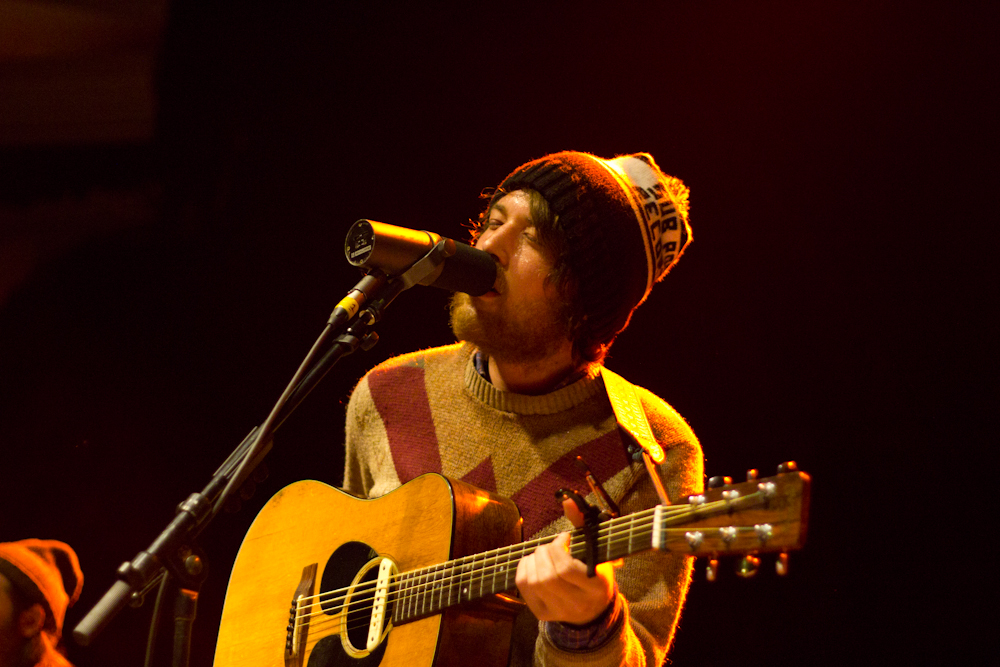

“Losing Myself,” is set firm in the quiet reflective tone of minor key guitar. The “I” is repeated and seems to enclose the song like rising water. “I’m a fast breather/I’m a hairless dog,” which rises as a curious preceeding step to, “I am just like the gathering fog.” The description seems self-defeating and occludes rather than explains. Indeed, by the time, Ed Droste joins him on, “I’m a slow-mover/I’m the best-laid plans,” it seems more like a lie and an excuse than a fair assessment. The duplicity of the description layered on as the two sing in the first person. There are competing images that mirror the harmonic technique.

Though, the voices are never in competition. Droste sings the high to Pecknold’s cavernous croon. The two voices pour into into another with the picked guitar providing a skeleton over which the elegant body of the song moves. The hushed guitar gives easily to the voices, but also to the spaces between those notes and Droste/Pecknold’s alternate sighing of the lyrics. Silence becomes a fourth instrument in the song.

By and by, the whole thing does make one grossly aware of how much delight an audience will take in tragedy. It is a good song, an enjoyable one that does wear out too quickly. Is it the empathy I’m missing or something to cry to? Or is it simply wonderful independent of how relentlessly personal it becomes? It’s the subject of another discussion, but it’s an asset to the song that the story’s individual and personal narrative finds a space for a listener in those silences.

“Derwentwater Stones,” is slightly less aloof and has Pecknold marking time with a playful guitar line that beckons forth nearly like the “come along” of his muse that beckons him forth into the night. The sound is pastoral and weathered like a tale told too many times, but the sound is one of which one can never tire.

Pecknold’s voice gently echoes and dissappates into his own fictional landscape he dictates, creates-by-saying and follows down to the stream where the stones lie. Someone is gone, absent, “told me to be good/now I’m on my own,” but the song still inspires a taste for exploration. A hungry eye takes the night scene in like poetry like the hungry ear takes in the song substituting excitement and a need to tap a foot for mere noise and sonic wavelength. Things become more than what they are.

Then, things becomes again concretely what they are, rooted in real time and place in “Where Is My Wild Rose.” In this tune, Pecknold revists a song by New Zealand musician Chris Thompson. The American and New Zealander meet in the middle in Ireland for a tale punctuated by Dublin and Killarney. The updated version remains faithful to the original, if not a bit more positive in the major key. “Where is my wild rose?” anchors the song’s seeking aesthetic. The lyrics take us on a path trailing a love through Ireland. Hints come our way, “rich sweet brogue/red remembered,” but the listener is teased into self-reflection as they come to the words, “They said you passed as a ghost/Walks through the hazel wood/Or Aengus searching for his love/Walks through the hazel wood.” A swap occurs of ghost/Aengus/narrator/listener where each becomes unsecured from stable roles, get immaterial just like the ghost. The final verse as a repetition of the first, like the repetition of being in the ghost: the person is repeated. Pecknold wears the lyric well, bounding in the same way Thompson played it in 1974. Though, maybe because it is a cover, it is at times played with a little less emotional investment than the other three. No doubt: any emotion in a rehearsed-rehearsed-then-performed piece is illigitimate, but the performance defies a simplistic understanding of genuine and false. In this case, the performance just isn’t there at some parts.