So, what became of the likely lads? That’s a good question. We all thought we’d got it made, that the dream would never end. Clubs packed, the beer cheap. We looked good with our long hair falling in front of our eyes, in skinny jeans and uniform. A bunch suburban kids reimagining 1978.

It went too smooth to last – the bands, the sex, the drugs, everything at some point started to suck the life out of you, either ’cause it went to shit or due to our teenage wildlife. But for a brief moment, it felt like the world had changed, and we ran it. I guess that’s what each generation thinks. In hindsight, it’s all too easy to see the cracks in things, the rip in the walls through which the flies came in.

Pete Doherty and Carl Barât at one point were heralded as prophets of a new age – two marauders who projected the sole cool Britannia counterpart to the tsunami of The Strokes, The White Stripes, the other bands who did or didn’t start with ‘The’ that tore down the last remnants of ‘alternative rock’ as it slowly died. Where those American bands looked at CBGB and the late 60s for influence, The Libertines constructed their own origin myth.

The story goes something like this: Doherty and Barât were two former callboys, with an insane amount of homoerotic chemistry and jealousy among them, who invented songs about their projected romantic empire Albion, infected with the genius of Keats and Yates and Wilde, and like no one else – or so would the MySpace shippers try to convince you, as they spun their ‘did they or will they?’ fanfiction of the two. God knows what’s real and what’s manufactured – both Carl and Pete are clever enough to convince not just their fans, but each other of their mythos. By the time things really kicked off, when the band met with Bernard Butler to have him record their songs, it was already over: Doherty showed up to the studio with plastic bags of booze. It started a whirlwind that couldn’t be stopped…

Butler broke down and Mick Jones took over. He produced the group, which previously projected a cross of The Smiths with The Kinks, to make them sound like The Clash during Combat Rock. The Libertines’ debut album Up the Bracket was a rousing, fiery album that frequently stumbled over itself. Doherty couldn’t play guitar, but he was able to infuse every line he drunkenly blurted out with the urgency of someone sentenced to die. Barât countered with his natural vanity, a blasé bohemian who dreamed of aristocracy – two natural contrasts, in turn complementing and antagonising each other.

Eventually, the tension became too much, as concert after concert was cancelled minutes before stage time. Pete succumbed to the beckoning of crack and heroin and was kicked out of the band, burgled Carl’s home, was arrested briefly. The ensuing press circus elevated the group from a cult phenomenon that barely factored into year end lists into the hyper-fixation of a generation. Indie sleaze before there were hashtags! Things smoothed over briefly, long enough for a second, self-titled record to manifest, which was even more forlorn, ramshackle and amateurish – its success has become more a document of contemporary narrative than inherent quality. By the time it was out, so was Doherty from the band, again, this time for good, as hundreds of ‘kids’ impersonated the duo’s cover-posture for their MySpaces, hand-drawn tattoos and all.

What came after is now hazy. Pete conceived Babyshambles, and took Mick Jones with him to record an auto-parody insult of an album, which of course sold fantastically, while Carl cleaned up his sound and started the Indie-supergroup Dirty Pretty Things, who were blatantly better. But by then, indie had become nothing more than a marketing term.

Doherty got better with each recording for a while, until the well ran dry, his magnetic energy only communicating during the occasional late-night performance, if he dared to show up. Barât settled in France and continued his role of l’age d’or gigolo. Why they finally got back together is anyone’s guess – maybe the bank account dried up, or maybe the two got nostalgic. Maybe Doherty cleaned up, or maybe they really do love each other as much as the slashfic writers imagined back when. There was a reunion record in 2015 and proper tours. Middle age had approached and taken any sense of wonder in… but things seemed stable enough. Families, sobriety, their own hotel and gin on top of it. You can’t let stories like this end like that.

