Orville Peck‘s debut album Pony offered a captivating avenue into a genre that wasn’t necessarily all that appealing in 2019 — outlaw country. Three years on, the genre has found new footing largely thanks to the unheralded excitement surrounding the masked singer’s (the good kind, lol) follow-up to his magnificent, understatedly dark yet liberating debut. Unfortunately, a couple of red flags threatened this excitement. Since the release of his star-forming debut, reservations have arisen, all tied to one big issue — the Canada-based artist has got his cowboy boots stuck in the mud of the mainstream.

Excuse my seeming pretension, but hear my qualms.

After signing with the music conglomerate Columbia two years ago, Orville was seen dabbling in the circles of Diplo, Noah Cyrus, and others within the Grammy-core crowd. Slowly but surely, the fringed mask began losing its once enigmatic allure. There started to seem something ingenuine behind the get-up; his reluctance to show face at first now seems revealing. Some have even suggested that the whole Orville Peck act was a mere schtick to begin with. Have they been right all along?

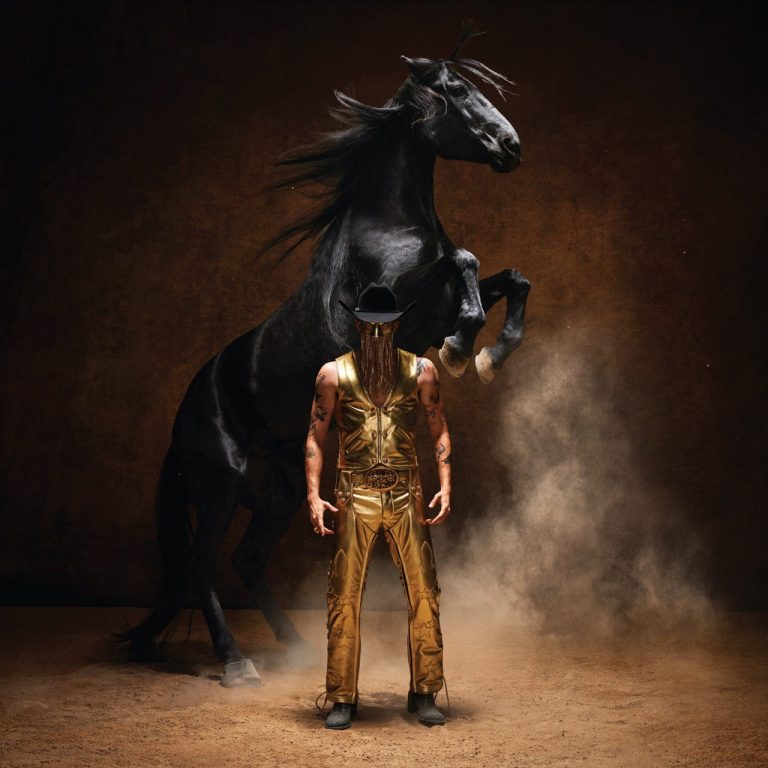

Flash forward to 2022, with a rather uninspired EP released in between, the mask of old has been programmed into the industrial-sized machine, ready-made to churn out copies, faux versions lacking the weathered charm of the original. The once-desperado with brooding bravado is now in danger of embracing the glib trappings of a depthless popstar with his sophomore record. As the follow-up to Pony, the title Bronco seems to imply a natural maturation – but things aren’t always what they appear. Instead, the King of the Rodeo has been stripped of the raw and sincere draw of a weathered, albeit sensitive, brute, which he so effortlessly conveyed just a few years back.

Though undeniably infectious, mostly floor-stomping, and right up the alley of those who are merely intrigued by what the outsiders of country music could offer, the three ‘chapter’ Bronco flaunts a sheen that’ll take time to get behind. But don’t get too close; you won’t find much except a horse’s ass. Seriously, the stories and sentiments expressed are far too slight, predictable, and melodramatic to have much effect.

Take the vapid longing of “Outta Time” of Chapter 1, for example, where Orville fronts his well-worn nomad persona, but this time he scales the not-so compelling regions between Southern California and Reno where the Wild West is no longer. Sure, the flings of gay lust between stops are a rather new-ish wrinkle for the genre itself (within the mainstream that is), but the song’s thematic core of a snide renegade shooting from a seductive hip is anything but contemporary.

