“Now when you hear this on the record, I put a lot of symphony to it… I’ll be lucky if I can remember the words.”

This warning from Axl Rose, lead singer of Guns N’ Roses, preceded the first-ever live performance in 1991 of “November Rain,” a track that became a chart-topping single later that same year. (You know this song: it broke both production budgets and MTV viewing ratings for its time, and even today, in the Bieber era, it has 50 million views on YouTube alone.)

Rose’s words back then said a lot. When he declares that he, specifically, had added a symphony to the studio version of the track, and that he would be lucky to remember the words, it isn’t incidental; by this point in time, the band, for all practical purposes – at least in Rose’s eyes – belonged to him. The rest of the group was too drugged-up and complacent to realize what was happening until it was too late, musically and legally. And that distanced, fragmented nature is part of what makes the Illusion records so great: everyone’s functioning on their own level, in their own world, some of them barely hanging on. The result isn’t remotely cohesive, but it’s never boring.

Of course, it’s no wonder why the group members were doing their own thing: In 1986, on the cusp of their historic debut album, the band all lived together in a squalid townhouse. By the turn of that decade, they were featured on every magazine cover, their lives under a microscope. As bassist Duff McKagan later remarked, they went from existing as a family to suddenly having their own mansions, their own limos and their own lives.

But it was Rose, in particular – perhaps due to his overtly rebel image, or maybe just because he was the singer – who was most immediately established within the music industry, flying the world by private jet (even when the rest of the group flew together) and adorning the cover of Rolling Stone.

The yes-men were already surrounding him, whether it was wannabe writer Del James (whose short novella was a supposed inspiration for “November Rain”) or the greedy record label executives (probably the same responsible for allowing Chinese Democracy to gestate for nearly two decades). So that little seed of excess that could be heard in bloom on Appetite for Destruction (the synth keyboards on “Paradise City,” for example, which Rose added unbeknownst to his bandmembers) soon blossomed into completely overblown theatrics – inspired in part (ironically enough for an alleged homophobe) by Elton John and Queen.

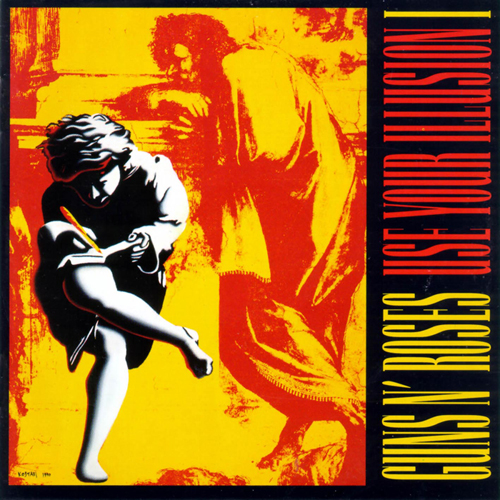

Conceived wholly as a double album but released as two separate volumes, the Illusions’ first chapter is its angriest. The record begins with the blistering “Right Next Door to Hell,” the lyrics written by Rose in response to his then-neighbor’s accusations of assault.

It’s that intrinsically personal ranting that makes Use Your Illusion so memorable. Yet Rose also has a penchant for writing in ambiguities – he obviously has specific targets in mind for some songs, but as on tracks such as “November Rain,” the general themes can be applied to anyone: unrequited love, bitterness, envy, hate, despair, loneliness, addiction. (And, conversely, that’s precisely why “Get in the Ring,” from this album’s sequel, turns into such an awful track: built upon a promising, boozy blues-riff by Slash, the song leads into an embarrassing bridge where Axl, shrouding his lead guitarist’s solo, begins rambling off a list of names: magazines, pop culture figures. Listen to this in 2011 and none of it matters; most of the people/publications named aren’t even relevant anymore. For the most part, however, UYI I is thankfully spared these embarrassing moments.)

Other bandmembers manage to take the spotlight at times. “Dust N’ Bones” features the underrated Izzy Stradlin on vocals, but the song itself is ultimately one of the less memorable here. (For what it’s worth, his solo albums have been generally solid.) Stradlin takes over vocal duties again (with Axl in tow) for “You Ain’t the First,” a tongue-in-cheek (maybe?) ballad that sounds like something cowboys would sing around a campfire. A fun track, but not really substantial enough to stand ground against some of the other material.

“Don’t Cry” achieved notoriety not just because it’s a great ballad, but because of the death of Shannon Hoon, the singer of Blind Melon. Rose and he were close friends; Hoon was invited to record backing vocals for multiple tracks on the Illusion albums, and Rose, in return, helped him achieve more mainstream recognition. The song is one of the band’s best, if you can appreciate their ballads. (It’s also worth noting that it was during the music video shoot for “Don’t Cry” that Stradlin, who bailed prior to Guns’ Use Your Illusion World Tour, first abandoned the rest of his band, declining to appear on set and instead sending along a brisk note informing Rose that he was unwilling to further cooperate unless certain terms were met. They weren’t, and so he is absent from the video.)

Then, of course, there is “November Rain.” The music video was the most expensive of all time; it hit the top of the charts and stayed there for ages, and – over the years – almost became symbolic of the band’s peak and subsequent demise. It represented the furthest removal from their Appetite for Destruction style, and is often the punchline to jokes about the group (or, more specifically, Axl – perhaps because he linked the music video so inherently to his personal life, even going so far as to cast then-girlfriend Stephanie Seymour as the bride-to-be).

But the song is simply great. For all its excess, it’s bold and beautiful and has a couple absolutely killer guitar solos. It’s been favorably compared over the years to epic rock ballads like “Stairway to Heaven” and “Layla,” and can comfortably share the same space with them on best-of lists. And Slash has pretty much built his entire brand around his iconic image from this video; it wasn’t long after this that he basically refused to ever remove his top hat.

Despite a couple softer ballads, Use Your Illusion I is, as has been mentioned, the harder, angrier and more vitriolic of the two Illusions. You have dirty, uncomfortably catchy tracks like “Back off Bitch”: originally recorded for Appetite, re-recorded here, and backed by the band’s most Stonesy riff, there’s nevertheless something both nastier and more abrasive about it than any of the spiteful or misogynistic lyrics on Appetite (but maybe that’s just because the polished production qualities clash against what should instinctively sound rawer and grittier). You also have tracks like “Don’t Damn Me,” which once again reflect the paranoid mindset of a singer who previously railed that the world was out ta get him.

And that’s Use Your Illusion in a nutshell: frustratingly brilliant. Flawed. Sprawling. Grandiose. Self-indulgent. Indecisive. Songs veer between near-perfection and utter disaster. There is not a single album in existence that perhaps sums up the perils of rock n’ roll decadence as these two volumes – you can practically hear the band rising and falling, exploding and imploding, coming dangerously close to a parody of the rock n’ roll cliché without ever fully embracing it. And with the traditional music industry dead and music stars as fleeting as the headlines they’re courted by, there will probably never be another album like it, because very few artists will be afforded the opportunity to achieve such excess.

(The review should close there. But one thing must be noted: the album’s final track, “Coma,” is also one of the band’s most underrated cuts – ever. It is both the signature sound of the Illusion records – sprawling, over-produced, overlong, bombastic – and the signature sound of its authors, Rose and Slash. Rose’s lyrics – wordy, ambivalent, vague, and borderline nonsensical in their phrasing at times – are at their most pained and introspective, and the verses after the last guitar solo are some of the most powerful he’s written. And Slash’s solos are two of his most creative and emotive. The song is a monster, perhaps not as well-regarded as it should be simply because of its long running time.)