“When the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past.”

– Mark Fisher.

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

– Antonio Gramsci.

The factories of steel and blood are churning, as states slide into warfare and political factions face polar turmoil. God is dead, and it’s the end of history. Gender as we’ve known it is melting and money’s losing value.

And this is the sound of the moment:

– the industrial hammering of beats – the distorted screeching guitars resembling deadly machinery – manic, frenzied mantras in style of monologuing institutionalised patients – a bass which, somewhere, looks for some sort of lost system – crackling samples and distant foliage –

2023 saw the climactic release of a number of albums from groups with diverse backgrounds and histories, united in the interest for a new, mechanical sound that abandons generic conventions, thus mystifying critics as how to classify this style, see-sawing back and forth between inadequate translations such as ‘post-punk’, ‘metal’, ‘industrial rock’, ‘neo-no wave’ or ‘post-techno’.

This has led to the need to imagine a new (sub)genre terminology, which adequately summarises this style, and the bands which can be aligned with it. These groups are, in alphabetical order: Gilla Band + Mandy, Indiana + Model/Actriz + Naked Lungs.

Embodying various elements of post-punk, techno, no wave, industrial, noise and metal as origin points, while still angular and defying the standards of the marketable and gentrified guitar-sound that defined the indie-era, Futurismus possesses a genuine and distinguishable aura, even with the usual shifts in process with each band (which of course can be observed in all sub-genres).

In this text, I will look at the sound of the moment, via the patrons of a new (sub-)genre, which hereby is defined as: FUTURISMUS.

I. I’m not sure that I’m alive when / I picture what it means to die – The death of imagination

In his extensive writing, the late great Mark Fisher argued that society had lost its potential to imagine a future beyond the now.

Fisher saw the loss in this interest as a direct side-effect of our everyday experience with materiality. Where, in the past, we dreamt of magical objects which would transport us – such as spaceships and Star Trek‘s ‘Beamer’ – imagination soon led to a betterment of the very appliances we held – flying cars. Video-Phones. Soon, as some of these distant objects came into being, our imagination was only able to produce strings of adjectives for what we already had. Faster cars. Smaller phones. Larger monitors. Innovation only existed to provide inside-appliance updates, which helped corporations to insist on manufacturing cycles: your old iPhone might be swell, but the new one is slightly larger, and it’s green. The one after will be smaller, with a better speaker, and back to black. Everything is an update. Soon, we forgot to dream.

With capitalism and neoliberalism becoming the steering ideologies of modern culture’s industrial complex, the very forces in control of promoting art as well as producing and shipping physical media slowly but gradually morphed into corporate mega-structures, where the finished is as much a branded product as the creator. Assimilating the ideology-drenched aesthetics of DIY movements such as punk, techno, metal and hip hop, effectively rendering their political message into fashionable accessories, and gobbling up smaller entities in the process of imperial business ventures, these mega-corporations found themselves in a crises when, by the late 90s, affordable internet connections allowed for a rise of ungoverned virtual spaces.

Just as piracy became a household philosophy, and Radiohead’s Kid A and Amnesiac proposed the imago of a liminal space beyond Cyberpunk fiction, a wave of retro-styled guitar rock shattered the modernist thinking proposed during the past 25 years. The sudden nostalgia for a DIY ‘garage-like’ sound, coupled with a burgeoning interest in physical media of the past (such as cassette tapes and vinyl records) was an easy fix for the marketing cycle. As ‘indie’ became a stylistic genre-descriptor, instead of label classifier, critical imagination towards descriptors for these sounds tanked. The Strokes, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Franz Ferdinand, Bloc Party, Deerhunter and Liars were deemed, respectively, ‘The-Bands’ + ‘Garage-Rock’ + ‘Retro-Wave’ + ‘Post-Post-Punk’ + ‘Wave’ + “Art-Rock’. It’s been like this, ever since.

Any new guitar-based album is quickly classified into a marketable niche that, itself, is based on the consumer’s nostalgia for the bands of their youth, and the genres they inhabited. In the process, not only did the culture lose a thirst for a new terminology to reflect change, it also effectively eradicated the desire for change of the pre-existent sounds: for that cannot be, what we can’t imagine.

