It’s 2012. The Dark Side of the Moon is 39 years old. I’m 23. Pink Floyd’s breakout eighth studio album was a hearty fifteen years old by the time I was born. For me, The Dark Side of the Moon sits along side the Star Wars Trilogy, LEGOS, and 1-800-COLLECT ads as a piece of the collective zeitgeist that pre-date any of my conscious memories. They’re all elements that seem to inhabit in an incomprehensible fog bank between pre-existence and recollection. It’s a perspective I’ll never share with some Brixton teenager who immediately dropped cash on Pink Floyd’s newest record in 1973 because he liked Meddle a whole helluva lot. Or anyone of an age with myself who made the off-hand decision to download DSofM because she’d heard syncing this Pink Floyd album and The Wizard of Oz was a great way to spend an evening with a cooked brain. Dark Side was a fixture of long car drives with my dad through rural Vermont back roads in the later hours of evening. The car’s headlamps and the clear field of stars above the only light in the world.

Unlike the toys of my childhood and the ads of the pre-cell phone society, DSofM has managed to stay relevant and personal to me – growing and changing as I continually revisit the universe that sits inside its forty-two minute run. There’s also an immersion unique to Dark Side that fosters a palpable sense of its place in my memory. As I’ve developed the critical mindset that has brought me to where I am now writing this review, it continues to be a challenge to try and approach DSofM with any amount of objectivity. For me, the climatic space battle at the end of Return of the Jedi is still the pinnacle of any and all special fx-driven awe, and similarly DSofM is gospel, written in stone as readily as any kind of moral identity I might possess and the sense memories that belong the place where I grew up. Everyone has these subjective cultural touchstones that come baked into their development and imagination and subsequent identity, and for DSotM, a record that’s sold roughly 45 million copies (the third best selling album worldwide) as it was being remastered for the second time, culturally it’s an oddly fitting place to occupy.

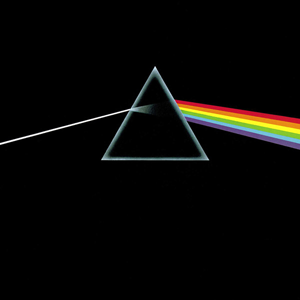

For the a large portion of my generation Pink Floyd is a group whose reputation precedes it in such a fashion as to become passe and immediately quantifiable. The latent hype of their place in the collective unconscious creates a sort of divot rot from overexposure. The critical specificity regarding the group’s place has become so well worn – not to mention associated with the enthusiasm of aging generations who obviously have no idea what the kids are into – as to create an image of undermining generality defined by classic rock station playlists that include “Money” and “Have A Cigar,” making it easy to write Pink Floyd off as “trippy” (a descriptor everyone should stop using for anything ever) as if we’ve all already heard everything they’ve had to offer via osmosis. The Beatles get this treatment. Bowie gets this treatment. Elton John. The list goes on and on and on. Where Pink Floyd differ from that shortlist is in that Roger Waters and David Gilmour are hardly household names. Pink Floyd’s image is built almost solely from iconography, mythology, stereotypical fans, and, well, music. And The Dark Side of the Moon is a bit of clarity beneath that cultural distortion.

DSotM is, arguably, the starting point for Pink Floyd’s classic era. Following a more minor breakout in 1970’s Meddle. Dark Side was the first record to sport one of Floyd’s most impactful and influential elements in a full album concept. It’s a concept album. Probably the most notorious if you’re willing to forget about Sgt. Peppers and the Lonely Hearts Club Band. In any case, it’s hard to argue that any group had committed so fully to their LP concept up to that point. Pink Floyd tied together a sense of sound design in original spoken word segments and field recordings and a move toward overt pop structure built from a foundation of gospel, blues, proto-electronica, psychedelia, jazz, and a forward vision with a lyrical concept revolving around the general human condition in its many states and effects. This is all well-covered ground.

Pink Floyd would go on to record more sophisticated and detailed conceptual visions on The Wall and The Final Cut, making goes at personal and intricate character studies and anti-war commentaries. Yet DSofM remains the group’s most recognizably Floyd-ian statement and their most immediate and accessible record. Its in part due to the broader and more general nature of Dark Side’s concept. It’s a record that seeks to deconstruct the broader strokes of humanity and there’s a relatability in the simplicity and more general outlook of its conceptual trappings. DSotM is a record that has come to define the solitary listening experience. It came out in an era where that was often times the only available option, but even in its extended legacy it fosters a quiet air of introversion. The record goes down like a pending Ambien-induced sleep teetering at the edge of in vitro dreams. DSotM isn’t so much psychedelic as it is wholly atmospheric, and it was one of the first and most approachable documents that could claim as much.

The Dark Side of the Moon’s place in the pantheon of legendary rock album legends is as a personal and individual experience, which seems to play so fiercely against type. It’s an album that captures the unconscious that connects us all both emotionally and intellectually. It’s most visceral and affecting moment is a track about death based around a four-minute outpouring of wordless vocal ecstasy and its immediately comprehensible (“Great Gig in the Sky”). In other words, it doesn’t need words. My experience growing up with the record is almost allegorical to the record’s content. That place it occupies as a classic record bubbling up through our psyche with the potential for adolescent discovery is, in a sense, exactly where DSotM belongs. There’s a short mostly inconsequential titular documentary about the album, Pink Floyd: The Dark Side of the Moon, discussing the background and creation of the album, but it ends on a memorably down note. David Gilmour is oddly wistful as he makes the point that he never had the experience of listening to The Dark Side of the Moon for the first time and that he wished he had.