The same issue plagues even the album’s most brazenly rowdy moments. The infectious jangle of “Lafayette” will get cowpoke swaying and shuffling their feet. But as Orville growls, strutting with confident showmanship, “I recall somebody saying there ain’t no cowboys left / Well they ain’t met me,” feels odd considering the overt caricatured cowboy clichés, good and bad, that he draws from throughout his music and then dresses his image with. “Any Turn” is spun with a similar triteness, as Orville bemoans his position of observing the world of popular country music from the outside looking in. But is he really an outsider anymore? When you get to a stage where Shania Twain is featured on your album, and your music enters the Country Billboard top 50, it’s safe to say you’re part of the club now, buck-o.

Not all is without depth on the bucking Bronco; there are a couple of moments where Orville’s lyrical gift does pop its head through the door to say hello. “The Curse of The Blackened Eye”, made evident by its title, is about the trauma of an abusive relationship. But you wouldn’t know it with the confidence and conviction in which he unleashes rather drab statements like, “I sat around last year wishing so many times that I would die…” or “True, it follows me around / Nothing to lose / Lost it all anyhow.” These poetically rendered realizations of lingering trauma should be sung with a most despondent and hesitant tone, but Orville insists on keeping listeners on their toes. It’s a tactic he deployed often and successfully on Pony, but there every story and emotion rendered was mysterious for mystery’s sake, whereas here it feels like an obvious ploy for attention.

“Kalahari Sky” is another rare moment where Orville’s truth and songwriting talent shines through the veneer. With his backing band playing as passionately as ever, Orville tackles the cowboy motif with tongue-in-cheek and a tear rolling down it to boot. While dotted with images of the badlands, spitting chew into a jar and roaming recklessly into the sun, he makes it clear that these cultural contours don’t matter deep down inside for this artist. Being a cowboy and making country music is about being daring and wild at heart, so he trades his horse in for a Kawasaki motorbike, and instead of riding off toward the great plains of Kansas, he detours toward the golden horizons of Mendocino or wherever in this great big world his heart desires to be.

With soul-crushing and resonant moments such as “Kalahari Sky”, “The Curse of The Blackened Eye”, or even the somber-hued “City of Gold”, why then is half the record littered with so many comparably shallow offerings? Fans of his magnificent debut will be disappointed, and those who couldn’t resonate with this cowboy on Pony, hoping to do so this time around, might come away even less impressed with Bronco.

When Orville’s words fall flat, listeners can at least find satisfaction within the deep bellow of his voice to carry their lowly and weary heads. Listen to him belt, “Wouldn’t it be swell if I could get things off my chest?” and try fighting off the twinge of inspiration that’ll arise in your heart as his baritone soars a couple of registers higher through the rootsy bluegrass of “Hexie Mountains”.

But, unlike Pony where every vocal performance was a smashing hit, some instances on Bronco will make you wonder if Orville’s producers really understand his unheralded ability to carry a song with his voice. But should we be surprised? It’s Columbia Records. Orville has always had an incredible voice, crossing a space that conjures the ghosts of Elvis, Merle Haggard, and even Roy Orbison. It’s the type of voice that needs to be pronounced in all of its perfection and personable imperfections, but tracks like “C’mon Baby, Cry” encounters Orville’s snarled and rough twang drowned out by the instrumental and compressed to a disgusting degree. Hearing him cross an uncomfortable falsetto threshold as he sings “Let me see you cry” sounds painfully manufactured and unnatural. You can’t blame the artist here though; he’s more than proven he can deliver the rangy goods, but the choices of those involved with the final product dampen what would have been a solid song otherwise.

Bronco should have been Orville Peck at his best self. Pony promised much more than what we have in front of us: an exaggerated and unflattering portrait of an artist shrouded in genre and aesthetic clichés. There’s nothing wrong with being a mainstream artist by any means, but once that world has been presented, it’s imperative to ask: how does one stand out when the glamor takes hold? The get-up and added varnish might be finally running dull for Orville. He remains a fabulous fashion icon, yes, and the queerness of his music is still radiant and charming as ever. But on Bronco, the country cowboy wink and nod seems to have lost its elusive essence. He has to do away with the platitudes and vagueness, both musically and lyrically, to be remarkable moving forward. There’s so much talent and story hidden behind the mask, but this album isn’t Orville Peck at his truest.