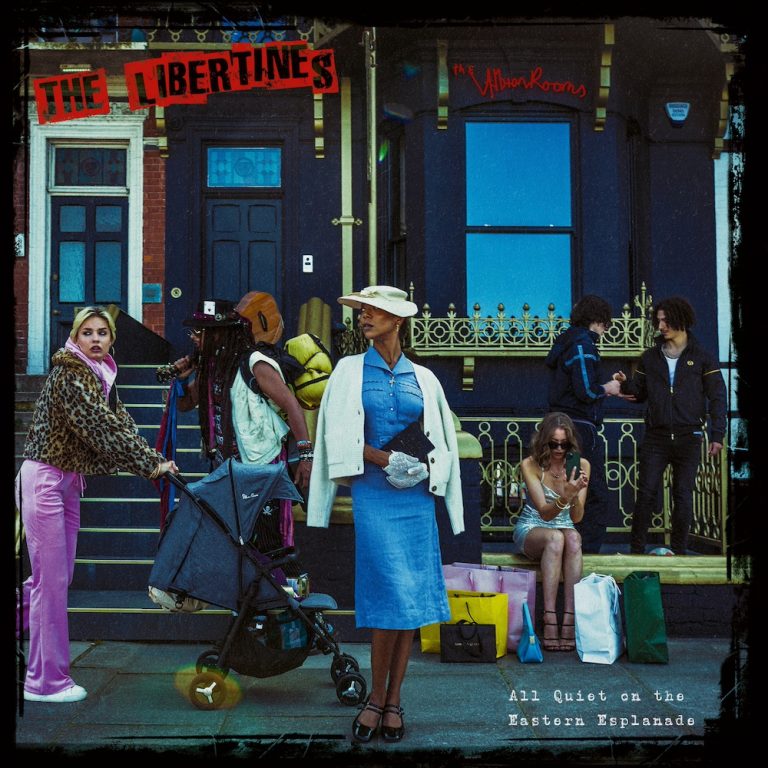

All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade comes 20 years after the band’s era defining self-titled second album – and with none of its hype. The record exists to fulfil contractual ideas of what The Libertines are, or could be, now: well kempt, branded, displayed, ready for consumption. The cover is a stilted photoshoot of clichés, contrasting the flash-drowned intimacy of the artwork that preceded it by two decades. The music is recorded in studio cabins, reduced to the best takes, one player at a time. The lyrics are political – excuse me, “political”; they comment on what’s happened in the nine years since the last release, Brexit and refugees and all that.

“Merry Old England” is about the latter, with Doherty complaining about the UK’s “chalk cliffs, once white, they’re greying in the sodium light, oh / My, my, my, my congrats on staying alive / Hope they don’t catch you tonight”. They’re moderately amusing reflections, with very little wit and a lot of heart. “I Have a Friend” is about the war in Ukraine, and reportedly followed Doherty’s proclamation “NATO are going to step in any day, are we too old to enlist?” The lyrics are hardly as angry, and seem the product of a man who’s analyzing today’s youth through the pen of conservative thinktanks: “No, you don’t know you’re born, free speech and free porn / And the next thing you know you’re being led out at dawn […] And now your shadow’s a skull, and the skull is a hole / The hole is empty of course like all human discourse“.

References do abound, but now they seem more like window dressing than an attempt to reconnect with the romantic iconoclasts. “Night of the Hunter” might be the worst offender of this. Instead of investigating the true sources of juvenile knife-violence in the UK, Doherty just tiresomely describes Robert Mitchum’s villain role with no further arabesques or metaphors: “Love and hate / Tattooed on the knuckles ’round the handles of a blade / On the knuckles ’round the handles of a blade / A bloody blade”. Musically, the track attempts Ennio Morricone, but sounds more like the soundtrack to a crisps commercial, all faux Western postures and hollow irony.

By now, halfway through the record, it becomes clear that much of the duo’s lyricism is reduced to regurgitations and repetitions of previous verses. The British language has always been an imperial one, constructed to hide intentions through emotional and symbolic status signifiers: vulgarities must be evaded at any cost, cutifications are an integral part of social masquerade. The way a person speaks immediately reveals their class status, but Doherty just recounts banal verbiage: “I was calling to tell you, baby / They’re taking me away for a while / Ah, you can’t blame me, it’s this world that’s made me”. It’s bad enough that Doherty can’t write like Doherty anymore – what’s worse is that he doesn’t sound like himself, either. For the first few songs, his McCartney-like organ seems wholly absent, until the ears finally manage to catch some hints of them. Yes, his voice is now completely different, at times coming so close to Barât’s that it is hard to tell the two apart.