Thus, as Fisher argued, new sounds would be inspired by “a nostalgia for all the futures that were lost when culture’s modernist impetus succumbed to the terminal temporality of postmodernity.” Writing on Hauntology, especially in the occultism-tinged spectres of British landscapes present in electronic music (such as Burial and the Ghost Box label), Fisher tried to define their inherent nostalgic qualities as “a formal attachment to the techniques and formulas of the past, a consequence of a retreat from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms adequate to contemporary experience.” Given that the sound of these ‘hauntological’ compositions is so often defined by the very production methods of electronic music, so manipulation of electronic instrumentation and inclusion of sampling or intentional sonic decay (i.e. crackling to signify a degrading physical medium), its very aura instills a sense of lost presence that guitar-centric music lacks: there’s always a band behind those instruments. Thus, a new genre can only blossom once it embraces a modernist approach to master the challenge of innovating the form. As capitalism and neo-liberalism has enforced corporate overreach as an acceptable status quo, anything ‘new’ can only rise as a direct repudiation of its very ideologies. Seeing how mainstream labels used the terminology of alternative groups to market progressively more gentrified configurations of nostalgia-mining pop-rock, this aesthetic would have to evolve from a variety of subversive ideals and confrontational sounds, the way they were before the taming.

II. With a Body Count / Higher than a Mosquito – Futurism and the human body

There’s a cyclical form to everything: the interest in submerged political ideologies – the desire for esoteric spiritual thinking – the ebb and flow of peace and something worse. Our current day is not too different from 100 years ago – the opening lines of this essay could just as well summarise the 1920s. In both decades, decadence would come to define artistic movements that struggled between ascetic political realism and emancipatory decadence. Now, as then, centrism reclined to give way to the rising popularity of ideologies on the left and right of the political spectrum. Empires would find themselves in turmoil, as wars had become the defining bookmarks to the developmental process of the European landscape. And money was uncertain, with inflation becoming a common factor of the everyday and produce disappearing from the shelves – capitalism seemed in its late stages.

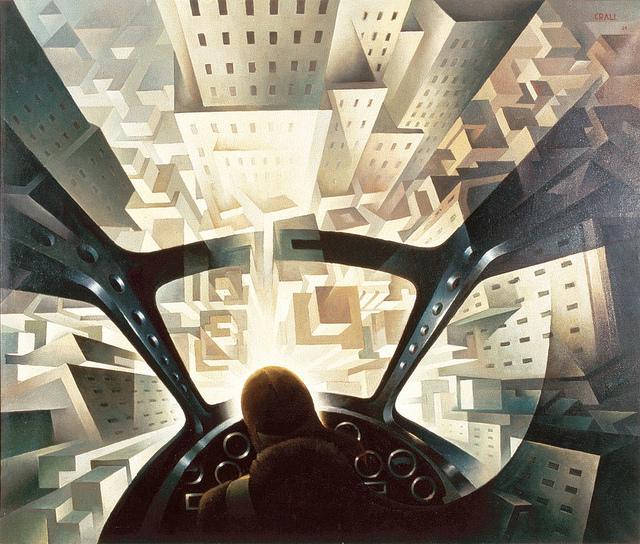

In this era of upheaval, at the birth of the 20th century, the art movement billed Futurism took shape. Emerging in Italy and Russia, the works of the Futurists were classified by a constant sense of dynamic movement, evolving elements from Constructivism, Dadaism, Cubism, Surrealism and Art Deco. Ideologically, the Futurists committed themselves to a constant quest for progress, which would manifest itself in the development of its art form, and the celebration of speed, machinery and industry.

But reading Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s 1909 released manifesto, there’s also an ominous martial tone, which celebrates war itself and – bizarrely, as many Futurist artists were women – decries feminism. Preceding the defining moments of the 20th century, and negated through the ideological and political perspectives of many of its followers (as so often with artistic manifestos), Marinetti’s text stands as much a document of his individual mindset as it provides insight into the chaotic dynamics of this period. As Italy was overtaken by fascism, dozens more manifestos followed, proposing a “universal dynamism”, and in turn imagining complete dehumanisation in favour of an incessant forward rush: “The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten four three; they are motionless and they change places. […] The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their turn the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it.”

Abandoning its more reactionary tone, investigating the works that it inspired – especially in painting – in other countries and from artists with more left-leaning politics, we are left with the surreal parallel identities of machines and human bodies, crystalline cityscapes and busy movements, celebrations of machines which seemingly fuse with the human body in an almost Cronenbergian way. With the decades, as Futurism evolved past its origin story and beyond fascist association, artists like Tullio Crali, tried to evolve it to new perspectives which defied Futurism’s cynical post-humanism in favour of more poetic, spiritual language: “The changing perspectives of flight constitute an absolutely new reality that has nothing in common with the reality traditionally constituted by a terrestrial perspective […]. Painting from this new reality requires a profound contempt for detail and a need to synthesise and transfigure everything.”

