Symphomaniac

Brahms didn’t publish a symphony until his mid-forties, having spent a decade tinkering with different ideas, but once he got over that hurdle, he really hit his stride. His symphonies show off his full expressive range, and his total mastery of orchestration. To me, Brahms’ symphonies are worthy successors to Beethoven, but they are so much more than just that. Instrumental music of this calibre, while apparently dry and “absolute” is in fact richly evocative, summoning up a whole world of emotions and images in the mind of the listener. Music like this doesn’t tell you exactly how to think or feel, but allows you to drift through a landscape of ambiguous sounds and symbols, providing a deeply subjective experience. Lyrics, be they in opera or in indie rock, can never give quite the same effect, because they demand much more specific kinds of interpretation. If you’ve ever heard and enjoyed something like Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, then you’ve probably encountered this slightly abstract way of listening before.

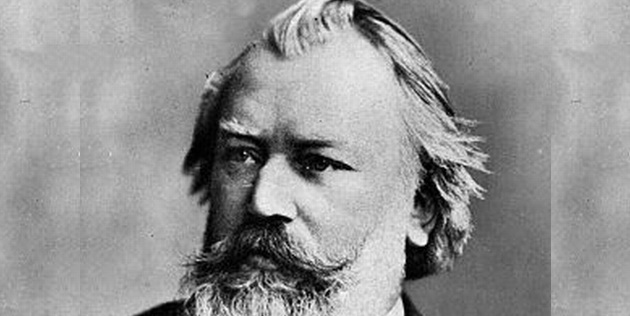

Rather than force you to sit through all two and a half hours of orchestral music, I’ve just picked out a few of my favourite movements from Brahms’ last two symphonies, conducted by Herbert von Karajan (pictured above), one of the composer’s most gifted interpreters. If you are interested in hearing the full works, however, you can find them on the Spotify playlist at the start of the article. Let’s start with a section from the 4th symphony, which hits you like a musical juggernaut:

Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, 3rd Movement – Allegro giocoso:

Followed by the tormented last movement, writhing and screaming in agony:

As a tedious musicological footnote, let me add that Brahms’ 4th does the opposite of what Beethoven’s fifth does, by moving from major to minor, suggesting defeat rather than triumph. Next up is the opening of the 3rd symphony, where the orchestra moves deftly from exploding supernovae to the sweetness of a lullaby:

Symphony No. 3 in F Major, 1st Movement – Allegro con brio:

And then the soft musical pillow the 3rd movement:

Symphony No. 3 in F major, 3rd Movement – Poco Allegretto:

Brahms took his symphonies extremely seriously, but occasionally wrote “orchestral serenades,” which are basically lighter versions of symphonies. Brahms’ first symphony very consciously quoted the “Ode to Joy” theme from Beethoven’s ninth, which was his imaginative way of dealing with the expectation placed upon him. The serenades, however, are deliberately much closer to Beethoven’s work, filled as they are with triplets and other motifs familiar from his work. This serenade is the real missing link between the two composers, and precisely because of that, it’s one of my all-time favourite bits of classical music:

Serenade No. 1 in D Major, 1st Movement – Allegro molto:

As well as these large-scale multi-movement works, Brahms also found time to write several more compact orchestral pieces. For me, the best of these is the Academic Festival Overture, which the composer wrote in thanks to a university after he had been given an honorary doctorate, and includes melodies taken from a number of rousing student drinking songs. Listen out especially for the joyous ending at around nine minutes in:

Academic Festival Overture, Opus. 80:

If you like that, then it’s also worth hearing the rather more sober Tragic Overture, and the groundbreaking Haydn Variations. If you prefer Brahms’ fun side though, I thoroughly recommend his series of 21 Hungarian Dances, which were amongst the most popular (and bestselling) of his works during his own lifetime. Don’t let anyone tell you these pieces are lightweight or silly – they are fantastic and deserve to be considered alongside his more serious work. They also show Brahms’ eclecticism and interest in contemporary dance music, regardless of whether it came from Eastern Europe or a Viennese ballroom. Dvorak, following Brahms’ example, later published his own Slavonic Dances, which are also brilliant. To get the full flavour of these works you really ought to listen to all 21, but here’s the one you almost certainly know already, Number 5, courtesy of Charlie Chaplin:

Hungarian Dance No. 5 in G Minor – Allegro:

