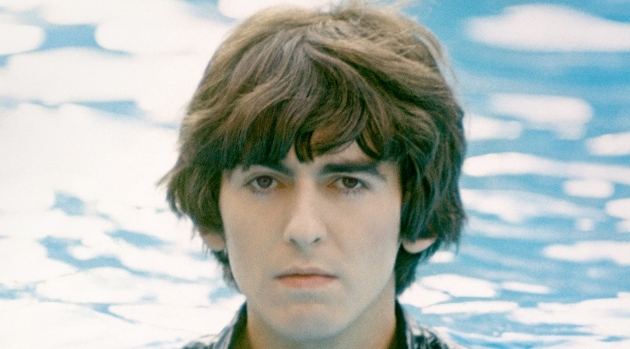

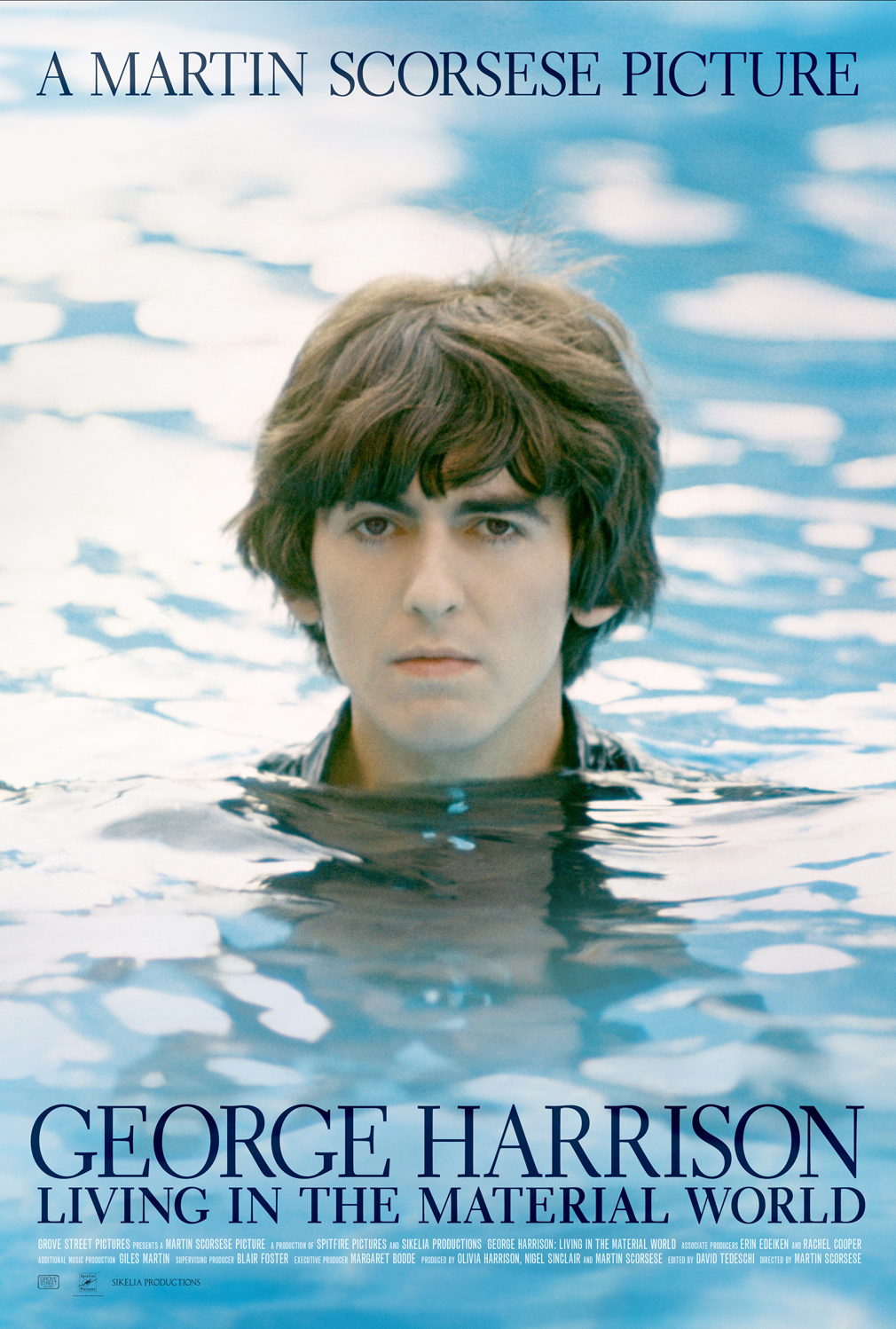

The first thing that must be noted about Living in the Material World, Martin Scorsese’s new documentary on George Harrison, is that it’s a George Harrison film, not a Beatles film. When their story, the most-told in the history of popular music, comes up, it’s only to explain the role they played in furthering, and occasionally holding back, George’s artistic and spiritual development. It’s a savvy decision from Scorsese. Even a filmmaker of his caliber probably couldn’t unearth new insight on The Ed Sullivan Show or the making of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. There isn’t an aspect of The Beatles’ career and legacy that hasn’t been exhaustively covered in at least one of the countless books and documentaries that have been produced over the last 50 years. Yet a sizable majority of the retellings of their story focus on the defining partnership between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. It’s understandable — they wrote the bulk of the songs, and it was their personality clash that ultimately led to the group’s demise. But Harrison, the so-called “quiet Beatle,” led a life that deserves to be explored not only because of his immense musical talent, but because his personal and spiritual transformation says a lot about the underlying contradictions of the free-love era.

