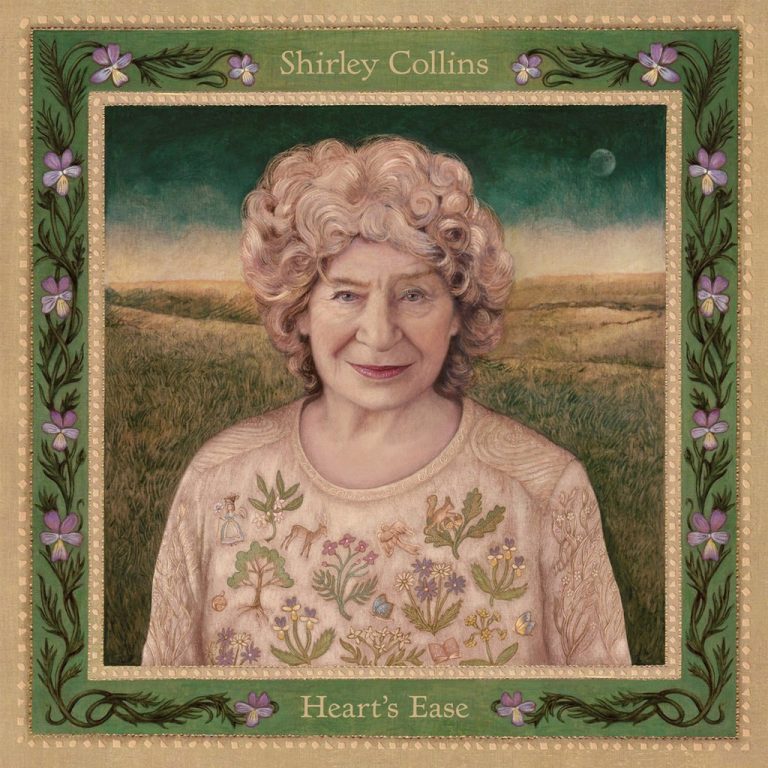

Shirley Collins is 85 years old. The fact that she is still recording is remarkable enough on its own, and even more so when taking into account that she took a nearly 40-year hiatus from recording entirely. A beloved singer who played a significant role in the 1960s English folk revival, Collins entered a period of depression in the late 70s and subsequently lost her voice, effectively ending her career—or so she thought. Encouraged by a younger generation of musicians who admired her work, Collins released a new album, Lodestar, in 2016, and four years later she’s returned with Heart’s Ease, an album that is just as much of a pleasant surprise as its predecessor.

To say that nothing has changed since her heyday would be inaccurate; Collins’ light, youthful soprano has aged into a weathered contralto. You can feel the many years behind her voice, just as you can feel the history behind her words. But the intention behind her music has not changed: Collins utilizes her humble, unadorned singing style as a vehicle for storytelling and prolonging the folk tradition. Collins has described folk as “the archaeology of music,” and as something that she’s absolutely consumed by: “I have always loved it so much. I’m still learning songs and just want to keep learning them. I thought ‘somebody has got to sing these songs, so it might as well be me!’”

Collins’ fascination with folk music took her on a 1959 trip with ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax throughout the American South to collect and record folksongs from a variety of traditions. One of these recordings included Ozark singer Almeda Smith’s rendition of “Merry Golden Tree”, an Anglo-American ballad recounting a tale of treachery at sea. This sinister story of two ships in “the lonesome lowland sea” is how Collins chooses to open Heart’s Ease, and it’s a fitting introduction. Collins has always been drawn to the darker side of folk—murder ballads, cautionary tales, and betrayals feature prominently in her catalogue. Collins’ version of “Merry Golden Tree” is cheerful and bright, making the story of “drowning in the lonely lowland sea” all the more jarring. This juxtaposition of tales of darkness with singsong melodies and charming arrangements has a long history in English folk music; Collins uses it to full effect here.

Another track with origins in the 1959 trip is “Wondrous Love”, a shape-note hymn that Collins first encountered in Alabama. Shape-note singing, also known as Sacred Harp, is an American tradition of a cappella singing with a unique notation system designed to be accessible to anyone regardless of musical background, and a distinctively resonant style of harmony. Collins gives the tune a decidedly more English rendition, accompanied by mandolin and percussive guitar playing. But the yearning devotion of the Sacred Harp tradition is expressed in her resolute vocals: “And when from death I’m free, I’ll sing on / Through all eternity, I’ll sing on.” No words on the album feel more pertinent than these.

There are also plenty of traditional English songs (and even one dance). Of particular interest is “Barbara Allen”, a centuries-old ballad that Collins first learned in school. This is not Collins’ first recording of the song, which tells the story of “hard-hearted Barbara Allen,” who has a change of heart after an ailing suitor she rejected dies. In 1959, Collins recorded a rendition set to a tune she had composed herself, feeling that the plain melody she had learned in school did not suffice. The 1959 version of the song is morose and haunting, laying bare the story’s tragic and cautionary nature. But almost sixty years later, Collins decided to record a version of the song set to its original melody; the simple refrain that gives the song a bittersweet touch, adding an angle that is completely missing from the 1959 recording.

Heart’s Ease also features a small handful of non-traditional songs, all of which have a sense of heritage of their own. The lyrics of the lovely “Sweet Greens and Blues” were penned in 1965 by Collins’ then-husband, and present a snapshot of their life at the time with their young children, not without a subtle awareness of the ephemerality of the moment. The evocative “Locked in Ice”, written by Collins’ nephew, tells the true story of a lost “little ghost ship on the Beaufort Sea, doomed to travel endlessly.” Striking closer “Crowlink” is almost entirely instrumental, featuring an enchanting combination of hurdy gurdy and field recordings; for a fleeting moment you can hear Collins’ voice through the mist, but it vanishes so quickly that you begin to wonder if it was really there.

Heart’s Ease captures the Shirley Collins of the present day, and is in no way an attempt to recreate times passed. And yet the continuity is crystal clear: Collins’ devotion to the folk tradition is as strong as ever. She continues to bring new life to the musical artefact that is the folk song, and the fact that she brings so many years of her own to these interpretations makes them feel all the more authentic.