However, there was another work which really brought Brahms to prominence, a piece which contained none of the frivolity or joy of his other popular pieces. In fact, it was the single most serious and sombre work he ever wrote – his German Requiem, which was produced in response to the death of his mother. In you’ve not encountered the term before, a Requiem is a mass for the dead, the most famous settings of which include those by Mozart, Verdi and Faure. Ordinarily, Requiems use a standard set of Latin words, but Brahms, being German, and culturally if not spiritually Protestant, chose instead to use extracts from the Lutheran Bible. The result is moving and original, powerful and elegiac. In Brahms’ hands the Requiem becomes a plaintive meditation on mortality, as well as an outpouring of grief for an individual loss. This is perhaps the most stirring movement of all, the title of which translates as “All that is flesh will be as grass.” It starts slowly, but a little patience is soon rewarded by a huge surge of vocal power at around the three minute mark.

Ein Deutsches Requiem, Op. 45 – 2nd Movement, “Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras”:

There’s a lot more music to get through yet, but if you want to hear more of Brahms’ vocal and choral music, I’ve included his Schicksalslied (Song of Fate), Vier Ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs) and the Alto Rhapsody in the Spotify playlist at the start of the article.

Concertina

Since it took Brahms several decades to summon up the courage to confront the symphony, he was left with plenty of time to explore other genres, and so it was as a writer of concertos that he first made his name. His first piano concerto, written shortly after the death of Robert Schumann, is brilliant, but understandably gloomy. You can find it on the Spotify playlist, but for now I want to skip on to the second piano concerto, which, if pushed, I might have to choose as my favourite concerto ever. Why do I love it? Well, every movement is permeated with Brahms’ genius, it is structurally complex, remaining unpredictable even when you know it fairly well, the piano writing is stunning and crystalline, and the handling and transformation of different motifs and themes is extraordinary. Its emotional range is also huge, at times furious and severe but, by the end, carefree and childlike. The piano seems less like a musical instrument and more like the protagonist of some epic drama, engaged in a frenzied battle with huge, uncontrollable forces. Here’s the vast first movement to give you an idea – don’t worry too much about getting to grips with every detail the first time you hear it, just let it flow over you. This is performance from earlier this year given by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. I’m pointing that out not only because every musician in this ensemble is exceptional, but also because, as the name suggests, it’s a slightly smaller orchestra than the kind you might ordinarily see performing Brahms, so they avoid they “heaviness” usually associated with him:

Piano Concerto No. 2 in Bb Major – 1st Movement, Allegro non troppo (Part One)

Piano Concerto No. 2 in Bb Major – 1st Movement Allegro non troppo (Part Two)

Next up is the violin concerto, which again, is one of the truly great examples of the form, along with those of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Mendelssohn. Just listen to the finale – there’s simply no way that this could be improved. This isn’t the best quality recording you’ll ever hear of this piece, but the sheer joy of this interpretation tells you everything you need to know – it’s just glorious:

Violin Concerto in D Major – 3rd Movement, Allegro giocoso:

Brahms frequently gave the first performances of his own piano works, but he wrote the violin concerto with another performer in mind, namely Joseph Joachim, one of the most outstanding musicians of his time. Composers would frequently leave a section of a concerto intentionally blank, so that the soloist could throw in some virtuosic variations on the main themes of the piece. This section was called a cadenza, and Joachim in particular was known for his stunning work in this area – his cadenzas often became definitive, set parts of the music, like great cover versions which outshine the originals. He was a little less successful in his private life, and during his divorce, Brahms sided with Joachim’s wife, and the two men saw little of each other for many years afterwards. In a typically Brahmsian gesture, the composer later extended a musical olive branch by producing what would turn out to be his final orchestral work – a double concerto for cello and violin. This unusual type of work was not unprecedented, Bach’s double violin concerto and Sinfonia Concertante works by Mozart and Haydn were forerunners, but Brahms’ attempt is arguably one of the most successful of its type, certainly in the Romantic period. Even Beethoven had struggled to get the balance right between multiple solo and orchestral parts in his Triple Concerto. Brahms somehow succeeded in pulling off this incredibly difficult task, and also dramatised his conflict and reconciliation with Joachim in music. Here’s the mischievous final movement –

Double Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, 3rd Movement – Vivace non troppo: