I don’t think there is any pop-star after the mid-90s who’s had as much a grip over the international charts as Robbie Williams did during his heyday. In the six year period from 1997’s Life Thru A Lens all the way to the release of 2002’s Escapology, Williams managed a significant number of top hits and blockbuster albums, crossing over any preconceived notions of focus groups and audience bubbles. Yes, there’s other large pop stars, obviously – but they either burned out quickly, pivoted away from the singles market or followed a cataclysmic up-and-down trajectory. Williams changed the game multiple times – he somehow made lounge-pop cool, did Brit-pop as the genre was transforming into avant-garde experimentation and somehow not only gave swing a sudden resurgence, but also saw every other pop-act try to replicate his novelty album Swing When You’re Winning. It’s easy to see why Williams was so successful: he combined the sardonic irony of Morrissey with the on-stage machismo of Mick Jagger – contradictions that crafted a self-deprecating, boyish mate. A guy who could play the pint-pounding bare-knuckle fighter, but would apologetically bemoan his micro-penis in the “Rock DJ” music video.

But behind all the irony was something more fragile. Williams was one of the most open pop stars our generation might have seen, openly laying out his self-hatred and insecurities. Often flirting with homosexual entendre, Williams portrayed himself as the self-doubting crypto-bisexual who, in his own words, was 49% gay. But then, also, wasn’t, but wanted to be. It might sound mighty confusing to people in the current age of sexual liberation, but it makes sense when you see Williams as somebody who has fought with industry regulation, going as far as the terminating pregnancy of his former girlfriend, All Saints’ Nicole Appleton, his sinister experiences with drugs and constant press inquiries.

After his exit from Take That, Williams was marketed as a once-in-a-lifetime pop star, a male Madonna. But in reality, he alternatingly wanted to be Neil Hannon of The Divine Comedy – a suave, cultivated crooner – and a third Gallagher, delivering uplifting Beatle-esque anthems. His closest confidant, songwriter Guy Chambers, delivered this cross with him, crafting tracks that nodded or lifted from “I Will Survive”, “You Only Live Twice”, “Relax”. It worked, until it didn’t: at Williams’ peak, the Jonas Åkerlund directed video of “Come Undone” proved to be both climactic and prophetic.

Much has been made of what followed. A split with Chambers led Williams to join with former Duran Duran member Stephen Duffy. The resulting album Intensive Care was politely written off. The club-centric follow-up Rudebox hit just one year later and failed spectacularly. It’s one of the oddest cocaine-vibe albums ever to be released, which makes it at least fascinating, but it’s easily explained as attempting to connect with the Gorillaz sound that Damon Albarn nailed.

Since then, Williams has swung in-and-out of artistic lucidity. Fatherhood, new album, drugs, comeback attempt, obscurity, reconnection with Chambers, back and forth. Neither Reality Killed the Video Star nor Take The Crown reconnected with his former success. A second swing album came and went.

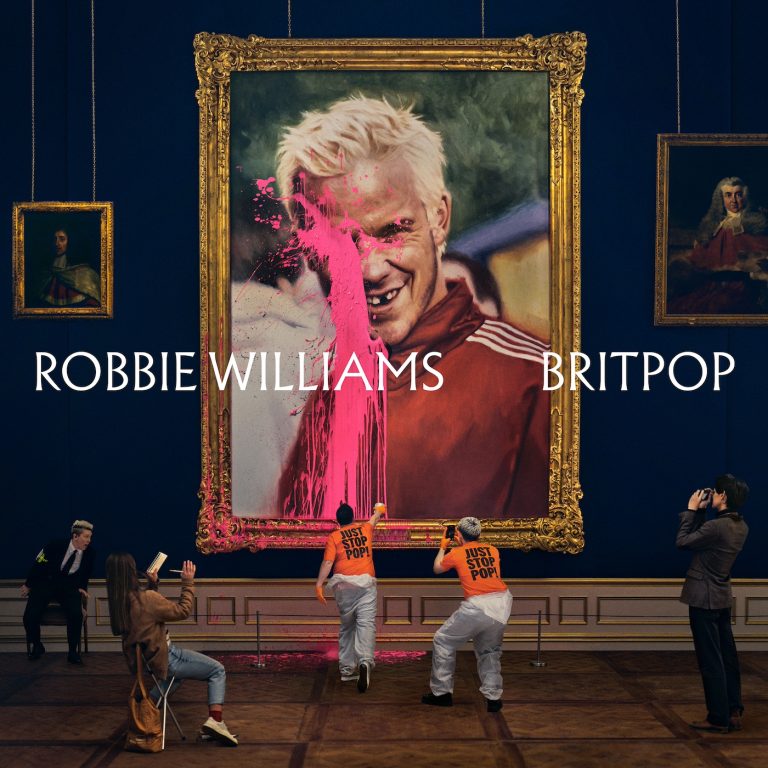

In the 10 years between now and his prior studio album, The Heavy Entertainment Show, he only released a Christmas-album and a re-recording project, XXV. But there was one notable moment for Williams: the release of the monkey-led biopic Better Man, an unvarnished and brutal portrait of the artist’s life, cleverly employing a chaotic CGI chimp where an actor could have felt generic: Williams is larger than life. During the making of the film, Williams swung in and out of studios all across the globe, experimented with different writers and producers. The result is Britpop.