In the film, Beatles producer George Martin points to the isolated nature of Harrison’s songwriting contributions to The Beatles as the cause of his frustrations with the group, and this holds true in more ways than one. Not only did the backlog of songs that Harrison wrote that didn’t appear on their albums serve as a cause of frustration, but Martin argues that his exclusion from the Lennon-McCartney partnership/rivalry deprived him of the friendly competition that would have pushed his songwriting to even greater artistic heights. He did fine in that department, of course — “Something” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” are two of the most beloved Beatles songs, and many of his compositions that the group didn’t use ended up on All Things Must Pass, the best album any Beatle made after the breakup. Still, the perceived limitations of his role in the band led to his exploration of Eastern religion as a form of escape and self-betterment.

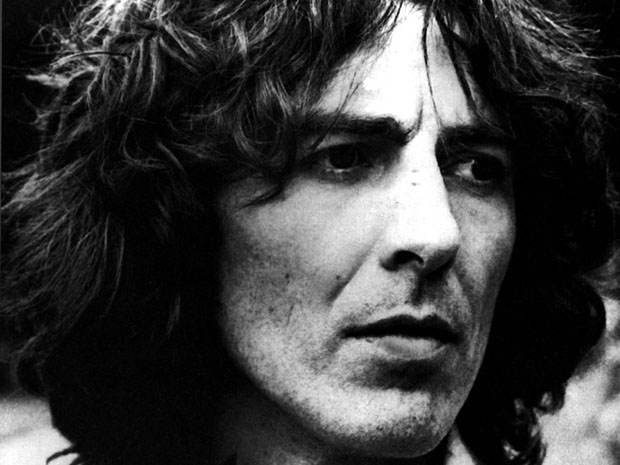

Harrison’s spiritual quest is what the bulk of Scorsese’s two-part, nearly four-hour film focuses on. All four Beatles famously visited the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1968, but the effect it had on Harrison was most profound. He had been playing sitar on Beatles records as far back as Rubber Soul, but he came to the conclusion after hanging around with Ravi Shankar that he did not have the capacity to be a sitarist. Still, that art’s influence on his guitar playing and songwriting during the second half of the Beatles’ run cannot be overstated. It represented a turning point for him, and he began thinking much bigger than being the third-most popular member of the most-loved group in the world. His future contributions to the Beatles would be more diverse and wide-ranging than they were before, but there was no chance of his finding satisfaction within those confines.

Harrison’s new-age leanings also indirectly played a role in the biggest tabloid scandal of his life. To hear friend and collaborator Eric Clapton tell it, George’s attitude about material objects and commercialism was the green light the former Cream guitarist needed to pursue Patti Harrison. He was basically right. George was furious at first (Patti’s account of the initial confrontation between the two friends and the first time Clapton played her “Layla” is one of the centerpieces of the film), but by the time of a mid-’70s interview, all was seemingly forgiven. “Eric is a dear friend,” Harrison said then, “and I’d rather have her be with him than some dope.” That’s more forgiveness than somebody who stole his best friend’s wife should expect, and it says a lot not only about the influence of Hinduism on George’s life but also the vulnerabilities it invited.

Also covered in depth in Living in the Material World is Harrison’s near-fatal 2000 stabbing at the hands of a deranged fan. The incident is recounted in unexpectedly comical fashion by his second wife, Olivia. She characterizes it not as a contributing factor to his death in 2001 but instead as an opportunity for her and George to work out the remaining kinks in their marriage before it was too late. George’s son Dhani, meanwhile, contended that the stabbing expedited his father’s death at the hands of the lung cancer that had been diagnosed some years previously. By all accounts, George handled death as gracefully as one can. It was the final chapter in a misunderstood, fascinating life.

Of course, Living in the Material World excels under traditional rockumentary parameters as well. Scorsese and HBO rounded up every heavy-hitter you’d ever want interviewed — Paul and Ringo, obviously, as well as Clapton, Yoko Ono, Tom Petty, Jeff Lynne, Astrid Kirchherr, and countless others — and were granted full access to Harrison’s video and audio archives. There’s plenty of porn for Beatles nerds in the form of unseen photos and footage of Harrison in the studio (highlight: George isolating vocal harmonies in “My Sweet Lord” and “Awaiting on You All” from the All Things Must Pass multitracks). Given the subject and director we’re dealing with, there was no way this documentary wouldn’t have been worthwhile. But the amount of fresh perspective and insight Scorsese is able to wring from this well-covered territory makes Living in the Material World an absolutely essential addition to the Harrison canon, as well as those of the Beatles and pop music as a whole.