Works

You already know Tchaikovsky’s music, you perhaps just don’t realise it. Just take this chirpy little number by Public Image Limited – buried deep somewhere in that caustic guitar line is the main theme from Swan Lake:

Public Image Ltd. – “Death Disco”

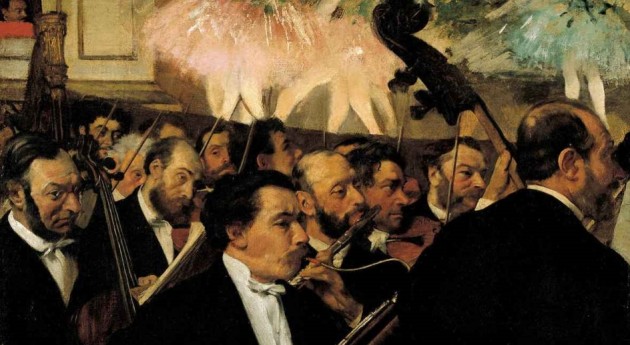

Tchaikovsky’s most significant music is predominantly orchestral, but is split into a number of different areas, some traditional, others experimental, reviving old forms, imparting new seriousness to previously trivial genres, or experimenting with entirely new structures. He explored both “absolute” and “programme” music, historical and progressive tendencies, and could never be pinned down in his restless creativity. I want to begin by talking about the two famous concertos I already mentioned, because they provide the best possible introduction, showing Tchaikovsky at his best – musically rigorous and structurally compelling, but also virtuosic, full of enormous tunes, and highly entertaining.

Here’s Piano Concerto No.1 – The first movement, with its unmistakable “power chords” opening, made all the more impressive for the fact that Tchaikovsky was not a particularly great pianist:

Piano Concerto No.1 – 1st movement – Allegro Non Troppo

The delicate slow movement, full of beautiful solo parts, especially for the woodwinds:

Piano Concerto No.1 – 2nd movement – Andantino Semplice

And the feverish final movement:

Piano Concerto No.1 – 3rd movement – Allegro con fuoco

The balance of the dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra in this work was something that Tchaikovsky never achieved quite as successfully in the works which followed it, mainly as the result of his curious aversion to the sound of strings combined with a piano, of which more later. The second piano concerto is a little bloated, and shows signs of the emotional damage done by the collapse of Tchaikovsky’s marriage. The final movement, however, is well worth listening to, thanks to its brilliant Mozartean energy:

Piano Concerto No.2 – 3rd Movement – Allegro con fuoco.

Leaving aside the confusing mess surrounding the fragmentary third piano concerto, and the unclassifiable whimsy of the Concert Fantasia, we move on to the rather more successful and popular Violin Concerto, which ranks as one of the finest, and most technically challenging works written for that instrument. Here’s the first movement – just wait for the stunning melody which kicks in after 1:15, which has the feeling of a timeless folksong –

Violin Concerto – 1st Movement – Allegro Moderato, Part 1

Violin Concerto – 1st Movement – Allegro Moderato, Part 2

The second movement also brings a singing quality to the instrument, turning slightly sinister at the end:

Violin Concerto – 2nd Movement – Canzonetta

Then, just when you thought you were safe, the third movement explodes and lets out a flood of furious violin passages:

Violin Concerto – 3rd Movement – Allegro Vivacissimo

Tchaikovsky never wrote a fully-fledged cello concerto as some of his compatriots and contemporaries would later do, but he did write a set of “Variations on a Rococo Theme” (nothing to do with Arcade Fire or Bill Callahan) for Cello, which comes close to the concerto form. You can listen to the whole set here or just skip to the final, impossibly difficult final variation:

Variations on a Rococo Theme – Variation VII and coda:

Before moving on to the symphonies themselves, we need to deal with Tchaikovsky’s freestanding orchestral works, some of which are amongst the most popular of all his pieces. In Germany, many of these pieces would have been referred to as “symphonic poems,” a rather grandiose term invented by Liszt, which simply means an extended orchestral work in one continuous movement, which generally follows some kind of extra-musical narrative – another manifestation of “programme music.” Tchaikovsky seems to have been reluctant to use these terms, titling the works variously as overtures, fantasy overtures, festival overtures, and so on. Whatever you call them, these pieces are amongst the most dramatic and evocative of his works. Tchaikovsky frequently drew on literary sources for inspiration in these pieces, especially those with tragic heroines. In his earliest significant work of this kind he turned to Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. You don’t realise it, but you already know the famous “love theme” from this piece, which has been used in countless films and adverts. But to extract one moment from this expansive piece does a huge disservice to Tchaikovsky. At the start of the piece, try to imagine a sunrise over the city of Verona, until about 5:51, when the Montagues and Capulets come out to fight, and different parts of the orchestra battle for the upper hand. Then, at 7:55, listen out for the seamless transition into the love theme. You can work out the rest for yourself.

Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture – Part 1

Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture – Part 2

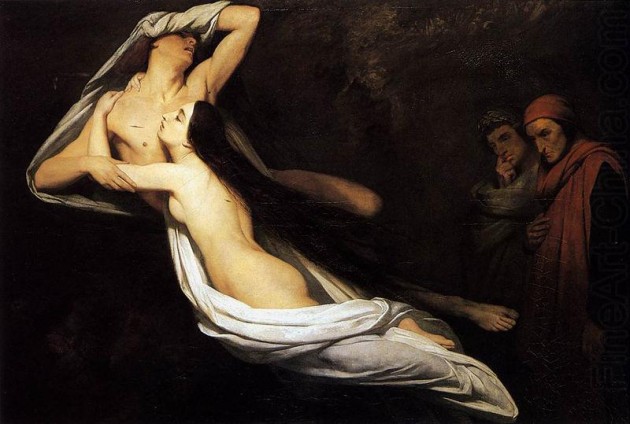

Later, Tchaikovsky turned to the story of Francesca da Rimini, from Dante’s Divine Comedy, which tells of a woman who falls in love with her ugly husband’s brother, only to be cast down the second circle of Hell as a punishment, caught in a perpetual embrace with her lover. The start of this explosive piece, perhaps Tchaikovsky’s most startling and vivid, depicts the descent into Hell, then from about 3:40 we hear the violent winds buffeting the souls of the damned, intensifying around 4:50 before the real orchestral pyrotechnics begin. In the second part Tchaikovsky attempts to recount Francesca’s tragic story in musical terms, before the return of the swirling winds and main theme in the last part. Tchaikovsky remarked that the piece was composed “with love, and that love, it seems, has come out quite well” – and I’m inclined to agree with him. For added fun, why not try conducting along at home?

Francesca da Rimini – Part 1

Francesca da Rimini – Part 2

Francesca da Rimini – Part 3

While there are several other symphonic poems that are worth perusing if you enjoy Tchaikovsky’s style, such as The Tempest, Hamlet, Fate, The Storm, and Voyevoda, there are three much more popular, and far less serious pieces to talk about. Firstly, the 1812 Overture, possibly one the most well known and truly ridiculous pieces of music in existence, which was written to commemorate Russia’s victory over Napoleon, but has also come to represent America’s “second war of independence” in the same year against Britain. Although we (Britain) did manage to burn down The White House. But anyway. Tchaikovsky himself didn’t think much of the piece, which stipulates the use of real cannons and church bells in its finale, but it is quite fun nonetheless. It incorporates Russian church music, as well as the French and Russian national anthems in a bombastic evocation of war which often prevents people appreciating Tchaikovsky’s more subtle pieces. The lazier listeners amongst you should skip straight to 13:55.

1812 Overture:

Need more musical triumphalism? Fortunately Tchaikovsky considered that eventuality, and composed the menacing Marche Slave, so called because it was written as a gesture of support for what Russia saw as an attack on fellow Slavs in Serbia. Things start to get truly evil around the 2:15 mark.

Marche Slave:

Finally we have the product of Tchaikovsky’s many visits to Italy, the bizarrely spelt Capriccio Italien, which is how I imagine a symphony by Verdi might have sounded if he had ever felt the need to write one. Tchaikovsky was inspired in this piece not only by opera and the street songs he frequently heard in Rome and Florence, but also by his predecessor Glinka’s own musical exoticism. The piece begins with a brass fanfare inspired by Tchaikovsky’s time spent in a Roman hotel next to a barracks. This is followed by a sultry dance theme, then at around 4:40, the magic starts, and the Italian carnival is unleashed.

Capriccio Italien:

Tchimes of Freedom

Finally we reach the symphonies, which are not always the most popular of Tchaikovsky’s works, but deserve to be taken more seriously as a central plank of his output. Tchaikovsky didn’t live long enough to become a victim of the famous curse of the ninth, but did manage to produce six numbered symphonies, and another piece known as the Manfred Symphony, in between numbers four and five. If that seems confusing, you have no idea. Here are some highlights from the first three symphonies, which don’t have quite the same maturity and unity of conception as the other four, but are still excellent:

Symphony No.1 “Winter Daydreams” – 3rd movement – Scherzo: Allegro giocoso

This finale is slow at first but really hits its stride around the four minute mark:

Symphony No.1 “Winter Daydreams” – 4th movement – Andante lugubre, Allegro maestoso

A rushing, excitable scherzo:

Symphony No.2 “Little Russian” – 3rd Movement – Scherzo, Allegro molto vivace

Followed by a grand finale which quickly turns into a hugely enjoyable romp using Ukrainian folk tunes which give this symphony its name:

Symphony No.2 “Little Russian” – 4th Movement – Finale, moderato assai, allegro vivo

The third symphony has an unusual five-movement structure rather than the usual four, mimicking Schumann’s Rhenish symphony from 25 years before. The “polacca” dance rhythm of the final movement gives the symphony its nickname “Polish,” but since the second movement is marked “alla tedesca,” it could just as easily have been called “German.” Here’s the fluttering fourth movement and the thunderous finale:

