It’s no surprise or spoiler, but Spencer Krug‘s Twenty Twenty Twenty Twenty One is a diaristic album. The new record from the Canadian indie icon gathers together songs written and recorded over the titular years, all of which were released on his Patreon page. In a similar way to his 2021 album Fading Graffiti, Krug compiled a bunch of his favourites into a neat package to release out onto the world (once again on his own record label, Pronounced Kroog).

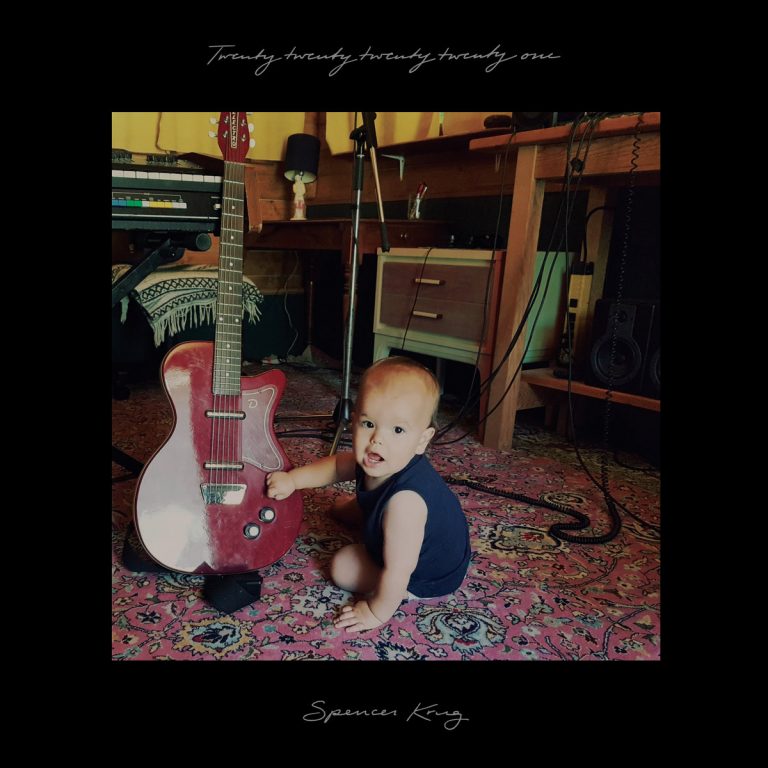

That’s about where the similarities between both releases end though. While Fading Graffiti was something of a breath of fresh air – a chance to finally get together with musician friends and make music as a collective – Twenty Twenty embraces the secluded noodling of Krug’s own home studio. Apart from some remixing (done alongside friend Jordan Koop) and the odd additional touch from an external musician here and there, the songs on the album remain largely as they were heard when they were released to fans across 2020 and 2021.

The album, then, is something quite unlike anything from Krug’s wide and varied oeuvre – and this is from a musician who has never been afraid to venture into texturally percussive dreamworlds (see the vast majority of his output as Moonface), rock-opera like-theatricality (Sunset Rubdown’s Random Spirit Lover), or teaming up with a Finnish band unknown to many (his with work with Siinai). At times Twenty Twenty‘s most valid referential comparison is Krug’s work with Dan Bejar and Carey Mercer as part of the indie supergroup Swan Lake.

At its heart though, Twenty Twenty sounds like modern day Spencer Krug. To the casual listener the album may be jarring and indulgently experimental in sound (see the female robotic voice on the beguiling “Bone Grey” or the shimmering steel drum-like reverberation on “My Puppeteer”), but to those who have been following Krug’s output, the album sounds exactly where Krug has led himself through the years. Going it solo (expect times when he’s not, thanks to Wolf Parade enjoying some modest success and a new life after their 2011 hiatus), he’s been able to make the music he wants to make. Sometimes that’s a track of Rhodes riffs spliced together in the back of a van while on tour (“Chisel Chisel Stone Stone”) and sometimes it’s a seven-minute strangely effervescent and pagan-like track that sounds like the musings of a man pacing the floors impatiently during lockdown (“Cut the Eyeholes Out So I Can See”).

While there might be an adjustment period needed for some, the album’s best moments come in various guises. Self-described “anti-nihilism ballad” and opening track “Slipping In and Out of The Pool” marries an acoustic led track with spacey synths, all with a great lyrical hook that reads like a middle-finger barb to pessimists (“I think an hourglass is different than quicksand”). And speaking of guitars, it’s genuinely great to Krug belt out an acoustic ballad with conviction like he does on “My Muscles Are Fine”, a song that (to steal one of the man’s own lines), deals with growing old with grace. “Despite how it looks I am not turning into some ocean monster who forgets his way home / But I won’t regret the good times / My muscles are fine, it’s in my fucking bones,” he chimes with that bit of desperation so as to try stave off having to reckon with reality and time.

Because the majority of these tracks were written during the lockdown months, the pandemic and the way life changed seeps into the lyrics. On the rather beautiful but doomed-sounding “Hanging Off the Edge”, Krug muses over how “First came the death of old ways / Then came the birth of the new.” With blocky piano chords and fluttery right hand melodies, it’s a reminder not just of his exemplary 2013 album Julia With Blue Jeans On, but also how he could silence a room when reverting back to the ways people might expect him to perform.

But, with a wide and varied catalogue, Krug has already proved his talents. We know his strengths and his style, like the way he’ll throw out an unassuming phrase that is both poetically clever and welcoming wise; “There’s gonna be a revolution / Just as soon as we’ve finished our meal,” he posits on “Overcast Afternoon” with a tiny smirk. He’s at a point where (thanks to the likes of his Patreon) he can make the music he wants to make. The music that represents him and his life. As on Fading Graffiti, here he reckons with familial life, less concerned with mythical beasts as he is with mother nature causing leaks in his studio shed.

Twenty Twenty is a snapshot of the two years of work to get to where he is now. It’s not re-invention, but rather evolution. He says it best himself on “How We Have to Live”: “I sometimes wonder if I haven’t in some ways already died / Then I think of course I have and so has any person who just burns to stay alive.” Krug’s flames are still burning, and so long as he continues to be able to explore the avenues he wants at his own pace, the fire is safe from being extinguished and will only grow in new and curious ways.