Even as it moved past its disgust for humanism, Futurism still found language to express its contempt and disgust in the mundane of whimsy, activating poetic, dream-like structures.

III. Ce n’est pas une révolte, c’est une révolution – FUTURISMUS

Rooted in stark leftist viewpoints, Futurismus leans towards inherent machine-like industrial sound structures, with instruments resembling the clatter of machines more so than the grooves of disco or the jazz figurations of post-punk. Accompanied by often anguished vocal performances which portray protagonists on the verge of madness, it imagines city-scapes as nightmarish liminal spaces, chaotic hellscapes or disembodied entities which, in itself, consume the very people who built it.

In this transfiguration of the unconscious into architecture – both sonically through textures and lyrically – and the transformation of musical structures into machine-lake noise, Futurismus generates a sense of foreboding terror and ominous dehumanisation. This merging of man and machine, united in a lurid forward movement into one corporeal entity, functions as emancipation of the unconscious battle of the subject with late-stage capitalism, not dissimilar to how Industrial music in its early figurations was a damning indictment of its uncanny imagery. Linking its themes to that of the art movement Futurism, Futurismus both hints at the inherently political protest works of german painter George Grosz, such as “Die Explosion” (1917) and “Das Begräbnis” (1918), but also adds a counter-intuitive and ominous “us” to its tail end, signifying a shared experience of turmoil. In this way, it inverts Futurism’s enthusiasm for the modern world and dehumanising philosophies into a deeply humane critique of the industrial mechanics of oppressive systems and cannibalistic ventures. In this, Futurismus constitutes a new, exciting counter-cultural aesthetic.

The origin point of Futurismus is hard to pinpoint, but a noteworthy cataclysmic occurrence of its sound can be traced back to Daughters’ “City Song” and its opening lines: “This city is an empty glass / Words do nothing / No one sleeps”. The song slowly builds itself into the noisy paranoia of industrial hammering, chronicling nightmarish HR Giger-like visions of an urban machine-hell that has lost all sense of human servitude and consumes its inhabitants. With the problematic history of its creators now well known, the associations and implications behind the stark, cold, brutal lyricism are obvious, but it’s noteworthy to document that this song marked a sudden and violent burst in a landscape still defined by relatively familiar ‘indie rock’ textures, causing awkward attempts to liken this sound to grindcore or industrial metal.

The following years saw an explosion of the so-called ‘Windmill scene’, and with it a new interest in British groups who married interests in avant-garde compositions with post-punk aesthetics, finding genuinely exciting and at times prog-rock-adjacent forms of expression for themselves. The widespread success of Black Midi, Black Country New Road and Dry Cleaning has opened the door for more vitriolic aesthetics to enter the discourse.

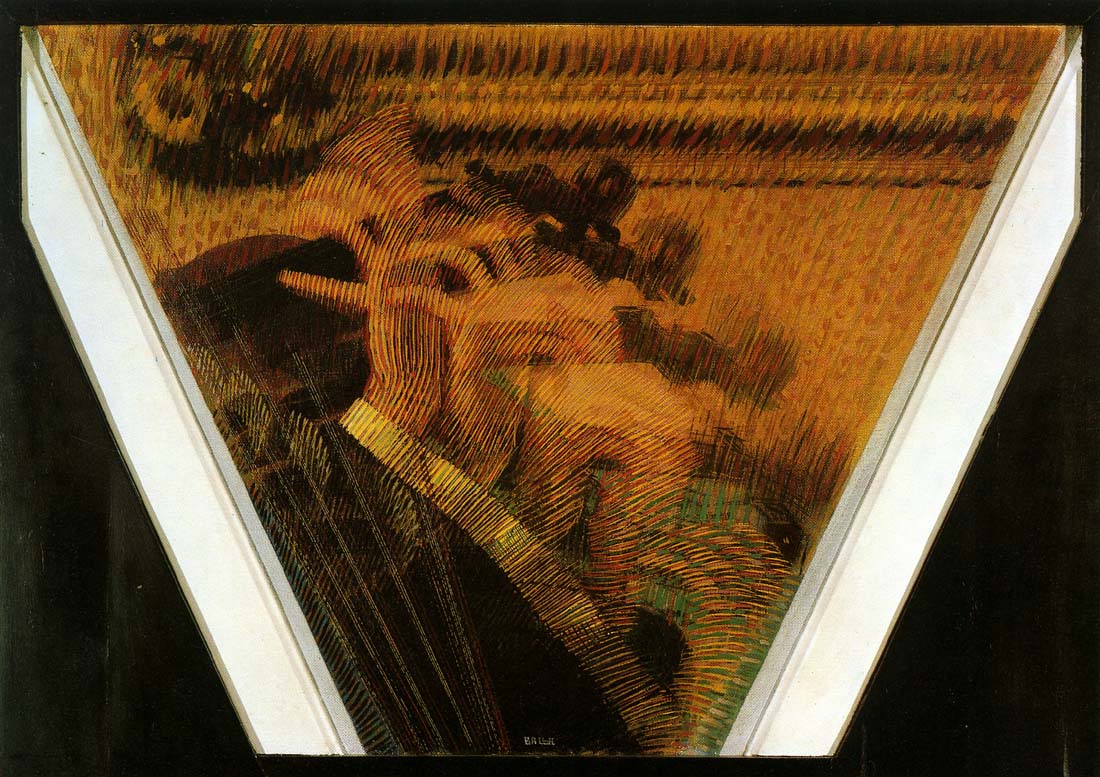

Gilla Band’s The Talkies precedes this wave. Released in 2019, the Irish quartet’s record features a unique, rhythm-based style of post-punk, which resembles This Heat’s jazz-influenced compositions, but is less formless, more clearly defined in its many sonic alterations. Where This Heat famously tried to replicate the sound of a record player breaking apart (the scratching of a suddenly broken needle, the immediate disappearance of sound into silence), The Talkies replicates the constant repetitive cycles of a machine.

“Amygdala” repeats the same strict two-second punk-loop the entire duration of the song. “Going Norway”’s tinfoil drums and humming bass make way for shrill guitar tones, effectively reconstructing the machine-room sounds of a derelict factory, while “Shoulderblades”’ cavernous, echoing tone and dry beat imagine an apocalyptic techno club. Over all this, Dara Kiely’s voice rises, alternately shrieking in pain and slurring like a drunkard – a madman whose words make no sense, constantly monologuing about imagined enemies and posing nonsensical questions. Nonetheless, there is something inherently political to his poetry, which merges working class images with body horror: “And why is the death so alive? / A cough engine / Bitter, stale / Or better: steal a belter” – “It said, “Hello” / It was dead / Feet on an armchair, sharing a head / And headache Two-face” – “Now it’s all Dutch Gold / Orange door hinge, temples grow tunnels / The first mate sunburnt at stake / Suffering sideways”.

Their 2022 album Most Normal intensified these elements. Embracing noise music, the compositions here lead with an even more merciless industrial tone, such as breathless opener “The Gum”, the searing segue “Gushi” and manic “I Was Away”. Kiely’s protagonists speak clearer now, but seem to have merged with their demons on the physical plane, such as the character whose identity is solely defined by a mechanically recounted list of cheap clothing brands he shops: “I spent all my money on shit clothes, shit clothes / I went to Unique / I went to Debenhams / I went to Spar / I went to Eason’s / I went to Aldi / I went to Lidl / I went to JC’s / Get my bootcut jeans”. The clothing brands become interchangeable and merge as the protagonist vanishes behind them, just as the narrator of “The Weirds” finds it impossible to interrogate his own transgressions: “A kind of cool word for savage is beast / But the thing I hate the least is the love of hating me”.

This tendency of constantly vanishing boundaries is especially clear in the schizophrenic “Post-Ryan”, where social turmoil becomes synonymous with dark wordplay – the hell of being homeless a dark punchline: “Took it all for granted / Gonna end up homeless / I hid behind the surreal / I’m a bit too much […] And I said I lived in a tent / In my back garden / To anyone who’d listen /In a tent for attention“.

Both records propose an intersection between soulless dance music – meaning: body music that eradicates anything spiritual – and a wandering mind that can’t find a coherent expression, or emotion, scattering between fearful anguish and acidic self-deprecation, mirroring the self-humiliation of Hubert Selby Jr.’s “The Room”.

