn’t identify with the idiom of gangsta rap, is indebted to Tribe in some way. Q-Tip and Phife Dawg were one of hip-hop’s first truly great emceeing tag teams, blending and intertwining their distinctive deliveries as deftly as Keith Richards and Mick Taylor wove their guitars during the Stones’ late-‘60s/early-‘70s glory years. When it comes to influence, innovation, and creating a body of work that stands up several decades after the fact, you’ll never hear anyone call either of these two groups “overrated.” It wouldn’t even be an argument worth entertaining, and anybody who tried to make it would be laughed out of the room.

But where Tribe’s first three albums – 1990’s People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, 1991’s The Low End Theory, and 1993’s Midnight Marauders — were the stuff of legends, they entered their Steel Wheelchairs phase almost immediately thereafter. Their next two albums, 1996’a Beats, Rhymes & Life and 1998’s The Love Movement, were a shell of the group’s former greatness. The sound was there, and the songs (like “Phony Rappers” and “1nce Again”) were occasionally memorable (remember, the Stones were still capable of the occasional “One Hit [To the Body]” during their ‘80s and ‘90s run of forgettable albums), but something was off. A Tribe Called Quest were going through the motions, and when they called it a day following the Love Movement tour, it seemed more of a formality than a tragedy.

This, of course, is where Rapaport’s film gets interesting. Tensions between Tip and Phife had been mounting for a few years by this point, with Phife’s health problems occasionally derailing the group’s performances and Tip’s musical ambitions alienating the other members. Hearing Phife explain his supposed marginalization at the hands of Tip, all I could think of was Keith Richards’ recounting of his falling-out with Mick Jagger in his recent memoir Life. According to Keith, the majority of his disdain for Mick stemmed from the frontman’s leveraging of the Stones’ record contract into a solo deal for himself in the mid-‘80s. Talking to Rapaport, Phife seems to draw similar conclusions about Tip’s intentions.

When Tribe did reunite in the mid-2000s, the motivations were purely financial. Phife’s health had worsened following the breakup, and when he needed a kidney transplant, the group was finally resigned to biting on one of the many reunion offers that had been pouring in since they disbanded. The most sadly poignant moment in Beats, Rhymes & Life comes near the end, when Dave Jolicoeur of fellow rap legends De La Soul, then on tour with the reunited Tribe at Rock the Bells, remarked that he wished his old friends would break up again, knowing the condition of the relationship between Tip and Phife offstage (Tribe’s other two members, Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Jarobi White, mostly come off as innocent bystanders to this infighting in the film and don’t get nearly as much screen time as Tip and Phife). All four members stress repeatedly that the group has no plans to continue to make music together, and there’s no sense that Tip and Phife would have any relationship at all today if they weren’t raking in the festival dough every summer.

This is where A Tribe Called Quest’s similarities to the Rolling Stones come full circle. By Keith Richards’ own admission in his book, he and Mick don’t consider each other friends today. The Stones continue to tour only because it’s what they’ve been doing for most of their lives (and, you know, because of the hundreds of millions they pull in every time they hit the road). This is the stage Tribe is at in their career, and it’s a relatively unique one in the world of hip-hop.

The genre is still young enough that there aren’t too many out-and-out oldies acts yet. The Wu-Tang Clan doesn’t put out too much music as a group anymore, but there’s so much cross-pollination among members’ solo projects that touring as a unit only seems logical. Jay-Z’s and Nas’ creative peaks are almost certainly behind them, but they both still release new music regularly and it’s (usually) reasonably popular and well-received. Ditto Snoop Dogg. But Tribe? They tour constantly now, most recently performing Midnight Marauders in its entirety at last summer’s edition of Rock the Bells, and they don’t even release new music to have something to sell at merch tables. Nobody’s begrudging them this — God knows they’ve done enough for the development of the genre to earn them the right to cash in on those peerless first three albums until the day they die. I’ve seen them twice since the reunion, and like the Stones plowing through “Brown Sugar” for the millionth time, hearing Phife spit his seminal opening verse in “Buggin’ Out” is enough to remind us why we still care, something Rapaport’s film only reinforces.