There is no question that time has changed Radiohead. How couldn’t it have? In the last 17 years, the once so productive group released merely two records: the messy, uneven cycle of The King of Limbs – marked by mistrust in the album format and outtakes that vastly exceeded the anticlimactic LP selection – and the elegiac, lamenting A Moon Shaped Pool. In between those, the individual members produced film soundtracks, solo albums, remixes and a variety of other extra-curricular activities. In the meantime, Thom Yorke transformed himself into a sort-of hippie dandy that paraded high fashion on the red carpets of European film festivals, while Jonny Greenwood racked up a problematic Twitter history on multiple topics that contrast the group’s decidedly progressive messaging over the years.

But within all this dialectic, righteous and performed outrage online, the very idea of what Radiohead even represent has been lost. As I wrote in my piece on their Kid A and Amnesiac reissue, the band’s reputation has long been adapted to meme culture, with their thoughtful dissections of corporate indoctrination, capitalist cannibalism and governmental oppression reframed as urban malaise tourism. Maybe this is due to Gen Z’s dismissal of anything overtly melancholic – or just the consequence of 17 years with merely one truly noteworthy group-album in the rear view mirror (and a very sad one at that). Yet irony has it that Radiohead’s aesthetic spirit – that of a unit which explored the cross sections of jazz-infused Krautrock and progressive Britpop – has been transported to a side-project. Which of course heralds the question: are Radiohead dead?

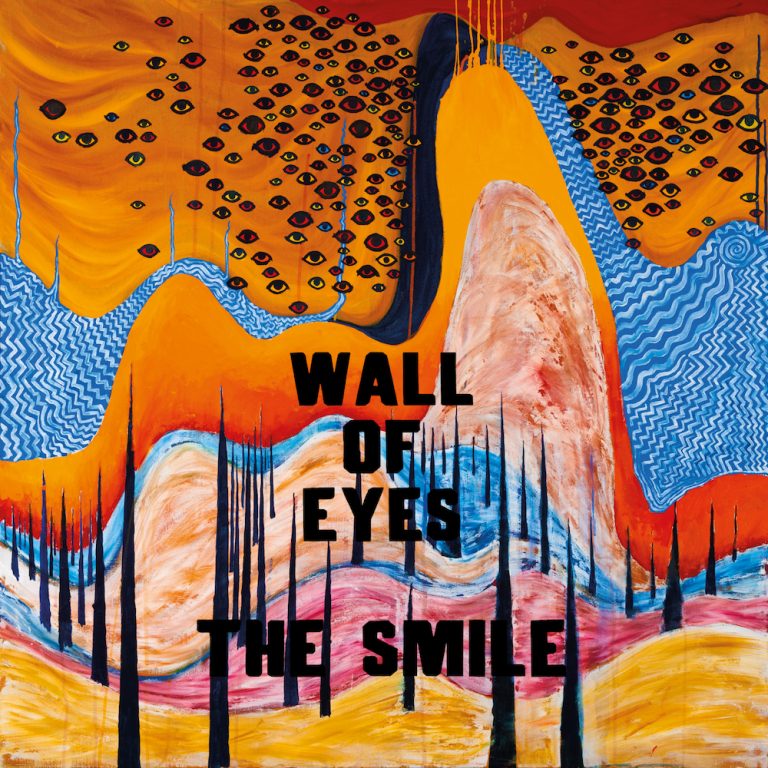

It’s not on me to speculate on that (I’m certain that, at the very least, a reunion show would pay for Yorke’s designer fashion bills), or harp on whether or not the political leanings of its individual members are unacceptable (it’s Twitter, after all) – instead, here I sit, with Wall of Eyes on full display! Over 45 minutes and eight songs, Yorke, Greenwood – often labeled the intellectual core of Radiohead’s songwriting experiments – and Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner expand their venture into progressive pop, started on their debut album as The Smile, A Light for Attracting Attention. It is heady, transcendental music the trio provides listeners with, dipping in and out of modest orchestral beauty, dislocated analogue beats and occasionally sharp guitar textures. It is also wholly expected and on brand. Had the band decided, as a jokey folly, to release Wall of Eyes with a big ‘BY RADIOHEAD’ sticker on its front, nobody would suspect a ruse!