This expression of the unfiltered unconscious, forced by the beat of its environment so it can’t ever stand still, is also present in Dogsbody by Model/Actriz. A more radical imagination of the body as disparate object, its queer idea of sexual travelogue – both of places, other bodies and figurations of relationships – merges it with food (“ Frothed milk, honey butter in my / Fortified cherry reduction / Over cakes, après-dîner / Cheers to engraved, heirloom, crystalline stemware”), the elements (“I remember pacing blank ground / I remember thorns shredding my palms / I want to see the petals stagger onto me / See my body carried, splintering / And I remember scorching it all”) and the city itself (“And through the window, reaching / I feel the morning hesitate toward me / Every day, every day / The sun turns slowly over me”). The ongoing movement by the protagonist, embodied by vocalist Cole Haden, is highlighted by the elliptical structure of the record, as its last note sueges back into its first to loop its narrative into a moebius strip.

As with Gilla Band, Model/Actriz find a pounding, clattering rhythm section that oftentimes seems to stretch the abilities of the recording process to distortion, while the guitar follows its own strange logic of high pitched, screaming, metallic notes. Somewhat related to New York’s dance-punk scene of the 2000s, Model/Actriz do fully deny the ironic nostalgia of those groups, which often pivoted to funky cowbells and campy disco references. Their vision of techno, as heard on “Amaranth” and “Pure Mode”, eludes humans completely. While definitely embracing dance qualities, their tone is of a libidinal brutality, which resembles the abject corporealities of Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo.

This vision of post-human existence also translates throughout Mandy, Indiana’s i’ve seen a way, present in the liminal space of ‘Dream Pool’ cover art by Jared Pike and the disembodied voices that vocalist Valentine Caulfield performs. Those examples include “2 Stripe”, “(ノ>ω<)ノ :。・:*:・゚’★,。・:*:♪・゚’☆ (Crystal Aura Redux)” and “Injury Detail”, where Caulfield’s mechanical way of speaking indicates an anonymous entity communicating over loudspeaker or an artificial intelligence announcing rules of décor. This is in stark contrast to the anguished screams of “Iron Maiden”, the demanding militant tone of “Sensitivity Training” and monstrous hissing of “Peach Fuzz”. A distinctly political work, the record transports its beats into caves and crypts, where drums were recorded, toying with the sonics of ‘haunted’ spaces (Caulfield’s yelps during “Peach Fuzz” were video-recorded by her in a mall – another type of haunting) and cloaking their intentions by singing in french.

Processing its guitars to a point where they turn to the sharp hissing of steam-vents, the majority of the songs are led by synthetic tones that are hard to classify. At times, the musical textures reach such an intensity that i’ve seen a way resembles the documentation of wandering abandoned alien structures, where the music fits an unclear purpose, but affects the physical state of the archeologist.

During our conversation earlier this year, Caulfield clarified that the band prefers the term ‘experimental’ as a classifier, as they find restrictive genre terminology too limiting (the writer apologises in advance) – she did expand though that there is a clear reconfiguration of music as performative vehicle, which allows her to embody a wide spectrum of personal expressions, often fed by revolutionary ideas and an angry, at times even violent confrontation with the current status quo. In this way – like its relatives Dogsbody and Most Normal – it expresses the body as a vehicle for revolutionary dynamics.

