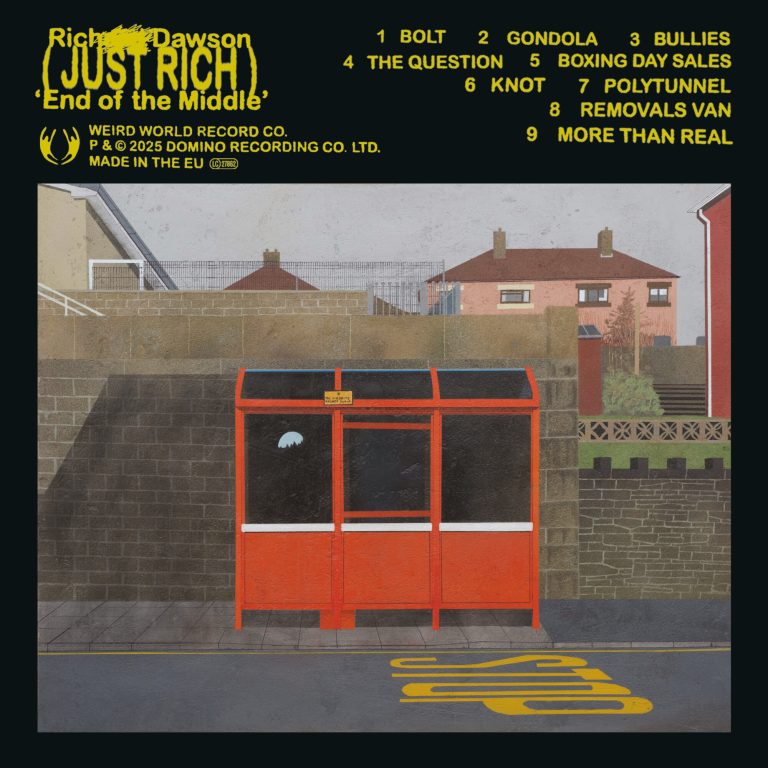

Newcastle songwriter Richard Dawson has been prolific in recent years. His new record End Of The Middle is the fourth to bear his name since 2019, and in the same period he put out a record with his band Hen Ogledd and numerous other odds and ends. Across these releases we’ve heard him dreaming up fantasy tales across 41-minute tracks, jamming alongside Finnish metal band Circle and voyaging to made-up worlds alongside fellow North England musicians. However, no matter the musical approach, his strength has always been the tales he tells.

For End Of The Middle he makes the canny decision to strip things back – both musically and lyrically. Aurally, the album is very much focused on his guitar, with the drums almost whispering in the background in partnership with tastefully placed wind instrumentation, scant piano and a few well-earned moments of brass fanfare for emphasis. His stories here centre around normal people; specifically the family unit and the daily and generational dynamics that play out between its members. He manages to do it with such specific yet universal truth that the result is his most heartfelt and affecting work.

It starts with “Bolt”, which sets up this family picture, Dawson sketching them in their various humdrum activities: “I’m in the hall on the phone / Jen’s in her room watching Neighbours / Dad’s in the bath whistling / Mam’s on the sofa reading yesterday’s paper.” Having said that, what happens next – a lightning bolt strikes the house, nearly frying him down the phone line – stands out from the rest of the record because it is such an unlikely event. With the exception of the ghostly apparition of a former station master in “The question”, everything else on End Of The Middle feels like it could be a retelling of something that has happened to your family or one you know.

As is Dawson’s wont, the truths of these quotidian tales often lean into the melancholic and wistful side of people’s existence. On the nimble shuffle of “Gondola” he sings from the point of view of a grandma who never got to go to Venice, wondering “how many summers have I got left?” She then determines to set aside some money to go on that trip of a lifetime with her granddaughter and “make memories before it’s all too late”. The stunning, slow-blossoming acoustic stroll of “Polytunnel” is even more heartbreaking as it tells the tale of someone who goes frequently to the allotment as its their “happy place” – the two words sung with an aching pathos. Between descriptions of the kinds of activities they get up to at the allotment, Dawson slips in the line “It was Karen who was always the green-fingered one”, leaving the listener to fill in the blanks about the loss the narrator has suffered and the solace they find in their gardening.

Album centrepiece “Knot” is the standout of these songs of personal strife. Over gloomy guitar chords and brushed drums, Dawson takes on the persona of someone suffering deep depression who is trying to put on a brave face as they go to the wedding of an old friend. Their “soul is sick – a herring-gull in an oil slick” and this gloom is impossible to shift; the “strangling shame” persists even as the audience is treated to a bird of prey display, a golden retriever in a waistcoat and dickybow and streams of confetti after the nuptials are pronounced. A beautiful clarinet solo flits through the song as dad dancing takes place; meanwhile Dawson’s character hoovers down finger foods and alcohol before drunkenly partaking in karaoke – “Is it me who butchers ‘My Heart Will Go On’?” Inevitably, there are fights and fallings out, punctuated by a beautifully cataclysmic fuzz guitar and brass finale.

Beyond the individual strife, Dawson takes his songwriting to another level by tying together generations on a number of these tracks. The first is “Bullies”, where he and his bandmates produce a light version of metal riffing to underscore his recollections of school days being laughed at, punched in the face, spat on – and ultimately messing up his GCSEs. Things then jump to this character as a parent, getting a call from school in the middle of the workday to say his son has been in a fight and is being suspended. As he arrives to collect his errant child, his dread at returning through the school gates is palpable, so he clings to the memory of the one teacher he liked, asking if she still works there (“she’s taking some well-deserved leave”). We don’t hear the full fall-out of the son’s bad behaviour, but after a week of “barely talking at all” the narrator turns to him and softly concedes “I know you’ve got a good heart” – an acknowledgement that, while breaking someone’s jaw is unacceptable, the parent knows school life is complicated and difficult for a teen.

In the final two songs of End Of The Middle we get something like the full circle of life. “Removals van” finds a young couple in the midst of moving houses, and the packing up of all of their earthly belongings naturally sends the narrator down memory lane. What starts with great childhood memories (“staying up late to watch the England-Germany semi-final”) soon turns sour as he recalls his father becoming redundant. This leaves him constantly drinking in front of the TV and getting into shouting matches until one day he storms out, never to return. Between these stormy recollections, Dawson relays the hope and hard work that is going into creating the new home his family is moving into, in which the pure hope seeks to blot out the possibility of repeating the mistakes of the father – especially as “it won’t be long ‘til the baby arrives”.

The album closes on “More than real”, a regal synth hymn that finds a family gathering around their father in hospital in his final moments. Anyone who has been in a situation like this will recognise the details, sung by Hen Ogledd bandmate Sally Pilkington: “take a sponge, wet his lips, stroke his cheek and gently comb his hair / I don’t know if he can hear us but I think he can”. Once he has slipped away, the slow and painful healing begins – a process that will be undertaken together, as a family.

By paring back his approach, Dawson has been able to acutely focus on the interpersonal relationships that form the structures of a family. He points out the faultlines that are the source of so many scars that we all recognise, but has also made sure that we see and feel that when these wounds are tended to the bonds between these familial facets grow stronger and deeper. The result is the rawest and truest set of songs in his career to date.