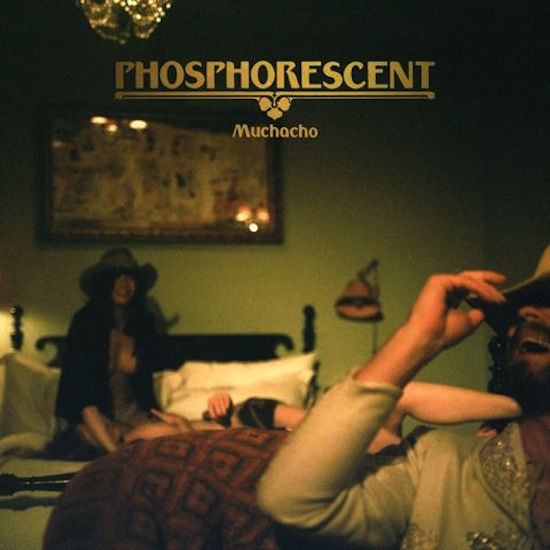

Phosphorescent’s last album was called Here’s To Taking It Easy. It was hard to know whether to take Matthew Houck’s statement at face value or whether there was a certain irony to it. On the one hand you had sentiments like “love me foolishly” and “I don’t care if there’s cursing” suggesting that he was indeed finding it easier to be more care free, and then on the other hand you had the soul crushing heartbreak of songs like “The Mermaid Parade” and the deceptively upbeat tale of a desperate man in “Heaven, Sittin’ Down,” amongst others. Phosphorescent’s new album still veers around the subjects of love and lust in a way that makes it clear that Houck’s still unclear exactly how he feels about it all (though his utmost passion in every song is never in doubt). He’s decided to title it simply Muchacho; almost like a dressing-down of himself, admitting he’s just a man, ruled by his emotions, consequences be damned.

Almost every song on Muchacho concerns Houck’s ill-fated relationships with women, but the way he approaches and feels out the subject can be wildly different from track to track. This is perhaps most obvious in the album’s first two songs (following the koan introduction), “Song For Zula” and “Ride On/Right On.” On the former violin-laden track we have a disconsolate Houck, looking back on a relationship that went south, and realizing now that love is not “a burning thing” but in fact “a fading thing, just as fickle as a feather in a stream”; something that “disfigured” and “caged” him, painting it as an omnipotent emotion. While “Ride On/Right On” follows is an uppity guitar-led track in which Houck casts himself as a lascivious biker travelling from bar to bar, loving the feel of women’s hands on him as he rides his bike (and so much more), where love isn’t even in consideration.

These strange poles of emotion can seem hard to balance, until we get to the album’s centerpiece “Muchacho’s Tune,” the first track written for the album and probably the most honest. Amidst a lilting, watery, downbeat jaunt, Houck is confessional, addressing his reckless side, mentioning his small fame, his drug use and plainly stating “I’ve been fucked up and I’ve been a fool.” This honesty and outpouring of grief brings out his loving side, where he ultimately decides to “fix [him]self up, and come and be with you,” and the defeated way in which Houck delivers this line makes you feel the weight of his tribulations and the seriousness of this resolution.

In interviews Houck has stated that he hopes the production on this album is a step up from his previous efforts, and has specifically mentioned Brian Eno’s 70s output as an influence. This is certainly audible in some of the wider and airier tracks on here; most notably the placid soundscape created by the violins on “Song For Zula” and the horns that subtly add wings to “Down To Go.” What’s more notable is how everything from drum sound to cascading pianos, pedal steel, violins and more are implemented so precisely that they bolster the sounds and the strengths of all the songs. To the point where sometimes you might not even notice how much is going on. This is undoubtedly a feather in the cap for Houck as a producer, but at the same time it can feel like Phosphorescent have lost some of the Americana spirit that went into Here’s To Taking It Easy, where the songs felt looser and more ramshackle, like any of the instruments could fly off the handle in a moment of inspiration. There are a couple of moments like this on Muchacho, such as the grand and boisterous side one closer “A Charm/A Blade” and the rollicking “The Quotidian Beasts,” but moreover it feels like the band is evolving with a more focused and manicured sound. Nevertheless, the passion fueling every song is never in doubt when you have a lyricist and vocalist like Houck at the helm.

On “Down To Go” Houck describes a conversation in which the accusation is thrown at him that he’ll “spin [his] heartache into gold,” and his reply is “I suppose, but it rips my heart out, don’t you know?” This more or less sums up Phosphorescent’s appeal; it’s rare to find a lyricist so honest and a vocalist so earnest, and when put into song it seems to Houck as if every word is vital and cathartic and necessary. Muchacho feels like the next link in a chain of anguish that is Phosphorescent’s discography. It’s not a thing I would wish on most people, but when it comes to Matthew Houck, long may the heartache continue, because it seems like there’s plenty more gold to be mined from those depths.