I’ll start with the obvious: everything about The War On Drugs implies a road trip, a journey, wanderlust writ large. This idea literally came to life on LIVE DRUGS, the band’s first live album, which was released late last year. The album doesn’t capture a single set, but several; each song was chosen from a variety of recorded performances as the band toured their two latest albums, 2014’s Lost in the Dream and 2017’s A Deeper Understanding. Fans who’ve missed out on their live shows – this guy included – get a glimpse into the energy Adam Granduciel and company bring to their songs outside of the studio. Fleshed out with songs from their debut album, 2008’s Wagonwheel Blues, LIVE DRUGS feels like a highlight reel of a band who, by anyone’s account, has made it, and wanted to give their fans a glimpse into the journey that got them there.

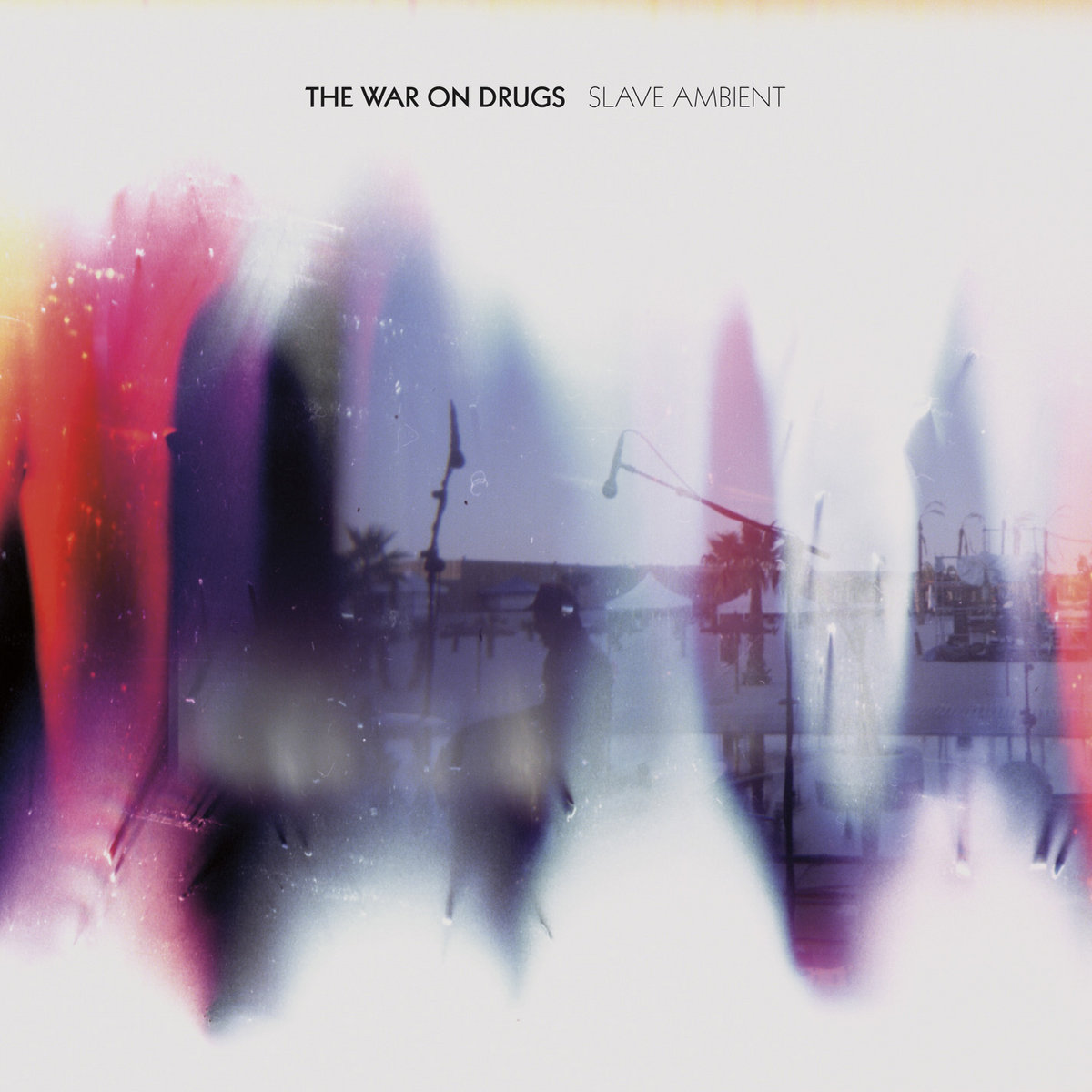

But, LIVE DRUGS has one flaw: it doesn’t include any songs from their excellent second album, 2011’s Slave Ambient, which turns 10 this month. Sure, this makes sense: their following two albums were met with critical and commercial acclaim (as our initial review accurately predicted) that catapulted them into the echelons of today’s great rock bands. Lost in the Dream blew wide open their strand of heartland rock with roaring anthems stretched over minutes of thunderous soundscapes: the album launched the band into the festival circuit and is widely regarded as their best work to date. A Deeper Understanding delivered a more polished and intimate reading of the band’s songcraft and only further solidified their reputation: the album won that year’s Grammy for Best Rock Album. As The War On Drugs amassed newer fans, I can understand that many may not be familiar with their sophomore effort.

Of course, The War On Drugs deserve all the accolades and attention from their latest albums, though none of it would be possible without the stepping stone of Slave Ambient. The album hints at the songwriting directions they’d later embrace and showcases ones they’d leave behind. It’s easily their most sonically cohesive and atmospheric record to date, yet is nevertheless filled with emotional and climactic moments. The thrill I get when listening to Slave Ambient today hasn’t changed since I first heard it a decade ago. Here was a band that seemed to taunt listeners with their seemingly face-palm obvious influences and heartland rock touchstones – Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, any song with a fucking harmonica – and then had the audacity (read: talent) to deliver an album of genuine beauty.

The first track “Best Night” doesn’t open with a sprint, but a stroll. Granduciel’s soft crooning rolls over the song’s melodies like a car on cruise control cresting hillsides. The song ends with a melodic outro – Granduciel’s playful electric guitar riffing cuts through an atmosphere of acoustic strumming, rolling percussion, samplers, and more – that would become a trademark of the band’s songwriting. Indeed, Granduciel’s vocals remain impeccably controlled throughout most of Slave Ambient; while the following track “Brothers” ups the emotional ante with denser production and heavier lyrical imagery, his delivery never wavers.

At the time, this was a new approach for him. Tracks like the Dylan-esque Wagonwheel Blues opener “Arms Like Boulders” has Granduciel hitting the top of his range, crying such biting lines like “Let me tell you, your arms are like boulders / And your shoulders are cliffs / But your head keeps rolling off.” He soon enough shouts in-between verses on the shimmering and shuffling “Taking The Farm”. Moments like these would later define Lost In The Dream, yet are largely absent from Slave Ambient – with a few exceptions I’ll get to – and, 10 years later, only reinforces an impression that this album remains to date the outlier in their discography.

Yet, Granduciel’s control, along with the album’s atmospheric consistency, hints at a central theme of Slave Ambient: the relationship between wanderlust and introspection. The deceptively simple piano melody that threads together “I Was There” perfectly reflects a longing sentiment and is complemented by Granduciel’s opening lines: “Come on, baby, hold me close / Let me do my best to both / Let me ride, let it roll.” (Side note: this song’s use of piano would be replicated to equal effect on successive album openers “Under The Pressure” and “Up All Night”.) The road trip is a quintessential American trope and, in some ways, an extension of the American Dream; regardless of your objective, you just need to work hard and have the determination to make it come true. But there inevitably comes a reckoning with the very active decision to pack up and hit the road: Was my destination what I expected? Was I able to reinvent myself? Was it worth leaving my previous life behind?

Slave Ambient doesn’t offer answers to these dilemmas but instead focuses on mining the thought processes of those who face them. Throughout the album, people come and go, reach destinations and lovers and then say goodbye, dream of cities and the heartland and home. “I ride the freeway down by the harbor / I catch a strong wind through my mind” Granduciel sings on the album highlight “Your Love Is Calling My Name” over shuddering percussion that evokes cars passing by on a highway. He’s the most direct on “Come To The City”, where his search for the place he loves leaves him with the understanding that “I’ve been ramblin’ / I’m just driftin’” (here, he also delivers the album’s few ecstatic “woohoos”). On Slave Ambient, the road trip is interpreted as a dream, a fantasy, and reaching the destination is never guaranteed. Ten years later, in a time of unprecedented inequality in the United States and where mobility is increasingly reserved for the privileged, the ambiguity of Slave Ambient, its lack of answers, feels all the more relevant.

To their credit, The War On Drugs understood that some aspects of Slave Ambient wouldn’t be necessary on future projects. Why use transitional soundscapes like “The Animator” and “City Reprise #12” when songs like “Under The Pressure” could effectively fold them into their runtimes? The explosive “Baby Missiles”, a three-and-a-half-minute song that first appeared on their 2010 Future Weather EP, feels like a War On Drugs song in a pressure cooker. The song remains a gem in-part because of its unique place in the band’s catalog. Overall, “Your Love Is Calling My Name” comes closest to creating the climactic anthems heard on Lost In The Dream.

But of course, hindsight is 20/20; 10 years ago, the continued success of The War On Drugs, though something listeners like me rooted for it, wasn’t guaranteed. And while a strong rock album, Slave Ambient also came out in a year that included Let England Shake, Smoke Ring For My Halo, and Strange Mercy. This context underscores the particular kind of joy I get from albums like Slave Ambient; not from hearing greatness, but the potential for greatness, of hearing a band searching for their voice and getting pretty damn close. This alone is an accomplishment, a reflection of a band early in their journey, and a test for listeners like me, fortunate enough to be along for the whole ride.