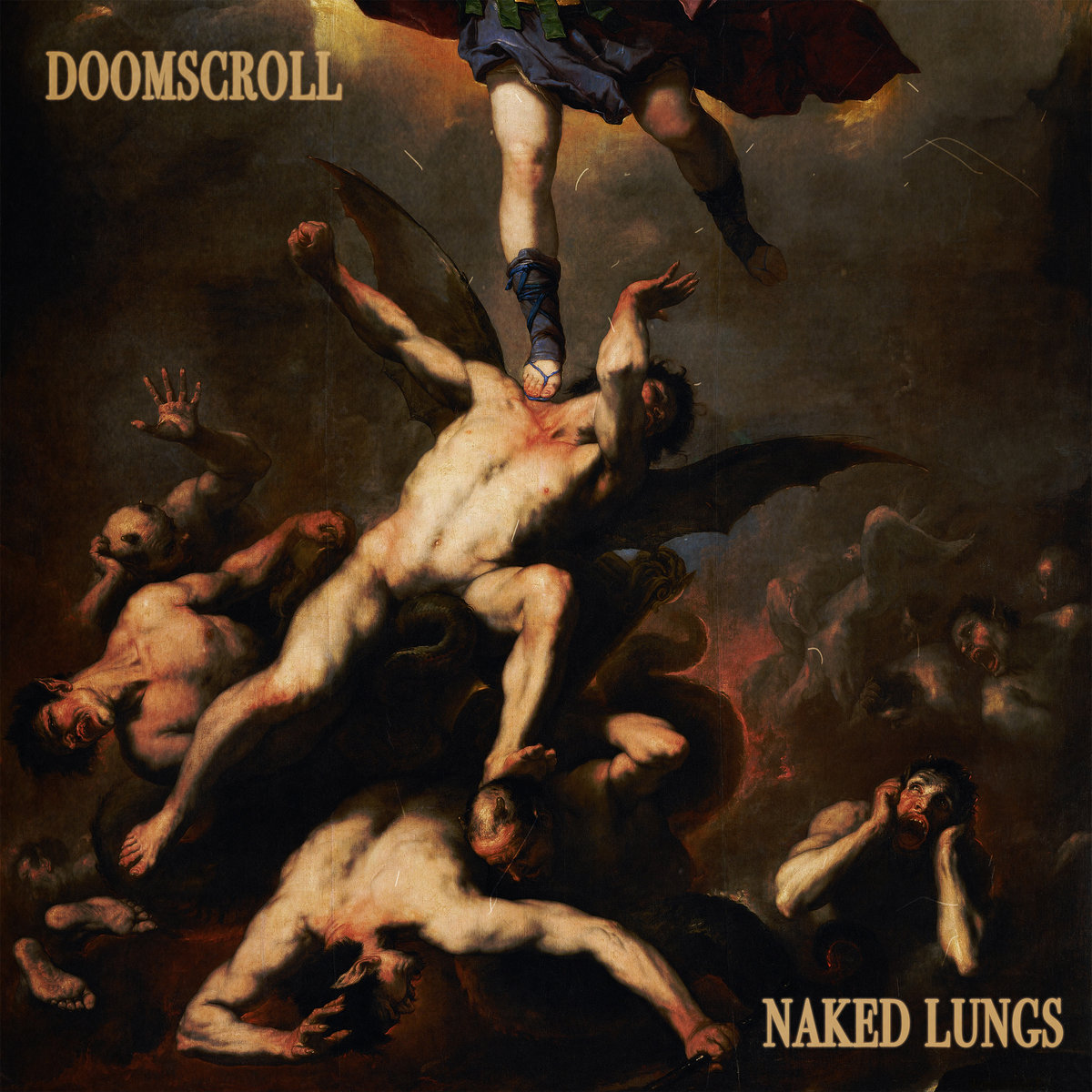

Doomscroll is more pessimistic. Naked Lungs’ debut, produced by Gilla Band’s Daniel Fox, depicts a lurid pandemonium: the everyday grind strangulating any form of individual identity. From the dark commute to work in “Gack” (“Cracked glass, expanding levels of silence / Vibrate from the understated, never fading excitement / Come close, sing a shallow hymn on the passing winds, pretend it takes you in”) to the merciless existentialism of “Relentless” (“Bone upon bone / Hazardous breathing / You’re on your own, your eyes they mislead me / Empowered by living, but what is the cost, / To live in the moment, when death always stalks”), Doomscroll portrays characters that rot from the inside out. Both the most traditional but also most lurid of the albums classifiable as Futurismus, it contrasts the inner landscape with sharp observation of the outer landscape, colliding in images of burning red rivers (“River (Down)”) and witch-hunt mob violence (“Shell”).

Vocalist Tom Brady pushes himself to the outermost limits, at times reducing his calm tone into the howled tone of a rabid animal, while guitars reach the brutal metallic ferocity of church organs, and the rhythm section transforms into the pummeling staccato of a heavy metal group. Characterised by an interest in the history of transgressive art and rich in confrontational figurations, Doomscroll‘s manic madness inherent to a cityscape that folds in on itself parallels Dogsbody, while its political interest in the unconscious as a battlefield for abyssal empowerment resembles i’ve seen a way. Yet it is more grotesque than both, hinting at a monstrous quality, a moloch beneath the thin veil of civilised reality, similar to the sudden transgressive explosions of violence in Gaspar Noé films (which influenced some of Naked Lungs’ artwork and music videos).

Each of these four groups proposes, in their own way, counter-positions to a destructive culture. Model/Actriz understand the process of libidinal transfiguration as transcendental journey. Gilla Band imagine the individual as mad hatter, free to speak truth in the elaborate, seemingly insane ambiguities of a drunk. Mandy, Indiana roleplay both sides to ensnare the ghosts of oppressive thinking, hiding deeper meaning in plain sight. And Naked Lungs turn the everyday commute into a parallel reality of walking corpses and fiery rivers of blood.

Their embattled cries rise over the gross ear piercing screams of machine-gods. Not all is lost. Rise!