I Just Saw is a new series of personal essays regarding the live concert experience. Rather than our full live reviews, these will be presented without photos and will be entirely colored by the personal experience the writer had at the show.

I recently had the rare pleasure of witnessing a performance of Arnold Schoenberg’s opus 21, “Pierrot Lunaire.” The concert was put on by the German Society of Pennsylvania, and the performers were the very adept faculty of the University of Delaware’s Music Department. The space was gorgeous, and as is apt to happen when one attends a performance of a rather hard to digest piece laden with dissonant violin squeals and general abuses of the instruments the audience was so sparse that it almost felt as if it were a private performance.

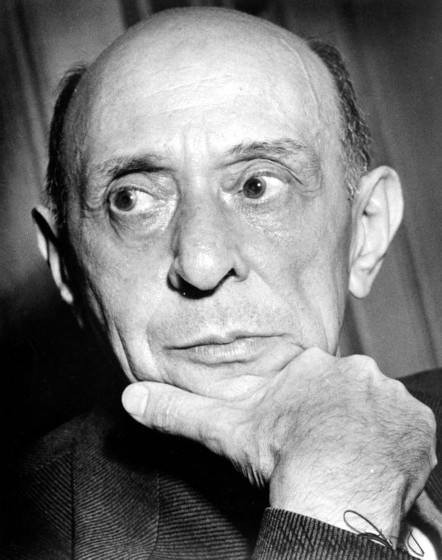

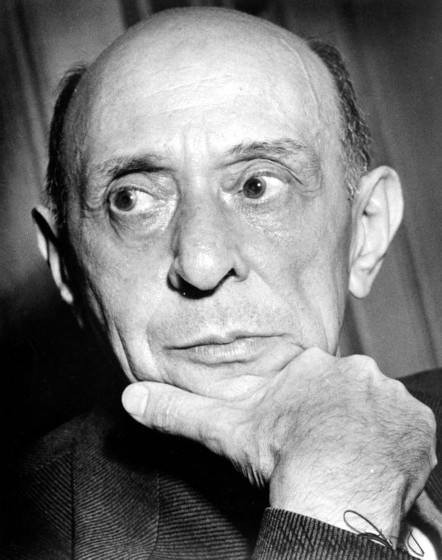

“Pierrot Lunaire” stands out amongst Schoenberg’s pieces as one of the most essential to understanding his music, although I am certain that he, particularly in his legendary arrogance, would scoff at me for spouting such simplistic blasphemy. The piece is his 21st opus, contains 21 poems, all of which utilize the same line on the first, 7th, and 13th lines. The poems are divided into three sets of 7 poems, and as previously mentioned, each poem finds itself divided into three sets of seven by virtue of the line repetition. The poems were written by Albert Giraurd about 20 years prior to the pieces composition, and tell the story of Pierrot’s musings on God, sex, and death, and his eventual shame in his existence, all while poking very dark fun at the seriousness of such contemplations. The piece rarely breaks into a cohesive melody, at least for one who has not had the fortitude to study it, and the musicians are forced into a limbo of sorts, wherein the are all soloists, yet also parts of a chamber orchestra.

As such, performing “Pierrot Lunaire,” and really any Schoenberg, except for his earliest and latest periods wherein he shies away from his obsession with numerology and returns to more traditional forms, is immensely challenging and one has to approach listening to his music with no small generosity. That being said, it needs to be performed correctly, and is certainly worth the effort required for the emotive qualities conveyed by his compositions are inimitable, as he treads the fine line between complete disorienting chaos and spectra beauty.

I am pleased to say that while this performance will probably not go down in the books as one of the great achievements in performing Pierrot Lunaire, justice was done to what is billed as one of the ‘quintessential pieces of the 20th century’. The performers displayed the vitality and courage that the piece requisites, and the singer in particular. Her part is particularly difficult, as she is singing the thoughts of a man (and a misogynistic one at that), and has to switch seamlessly between squealing vocal paroxysms and thoroughly disconcerting whispers all while keeping time in a piece that often feels like it has no meter to speak of.

The onset of the performance, or any incarnation of the piece, conjures the feeling of being dragged very slowly into a frigid body of inestimably deep water. One waits for a cohesive melody to form, something that the mind is able to grasp with some sense of ease and pleasure, something predictable. This will not occur; all you will find is ephemeral spurts of atonal notes. The key to listening is exactly the same key to swimming in hyberboreal water: accept the discomfort, discoporate, and remember why you got in as you immerse yourself in the scrotum shrinking darkness.

After you have developed resistance, the appeal of the music sets in. It’s harsh, it’s eerie, and you look at your program (complete with an English translation of the poetry), and know you are consuming something that does not glorify the human experience, but in fact paints it as the internally contradictory and pathetic light in which it actually exists. The various shrieks and proto growls emanating forth from the singer’s mouth in the ferocity of the German language in all its guttural glory speak to an animalistic understanding of terror and disgust that cannot be conjured from other mediums. I would venture to say that other attempts, particularly those that learned a great deal from Schoenberg’s musical philosophy, sound banal, trite, and inauthentic.

Listening to this piece, I found it difficult to decide whether to watch the performers or not. The part of me that enjoyed admiring the technical requirements of the piece was compelled to observe exactly what was necessary to create this perfect dissonance, part of me simply wanted to be washed over in grating yet perfectly organized sound. To illustrate my conundrum, at one point, the clear focus of the music was the cello player, who was on the verge of breaking the strings due to the ferocity with which he took to sawing away at them. His line sounded like the rusty gears of a diseased machine, and it was by watching him I realized how truly revolutionary the piece was. The techniques he was employing are just starting to make their way into modern non-classical music, from extended harmonics to percussive elements that are being experimented with by guitarists. Here I saw that these ideas had been written down on sheet music and perfectly integrated into a moving line that any (albeit extremely well endowed) cello player could reproduce.

I enjoyed the performance immensely, and the extended applause of the minimal audience made me feel even more comfortable with my appreciation. On the whole, I let feeling fully satiated, enlightened, a little bit disconcerted, and more than a little bit superior to all those who had not been listening to it with me. And I am pretty sure that is exactly what Schoenberg would have wanted me to feel.