Eau Claire Memorial Jazz I feat. Justin Vernon

A Decade With Duke

[Jagjaguwar; 2009]

To fans of Justin Vernon, it would seem that much of the harsh criticism he’s received is derived from his too-lovable nature. With Bon Iver, he’s put together emotionally in-touch songs while staying honest to his own tastes. He’s been Good Guy Justin in speaking out his problems with the music industry (read: the Grammys), and he has a well-documented history of supporting other musicians: the big sound on his second album, Bon Iver, Bon Iver is really a product of of such. These are things that generally make us feel good about Vernon receiving all of the acclaim he has.

But here’s a feel-good story that also became a great (and terribly overlooked) live album. In 2009, ten years after graduating from Memorial High in his home state of Wisconsin, Vernon returned to play alongside the more-than-capable school jazz band in a fundraising show. The result, A Decade With Duke, boasts several highlights and alternates between reworked For Emma, Forever Ago tracks and jazz classics. Most notably, at the end we get treated to an emotional cover of Mahalia Jackson’s “Satisfied Mind” that the fragility of Vernon’s falsetto makes invaluable. Whenever you hear Vernon mention first moving towards his near-exclusive falsetto vocal style after attempting to sing “some Mahalia Jackson cover,” you can safely assume that song was “Satisfied Mind.”

– Weston Fleming

The Gerogerigegege

Tokyo Anal Dynamite

[Vis A Vis; 1990]

The Gerogerigegege were a harsh noise group based out of Japan, and, to put it lightly, they were extremely weird. I don’t mean “extremely weird” in merely the “Damn, their music’s way out there” sense. They transcend that definition – their live shows were marked by a choreographed masturbation routine, and they released an “album” that was an octopus tentacle in place of a cassette. For real.

Their most renowned release is Tokyo Anal Dynamite, a live record that they put out themselves in 1990. 75 tracks crammed into 35 minutes, almost every “song” is an ear-piercing blast of over-amplified bass and arrhythmic drums, usually ignited by frontman Juntaro screaming “ONE TWO FREE FOUR!” Imagine any given grindcore band recreating the noise classic Naked City. Now imagine the volume turned up to infinity, and you’ve got a faint idea of how impossibly abrasive this thing is. Tokyo Anal Dynamite is overwhelming and completely inaccessible, but that’s what makes it so alluring to me; the album captures a manic live performance by one of the most extreme bands that will ever exist. If you’re a fan of noise music, you just can’t get much better than that.

– Jay Lancaster

Hawkwind

Space Ritual

[United Artists; 1973]

Space Ritual works as an even more realized concept album than it does a live album. Hawkwind get lumped in with dorky prog bands of the early 1970s (not entirely unwarranted), but musically they had more in common with three-chord protopunkers like The Stooges and MC5 and German krautrock visionaries like Ash Ra Tempel and Amon Duul II. Of course, the British outfit had little of the respective nihilistic and revolution fire of those Detroit groups, nor the aggressive, mind-expanding experimental tendencies of the aforementioned German bands.

Hawkwind instead found motivation in their visceral search for sonic communion with the cosmos and astral-born, music of the spheres philosophies and the writings of science fiction author Michael Moorcock who wrote lyrics and poems for the the band. It all sounds a bit hokey, but, thing is, it all kind of works. The record opens with what sounds like a starship countdown before the group launches into “Born To Go,” David Brock’s guitar roaring like the ship’s rear exhaust. In between some metaphysical, tongue-in-cheek yet sincere poetic musings and chugging electronic interludes, the group stretches some psych punk freakout jams across a good ninety minutes: extended mind-addling guitar and sax solos, the virtuoso thrum of a young Ian “Lemmy” Kilmister’s bass, and drummer Simon King’s constant downhill plunge.

– Will Ryan

Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic

Symphony No. 9 (Mahler)

[Deutsche Grammophon; 1982]

In a sense, all classical recordings are live recordings, but some are more live than others. What unites them all, however, is the presence of the conductor. To the untrained eye, orchestral conducting just looks like a guy flailing his arms around. Classical experts will tell you, however, that it is in fact … a guy flailing his arms around. Conductors actually fulfil a function somewhere between a drummer – keeping time – and a producer – controlling volume, sound and interpretation. Having a good conductor lead an ensemble is like getting Brian Eno in to help you with your album – musicians have to raise their game and the overall sound can be utterly transformed. Herbert von Karajan was one of the most prolific, ambitious and brilliant conductors of the last century, equally at ease with opera and orchestral works, and many of his recordings are still taken as benchmarks today.

There was, however, one weak spot in his output – the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, a composer who was himself one of the pioneers of modern conducting. Mahler died in 1911, but his works only began to be fully revived in the ’60s, by which time Karajan was a fairly established figure in the classical world, and somewhat reluctant to embrace the Mahler renaissance. Karajan’s ambivalence towards the Nazis, combined with Mahler’s Jewish background, also presented certain difficulties. But towards the end of his career Karajan began to record more of the composer’s works, in order to keep up with their growing popularity amongst listeners. This recording, made in Berlin in 1982, has come to be regarded not only as one of the conductor’s greatest achievements, but also as a definitive recording of Mahler’s last completed symphony.

Mahler’s music is, almost without exception, vast in scale, so if you’re not too familiar with his work, or classical music in general, I recommend listening to the shorter second and third movements, as they are a little easier to digest on a first listen. Or if you’re feeling adventurous, try listening to all 84 minutes in one go – listen out in the first movement for the “Farewell” motif, which either quotes Beethoven, or predicts Miles Davis, depending on your frame of reference.

– Jack Spearing

Jacques Brel

Enregistrement Public à l’Olympia 1961 & 1964

[Philips; 1962, 1964]

Some of Cheers’ best cold opens serve up enlightened social commentary and an astute punch line faster than Norm Peterson can finish his first beer. “2 Good 2 Be 4 Real” (S4:E7) illustrates the disconnect between three distinct classes of music fans. First, there’s the erudite Diane Chambers, who possesses a great love for the theatre and art that is otherwise foreign to most Americans, which in this case is the French-speaking Jacques Brel. Second, the proletariat Sam Malone dot-connects Diane’s ‘50s and ‘60s Belgian balladeer to American doo-wop and Spector-pop of the era. Finally, there’s the puppy-faced dimwit Woody Boyd, who considers Devo to be an “old group,” and this aired in 1985, mind you.

Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris, the American musical revue that Diane possessed a spare ticket to, did boost Brel’s profile in English-speaking countries, but it isn’t the broadest access point for recent generations. The language barrier might be too much to muster for many English speakers, but this isn’t all pissing in the dark, seeking an open space to safely land. In my case, Scott Walker’s numerous translated cover songs functioned as my gateway into the dark recesses of Brel’s brazen theatricality and risqué subject matter. “Ne Me Quitte Pas,” which is arguably the Belgian chansonnier’s greatest song, practically became monthly required viewing for me on YouTube; that man drips raw emotion! You might also be familiar with Nina Simone’s cover of the song.

Whether or not Brel is the “French older brother” to the likes of Dylan and Cohen, he has influenced everyone from David Bowie to Beirut. The natural extension to my love of his live performances led me to his albums recorded at the Olympia in Paris, where his tongue-twisting vocal acrobatics are in full-effect, whipping and lashing their way through the backside of a Romance language, most notably on “La Valse à Mille Temps.” Brel’s studio recordings sounded flat in comparison to his live performances until the 2003 remasters breathed life into a limp body of work. And if the Olympia recordings don’t satiate your hunger for chanson, Brel’s Infiniment compilation and Édith Piaf might do the trick.