Barât, on his end, continues in the role he was born to play, romanticizing the fairly boring rock’n’roll postures that he embodies. “Oh Shit” and “Run Run Run” are portraits of reckless hedonism and brave escapism, sung and played by dads. They’re fine indie rock songs, even featuring the stream of consciousness singing style The Libertines perfected on their first two albums. “Be Young” reflects similar images in the shadow of climate change – rocking with a conscience and a quick reggae interlude, naughty naughty you filthy ol’ soomka!

There’s some fun in Barât’s songs though, as they reconnect with a sort of classic British collage songwriting style that is inherently ironic in its choices of genre-mash-up. They also feel much more alive than the mostly string accompanied ballads Doherty came up with. Granted, he finally dug out the corpse of “Songs They Never Play On The Radio”, a demo that has haunted his bootleg releases for many years. This is likely the best the song could ever become, a cute mid-tempo throwback to “Let It Be”, before it slowly graduates into referential classical. Sadly it’s still infused with the same old tendency for clichés that the record suffers from: “I’m crashing down the boulevard of broken dreams / Men my class we live too fast and we can’t be arsed”. Written at the beginning stages of Doherty’s self-immolation, it now seems like a self fulfilling prophecy: Carl’s new verse accurately describes the status the group has with the generation they once impersonated (“Since 45s they’re digitized it’s heart bereft and his left is deft / Songs that they never play on your radio / You can stream it now for free and save your soul”).

All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade at times feels like a strange attempt to lionize the cultural heritage of the very place it meant to critique. It’s possible that Doherty’s military upbringing is to blame for instilling an undying respect for the disintegrating empire in him, as his takedowns still conjure mythical landscapes of the past.

Barât, meanwhile, attempts to include some odd musical references as metatext – such as on the Margate-hymn “Mustang”, which borrow’s the refrain of Psychic TV’s “Godstar”, the melody of The Velvet Underground’s “Sweet Jane” and the chants of “All You Need Is Love” for good measure. Supposedly an epic with 10 verses, it was cut down and now retains little of what could have made it a significant standout both on the album and in the current climate of risk-averse, stream friendly editing.

Speaking of listener friendliness, another casualty of the Libertines’ trademark-sound that most might not notice, but which impacts the album considerably, is a switch in Gary Powell’s drumming. The most approachable (and coolest) Libertine always stood out with a somewhat manic, unbound style, which gave the group a sense of constant tumbling motions. He’s much less unique in his playing here, which might be less his fault than just choice of overall direction. There’s not much here to tumble towards, or run away from.

At times, All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade feels like an alternate universe Suede record, one where Brett Anderson had attempted a comeback all on his own, focusing on comfort and intent to fulfil whatever bargain he was given to please ageing fans. Listening to the new Libertines record, I can’t help but remember his assessment that during each live show, he completely exhausts himself in front of an audience, until suddenly during one song – old or new – a breaking point is reached, upon which he completely lets loose and shares a euphoric state with the audience which, to the end, won’t stop. Anyone who’s seen that can attest to this ageing madman’s spirit being absolutely awesome, and this philosophy aligns itself with the ambition to deliver a unique, iconoclastic new record on each new turn. It defies the idea of a “comeback”, or of nostalgia, and leads to immense surprises and an animated catalogue.

The Libertines, with their second comeback, have chosen the other, “safe” direction, and sacrificed their integrity for it. Doherty sounds tired, abandoning nostalgia for kitschy gestures. Barât has fun, putting on his old jacket and playing rockstar, but he’s not rethinking his role as musician, or portraying growth as a songwriter.

What became of the likely lads? Most studied business. The clever ones had kids and found salvation in family. Someone died recently, I heard, just a few years older than me – bad food, bad drugs, a life trying to prove something. Those who went to art-school soon entered a cycle of bourgeois rituals, ending up in interior design-art that regurgitates the same themes. The Libertines moved to France, had kids, opened a hotel in Margate, sold their own gin, made a record you can have a hot cocoa to, lying down in your comfy chair.

Oh, and me?

I’m right here.

I listened to it on my own.

Hey,

does anybody want to start a fire?