Of course it’s called Britpop, come on now! As stated above, Williams always wanted to be part of that clique, and it’s been speculated that Hannon wasn’t only a fixture for Williams, but that he potentially ghost-wrote for him. To be fair, Williams could front Oasis, but Liam Gallagher could never be Robbie Williams.

But surprisingly, Britpop isn’t very Britpop: it’s the heaviest, loudest, least subtle Williams outing. That is immediately evident with the Tony Iommi guesting opening rocker “Rocket”, which doesn’t even make it to three minutes and burns the barn. “Spies” goes for arena rock, a less sinister “Come Undone” that wants to swing for the fences. “Pretty Face” has a hint of Elastica to it, but ends up more mid-period Oasis, while “Bite Your Tongue” features more than a hint of Blur’s The Great Escape whimsy and “Cocky” has a bit of Liam’s swagger ca. “Lyla”.

The album is already at the halfway point and one thing becomes apparent: the tracks are all quite mono-syllabic rockers, most barely make it to last three minutes. They feature the whimsical post-60s frivolities britpop is so well known for and come with a certain punk edge. But they also lack the tragic tone that made so many Williams songs into immediate classics. The loud guitars and pounding drums celebrate a return, but erase all sensitivity. There’s also few memorable hooks here, and not many bridges that lift a potentially generic verse through clever contrast. It’s all a little Kasabian.

The heavy ballad “All My Life” is the most apparent Oasis nod, with the somewhat Lennon-esque refrain and Williams’ vocals very close to Liam’s vocal tone, including “My oh maaaaa-iiiiiih”. After this, Williams takes the foot off the gas pedal: “Human” is a pretty synth-led ballad with a great vocal melody, a (very faint) hint of Kraftwerk and a memorable singalong refrain. It’s the first real standout track of the album and could well stand among Williams’ classics.

The somewhat satirical “Morrissey”, not so much. Led by a throbbing post-Moroder electronic beat that could fit both on a Charli XCX or Antonoff-helmed Swift track, it’s a bit too evident in attempting to connect with the zeitgeist. What’s funny is that Williams uses Morrissey’s failings – his constant self-victimisation and petty grumpiness – to reflect on his own struggles with self-loathing. The main issue with the lyrics, however, comes with the realisation that Williams paints a very rudimentary image of his subject, writing about the idea of Morrissey more so than the man. Surely that will lead to even more self-pittying of the mancunian, but well…

Following, Williams returns to the Britpop pastiche: “You” is a direct reference to Elastica’s “Connection” – which, famously, they took from Wire. The refrain turns to post-Butler-era Suede, which makes for a continually weird collage. These post-modern songs all came 30 years ago, but to Williams, they must seem very modern. It’s quite speculative and won’t really come together, even if the spirit is appreciated. “It’s OK Until The Drugs Stop Working” leans towards the ironic orchestral pop Pulp perfected and is a really strong track, but at three minutes 16 seconds a little too short where it could have benefitted from a grand finale or spoken word section that just spirals on and on to ecstasy. And then the closer already comes: “Pocket Rocket” is a cute, string led reworking of the opening track – arguably a better fit for the composition. At just 38 minutes, Britpop is over.

It’s understandable that this album took a while. Williams was likely busy overseeing the creation of his biopic, traveled a lot, sought inspiration with different producers and musicians. The songs often seem to provide a fertile ground for Williams to showcase the very persona he possibly wished to have embodied during his heyday: a cool art-school kid that was self-determined and well read, a person celebrated for his human failings by the NME, rather than somebody constantly chastised for his struggles by The Mirror. When rockstars throw a tantrum on stage or fists during recording sessions, it’s fucking cool, after all.

But as spunky and charming as Britpop presents itself, it continues to prove that Williams struggles with an identity crisis. Look: there’s not a single track on here as queer as “Girls & Boys”, which Blur whipped into a lurid five minute dancefloor banger. One of Britpop’s unsung qualities is how cleverly it played with gender – yes, even the hyper-masculine machismo of the Gallaghers is ultimately a performance. Britpop is now often associated with a conservative nostalgia, in contrast to the futuristic sounds of shoegaze, trip hop and the myriad of Warp acts of the 90s. But that totally evades the fact that Britpop was often unflinchingly critical of British society. It was as arty as it had teeth.

Britpop, the album, evades this edge in favour of introspection. Williams reflects on his life and himself, but rarely takes a step away to fully elaborate on the the UK and its politics. “Bite Your Tongue” is a rare moment of political writing, but its musical execution is too unwieldy in its mid 90s tone – an experiment with a style that climaxed 30 years ago. But all this doesn’t mean that Williams first real record in a decade is by any means bad. Because it isn’t.

But then it also isn’t so many other things: it isn’t very memorable, it isn’t very emotionally resonant. It feels like a short, quick project that Williams could have done in 1999, at the tail-end of Britpop, the same year that Blur released their genre-shattering classic 13. It’s clear that Williams had fun here, that he was able to embrace some of his contemporaries and heroes. But it never feels like a classic record, a necessary record, a weighty record.

At his best, Williams opened himself up to a deep sadness that would fracture across even his brightest hits and provide the same euphoric melancholy that the Pet Shop Boys, Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson master so effortlessly: “Road to Mandalay”, “Come Undone”, “No Regrets”, “Angels”, “Strong”. Britpop isn’t touching that perfection, but it provides a strong shield for Williams to rebuild what looked like an ailing career. It’s, possibly, a blueprint from which he can re-assess his identity by looking at the past he wishes he had had. That’s a fairly worthwhile endeavour, even if it can’t touch his classics.