Symphony No. 3 “Polish” – 4th Movement – Scherzo: Allegro Vivo

Symphony No. 3 “Polish” – 5th Movement – Finale: Allegro con fuoco – Tempo di polacca

Finally we reach the truly mature symphonies. A lot of people like to go on and on about how great the fifth and sixth symphonies are, but to me, you just can’t beat the fourth. It might not be the most profound or sophisticated symphony, but it is certainly the most punchy, succinct and well, just loud. Each movement is distinct, but judicious use of a repeated motif stated at the very start ties the work together. Tchaikovsky dedicated the piece to his long-time supporter and patron Nadezhda von Meck, who provided the composer with a regular salary, on the curious condition that they should never meet in person. Instead, over their relationship, they exchanged more than a thousand letters, including one in which he gave a detailed description of the meaning of the fourth symphony, which you can read here, but if you can’t be bothered with that, just keep in mind that, like Beethoven’s fifth, it deals with the idea of fate, which manifests itself in the ominous opening horn parts:

Symphony No.4 – 1st Movement, Andante sostenuto – Moderato con anima – Part 1

Symphony No.4 – 1st Movement, Andante sostenuto – Moderato con anima – Part 2

The third movement is a lot of fun, mainly because it has one of the longest bits of continuous pizzicato (plucked strings) in any piece I can think of:

Symphony No. 4 – 3rd Movement, Scherzo: Pizzicato Ostinato

And once again, after a delicate interlude, Tchaikovsky hits you over the head with a frying pan:

Symphony No. 4 – 4th Movement, Finale: Allegro con fuoco

The fifth symphony is the greatest piece that Wagner never wrote, sprinkled as it is with endless permutations of the same motif, which appear most prominently at the start of the first and fourth movements, initially slowly and mournfully, with clarinets and low strings, but finally as another grand march. Wagner used this idea of a repeated theme in his operas to mark the appearance of particular characters, a concept which is now taken for granted in films, but Tchaikovsky was amongst the first to use it to unify an entire symphony. Also, because of its popularity in the Second World War as an emblem of triumph over adversity, it has, like Shostakovich’s seventh, come to be associated with the Siege of Leningrad. Unlike the fourth, but in common with the sixth, this is a complex and melancholy work which takes time to unfold and present its most interesting material, and merits repeated, careful listening. After a slow introduction, the first movement gathers pace around 2:45 and builds from there into a series of climactic moments. The second movement is sweeping and sumptuous, but a sinister note is struck around ten minutes in when the main theme returns. This is followed in the third movement by an elegant waltz, before the finale, which is the final reiteration of the central theme, which appears now with renewed purpose.

Symphony No. 5 – 1st Movement – Andante, Allegro con anima

Symphony No. 5 – 2nd Movement – Andante cantabile

Symphony No. 5 – 2nd Movement – Valse, allegro moderato

Symphony No. 5 – 2nd Movement – Andante maestoso, allegro vivace

The sixth, or “Pathétique” symphony is the most tragic and beautiful of all Tchaikovsky’s works. He conducted it just once before his death, and it has come to be regarded as a kind of tacit requiem. The work contains massive contrasts, beginning with an uncompromisingly bleak and eerie movement where a bassoon seems to emerge out of a fog of strings, before taking a number of unexpected and dramatic turns. In the first part of the first movement, watch out for the change at 2:10, and again around the ten minute mark, as well as around 2:55 in the second part of the first movement, when a massive blast of brass arrives. The second and third movements provide some light relief, before the deathblow of the last movement. Instead of ending on his customary triumphant note, the Pathétique ends with a consistently elegiac mood, overflowing with tormented melodies before eventually fading away, back into the gloom. Tchaikovsky never revealed the true meaning of this piece, and it has been interpreted as a suicide note and as an expression of his morbid obsession with his nephew Bob Davydov, to whom the work is dedicated. But once again, this is music which requires no verbal explanation in order to be understood.

Symphony No. 6 – 1st Movement – Adagio, allegro non troppo, part 1

Symphony No. 6 – 1st Movement – Adagio, allegro non troppo, part 2

Symphony No. 6 – 2nd Movement – Allegro con grazia

Symphony No. 6 – 3rd movement – Allegro molto vivace

Symphony No. 6 – 3rd movement – Finale: adagio lamentoso

The “Manfred” Symphony saw Tchaikovsky return to literary sources, specifically this exceedingly long poem by Byron, who had also served as inspiration for Berlioz and Schumann. This piece has long divided opinion, but I think it’s great, not least because it is one of the few successful programmatic symphonies after Beethoven’s sixth. Tchaikovsky wrote some detailed notes on exactly which aspects of the poem he was trying to evoke, but since this is such a complex work I’ll just provide this helpfully annotated version of my favourite movement.