– Michael Tkach

Jens Lekman

Kalendervägen 113.D

[Secretly Canadian; 2007]

Kalendervägen 113.D isn’t a live album in a traditional sense; the only audience for Lekman, his guitar, and his looping pedal are the “old brick walls” of his old apartment as he performs before he moves out. It’s more of an EP, really. Still, it’s a rare treat for Lekman fans, and is a step away from his wonderfully orchestrated material on Night Falls Over Kortedala. Even though his lyrics often penetrate whatever musical surroundings he gives them, Lekman’s lyrics are only helped by empty space. “A Postcard To Nina” gets some proper context, but is still as charming as ever (if not moreso), while “Shirin” is given no introduction – and rightfully so since the song contains all the details the listeners needs. “Friday Night at the Drive-In Bingo” shows that even without the sax, the accordion, and the piano (and everything else), the track still has an infectious energy to it while the a-cappella backdrop on “I’m Leaving You (Because I Don’t Love You)” make the track sound sorrowful, like Lekman is living his regret there and then. It’s a shame we don’t get more of this kind of content from him, but all the more excuse to soak up the goodness from this half-hour gem.

– Ray Finlayson

Jerry Lee Lewis

Live at the Star Club, Hamburg

[Philips; 1964]

Despite all the turmoil and narcissism that could have stifled his artistic vision and set fire to his piano, Jerry Lee Lewis was true to being the Killer onstage; his youthful performances were raw and unhinged, an exercise in rattling the cages of the world’s fiercest predators – which could only be humankind, but I digress – and Live at the Star Club, Hamburg is a monolithic achievement in rock ‘n’ roll history. This 1964 performance captures a grand respite from a number of serious setbacks: in ‘58, a scandalous marriage to his 13-year-old cousin left him effectually blacklisted in the U.S.; ’62 meant the unfortunate drowning death of his son; his contract with Sun Records ended in ’63, leaving his career at a stalemate until he converted to country ballads in the late ‘60s; and the British Invasion threatened to make Lewis’ brand of rock ‘n’ roll obsolete.

The crowd chants of “Jerry! Jerry!” may sound anachronistic to those of us more familiar with the freak show stylings of The Jerry Springer Show than the piano-pounding fervor of a Jerry Lee Lewis show, but the thirteen-song set on Live at the Star Club is one for the music record books. Lewis careens ahead of his backing band, the Nashville Teens, setting the tempo far beyond what seems humanly possible. To the band’s credit, they rarely stumble behind to chew on his dust, keeping pace to the best of their abilities. “Mean Woman Blues” sets his self-referential firestorm in motion, and he only eases up once to play Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart.” The rest of the performance is a rip and a riot, as Lewis demonstrates a stranglehold over both his original hits like “Great Balls of Fire” and covers like Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say.” Put this on and listen to Lewis boogie all over the damn place for 40 minutes, a feat more physically exhausting than modern performances double or triple its length. After this, the heart of rock ‘n’ roll needed a transplant before it could continue beating and return to Beatlemania.

– Michael Tkach

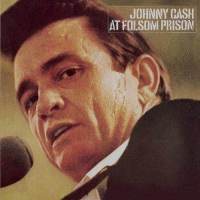

Johnny Cash

At Folsom Prison

[Columbia; 1968]

Any great live album feels like an event unfolding, but At Folsom Prison is something more. It’s a collision of reality with fantasy in an environment of tension and release, set to the tune of rollicking rockabilly.

Johnny Cash spent his career, and lives on now, as the ultimate symbol of a romantic outlaw – a black-coated rebel with a voice like gravel, singing about long nights in the jailhouse and dark deeds. Yet he never spent more than a few hours behind bars. Performing in Folsom Prison, the place that inspired his first hit, Cash’s outlaw fantasy hits the reality of the Big House.

But shanks aren’t thrown at this outsider. Instead Cash, who was inspired to perform at Folsom after its inmates wrote him fan letters, is greeted by shouts and cheers, often highlighting the darkest moments of his songs in a sometimes eerie echo. It’s strange to hear the real life hard-knocks exulting where the spasms of the fantasy reach their peak. Does this mean that Johnny, despite his relative innocence, has tapped into a true outlaw spirit? Or are the men in stripes so taken with the fantasy that they’re willing to compromise?

Like visions of the Old West, reality and legend have blended so closely together in At Folsom Prison that they may not be extricable. Yet when the concert comes to a close, the world checks back in for a very unglamorous ending. As the warden directs the prisoners, the limitations of the pen emerge–no more romance about being a beautiful rebel, but rather the shuffling feet of fellows forced to walk in line.

– Kerri O’Malley