This is both a compliment but also a detrimental issue: how to assess the group’s core duo’s work when Radiohead haven’t been active in almost a decade and discerning features are minimal? And, really, does it even matter when the music is this good? The eight minute journey of “Bending Hectic” could well have originated on A Moon Shaped Pool, as its atmospheric and jazzy guitars lead listeners forward into an achingly sad string section and Skinner’s drums continue to explore the whole reach of expressive spectrum the instrument has to offer. Exploding into noise in its final moments, the song has Yorke revisit his recurring theme of car accidents – this time in the cursed Italian countryside – to muse on self destructive dynamics and inner turmoil. It plays with the dynamics of “A Day in the Life” and is, in itself, a behemoth like few bands can achieve it. The uneasy, paranoid “Read the Room”, meanwhile, uses twin guitars and rhythmic changes to create a sense of constant discomfort, pirouetting around cryptic lyrics centred on greed and power hunger.

The album’s mid-section is where the more progressive leanings of the trio come to fully shine. The spidering “Under Our Pillows”, the analogue-stutter “I Quit” and jazz-prog-pop hit “Friend of a Friend” all stand out in their own ways, playing with climaxes, textures and explorative solos. Somewhere between The Beatles and Gong, “Friend of a Friend” uses string and horn sections to expand on Yorke’s satirical reflections of his urban-dandy persona with images familiar from the lockdown-era: “I can go anywhere that I want / I just gotta turn myself inside out and back to front / With cut out shapes and worn out spaces / Add some sparkles to create the right effect / They’re all smiling, so I guess I’ll stay”. It ends with the singer tumbling out the window of his residence, his riches consumed by starfuckers and fake friends: “All of that money / Where did it go? / In somebody’s pocket / A friend of a friend / All the loose change”.

“Under Our Pillows” is a constant buildup, finally dissolving all melody into a slowly increasing drone, which ends up taking up the entire space of the recording, powerful and brutalist. In stark contrast, “I Quit” is filled with skipping guitars and nervous muted drumming, as Yorke observes the end of a personal journey. The album’s most ‘electronic’ song, it’s both relaxing and kinetic.

Sadly, these stronger tracks highlight more generic compositions, which are all too familiar. “You Know Me” is a ballad of pretty glitches and cerebral piano, but won’t reach Yorke’s best moments in the field, focusing too much on his falsetto and not supporting the lead melody enough. Likewise, the opening title track seems all too comfortable exploring a Can-like vibe, barely challenging its players. Bookending Wall of Eyes, these two give the album a feeling of incidental dynamic – what Yorke has been so great at, creating a sonic narrative that has a clear beginning and end, seems absent, marking the rest of the record as just’s a few great tracks that stand loosely connected.

There is also “Teleharmonic”, a nice but ultimately somewhat skeletal attempt at the urban Electro-Folk melancholia that broke Bon Iver’s weak post-self-titled output – it’s as if, for a moment, The Smile attempt to play by the rules of acts who have attempted to impersonate Yorke (or Greenwood) unsuccessfully. Producer Sam Petts-Davies (who also worked with Yorke on the Suspiria soundtrack) brings fresh ideas of spatial exploration to Yorke’s voice, but perhaps should have pushed an approach that forced these tracks to seek a more elaborate identity or defining edges.

It would have been interesting to see how other Radiohead members could have contributed to the weaker moments here, but then the album also highlights Skinner’s absolutely fantastic drumming sensibilities, which often stand out in their muted, charismatic and unique workings – he easily commands the already great compositions with an even and expressive style and deserves to be praised. Likewise, a Gondry production could have forced a more polished sequence of tracks, but then Petts-Davies is likely involved with the more challenging and original structures present and delivers a sprawling production job.

Not as cohesive, sonically unbound and narratively strong as A Light for Attracting Attention, Wall of Eyes expands the trio’s cinematic nature. This means many of the songs benefit from their own mini-narratives built around strong dynamic ideas, but comes at the cost of poetic progression, making for a more scattershot sequential experience. In this, it sits comfortably in the middle of the vast catalogue of albums released by Radiohead and its members. It’s reassuring to hear that, 35 years after the start of their artistic journey, these musicians can still come up with compositions this elegant and exciting.