Benedictus

Leopold Mozart was a devout Catholic, and referred to his son’s abilities as follows: “this miracle is too evident and consequently not to be denied, they want to suppress it. They refuse to let God have the honor” – clearly a rebuke to the enlightened values that were gaining ground in his lifetime. The extent of Wolfgang’s religious devotion is the subject of some debate, but his services to the Catholic Church were nonetheless considerable, even though he did defy the Pope by transcribing from memory a famous work which was only allowed to be performed in the Sistine Chapel. Mozart’s sacred works often posses a more solemn, serious quality which befits their use. Here are some of the best.

The Great Mass in C Minor, with its ominous opening Kyrie and haunting Qui Tollis:

Great Mass in C Minor, Kryie

Great Mass in C Minor, Qui Tollis

The Agnus Dei from the Coronation Mass is also deservedly famous:

Coronation Mass, Agnus Dei

Among the most calming of Mozart’s religious pieces is the Laudate Dominum from the Solemn Vespers, sung in this case by Cecilia Bartoli, who is normally completely and terrifyingly insane, but keeps things simple here:

Solemn Vespers, Laudate Dominum

On a similar note, here’s the soothing and hugely popular Ave Verum Corpus:

Hello Opera(tor)

“For most listeners, opera has vague, mostly derogatory connotations: old, imposing, foreign, dead, faintly ridiculous.” – an insightful comment from an agricultural implement discussion site.

I’ve been saving what are arguably some of Mozart’s greatest achievements until the very end. Why? Because I’m talking about his operas. Yes, opera, that word which can strike fear into the hearts of even the most ardent devotees of difficult music. But opera is really nothing to be afraid of – once you get past the stereotype of the fat lady singing. The word itself just means “work” in Italian, and over four centuries that definition has encompassed a huge range of material, but at heart, what opera is really about is quite simple – great songs, within the framework of a larger drama. The plots tend to be completely ridiculous, so really it’s best to concentrate on the music. Coming to terms with opera can be difficult, but once you overcome the stylistic hurdle it presents, the rewards to be reaped are enormous. And don’t just take my word for it, everyone from Kurt Weill to The Knife has engaged with opera, with varying degrees of success. While opera is easy to mock for being melodramatic, sentimental and over-the-top, I would contend that these are actually its greatest virtues, especially in the face of the kind musical fussiness and overwhelming earnestness which afflicts certain musicians today. Mentioning no names.

Operas can be huge, unwieldy and difficult to get to know, but Mozart’s provide the best justification and most accessible entry to this intimidating genre. Before talking about them, it’s best to clear up a few technical terms. Firstly, the Aria. An aria (Literally “air” in Italian) is simply a discrete song for one singer within an opera. In fact, you probably already know some famous examples – like the one by Delibes about British Airways, the one by Bellini about perfume that attracts sailors, the one by Verdi about the elephants, the one by Puccini about football, the one by Gershwin that you thought was just a jazz standard, and of course, the one Mozart wrote for Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman to listen to in prison. You might even know this obscure number by Wagner, which is slightly better known in its English version.

Secondly, recitatives – these are the things that really put people off opera, and to be honest, unless you’re watching it live, have a translation to hand, or really care about the plot, there’s not a lot of point in listening to them. Recitatives are the parts in between the arias and choruses where characters speak to each other to drive the story along. The difference between recitatives and dialogue in say, a musical, is that all of it is sung, but in a less melodic style than an aria, with minimal orchestral accompaniment and rhythms that imitate ordinary speech. During the nineteenth century, composers like Wagner started integrating arias and recitatives together into a continuous flow of music. Such works are described as being through-composed, and are a lot more challenging to listen to than clearly compartmentalised operas of the kind that Mozart wrote.

Thirdly, overtures, which are instrumental preludes which introduce the piece, often (although not always) quoting melodies from arias which appear later. Next – the Libretto, this is the text which includes all of the opera’s dialogue and lyrics. Lastly we have the Singspiel, which is simply a German variety of opera, where dialogue is spoken rather than sung – hence the name, which simply means “song-play”. And that’s really all you need to know – things like duets, trios, choruses and so on are self-explanatory, and while other terms can be interesting, they aren’t essential to enjoy the artform.

Mozart wrote operas from childhood, but it is the series of three Italian works written towards the end of his life in conjunction with librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte for which he is best known. This collaboration ranks as one of the greatest in musical history. As a writing team, Mozart and Da Ponte worked extremely closely to match the text to the music with a thoroughness and attention to detail that had rarely been achieved before. Mozart frequently used word-painting to achieve this effect, but don’t worry about knowing exactly what’s going on – the music usually speaks for itself. Besides, translations have never been easier to find. The first of the Mozart & Da Ponte operas, “The Marriage of Figaro”, was written in 1786. It was based on a play of the same name, a then-controversial satire on the decadent French aristocracy written by the French polymath Pierre Beaumarchais. This opera is one of the most popular and well-known ever written, and remains one of the most frequently performed. Here are just a few of the best known numbers:

Overture:

Se vuol ballare, in which Figaro subversively mocks his master and the aristocracy in general:

Porgi amor qualche ristoro:

Non più andrai:

Voi che sapete:

Dove sono i bei momenti:

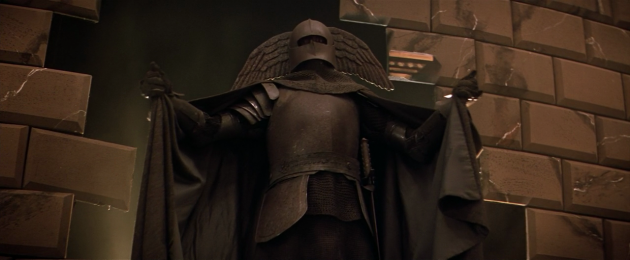

Next comes “Don Giovanni,” a reworking of the classic Spanish legend, Don Juan, in which a notorious womaniser, whose life consists mainly of drinking and violence, is ultimately terrorised and dragged off to hell by a man he has killed. This opera is a strange mix of comedy, horror and song, and has a final climactic scene which has to be seen (and heard) to be believed:

Overture:

Là ci darem la mano – in which Don Giovanni seduces Zerlina, who has only just got married to someone else):

Fin ch’han dal vino – also known as the Champagne aria:

Madamina il catalogo è questo – also known at the catalogue aria, in which Don Giovanni’s servant Leporello recounts the hundreds of women Don Giovanni has conquered across the world:

Deh, vieni alla finestra, a serenade with a mandolin:

Don Giovanni, a cenar teco m’invitasti – also known as the Commendatore scene, in which the man Don Giovanni killed comes back from the grave. Probably the most powerful scene in any opera, and more effective than most zombie films:

Finally comes Così Fan Tutte, known in English by the rather politically incorrect title “Women are like that.” It is a story of a love square rather than a love triangle, soldiers, disguises and confusion. The slightly salacious character of the story meant that this opera was unfairly neglected, but with four main characters, it is full of great excuses for duets, trios and quartets:

Soave sia il vento, perhaps Mozart’s most beautiful aria:

La mia dorabella:

Un’aura amorosa:

Una donna a quindici anni: