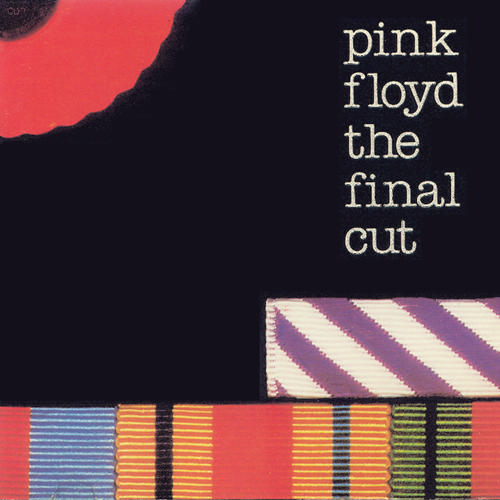

Pink Floyd songwriter/bassist Roger Waters has never been a very humble person. Whether it be dismissing fellow band members, writing a semi-autobiographical album about the hardships of his rock superstardom (1979’s The Wall), or simply taking credit for the work of others, Waters has always had an egomaniacal sense about him. By the beginning of the 1980s, Waters’ attitude had begun to wear on his fellow bandmates. With keyboardist Richard Wright being forced out of the band following the release of The Wall, and Waters’ growing sense of entitlement and forcefulness in the studio, the rest of the band began to feel exceedingly hopeless. This conflict reached a boiling point during the recording of Pink Floyd’s 1983 album The Final Cut. The sessions were notoriously heated, with Rogers refusing to give up his artistic vision, since he felt like he had compromised his vision on the band’s previous album The Wall. It was a dreary moment in the band’s illustrious history. However, despite Waters’ egomania, The Final Cut remains Pink Floyd’s most understated (and underrated) album, as well as a classic in the minimalist rock vein.

Much of the album’s weight is carried through Waters’ emotional vocal delivery, as the majority of the album is devoid of excessive instrumentation. In the opening track, “The Post-War Dream,” Waters whispers the line “Tell me true, tell me why, was Jesus crucified? Was it for this that daddy died?” over the sound of distant trumpets, his vocals reeking with anguish and an almost child-like curiosity that tugs at even the coldest of hearts. It is clear that Waters is holding nothing back emotionally. He is exposing his soul for all to see. On tracks like “The Final Cut” and “Two Suns in the Sunset,” Waters will release an exasperated wail full of pain and frustration one moment, and the next he’ll sound close to tears. This emotional ride is simply heightened by the album’s simplistic instrumentation, as the use of gentle guitar plucks and orchestral tracks, coupled with Waters’ often echoed vocals, give a sense of internal strife. It is an aesthetic that creates a shockingly intimate atmosphere to The Final Cut’s anti-war themes.

In many ways, The Final Cut feels like an album of redemption for Waters, as The Wall shows signs of artistic compromise. The band collectively decided to gravitate towards an arena rock style for several of The Wall’s tracks (most notably the songs “Comfortably Numb” and “Run Like Hell”). Waters, however, wanted the album to be stylistically similar to The Final Cut. When The Wall became successful because of these compromises and not because of his vision, Waters became resentful. He refused to make the same mistake twice. The Final Cut (which is comprised of tracks that were rejected by the band during The Wall sessions) avoids any sense of arena rock, choosing instead to focus on minimalism and subtlety. This may have alienated much of the band’s fan base, but it makes The Final Cut a more focused artistic effort than any of Pink Floyd’s previous albums (yes, including 1973’s Dark Side of the Moon).

Ultimately, Pink Floyd’s The Final Cut is evidence that beauty is an offset of chaos. In all intents and purposes, The Final Cut should have been a failure as a result of the band’s growing entropy, as well as the animosity surrounding the album’s recording sessions. Much like the album’s recording sessions, The Final Cut is a dark and difficult album. However, it is this struggle that makes The Final Cut a much more satisfying experience. In the end, The Final Cut remains a classic album and a cult favorite amongst fans of Pink Floyd – and rock minimalists alike – in spite of Roger Waters’ inflated ego.

First published November 16th, 2009