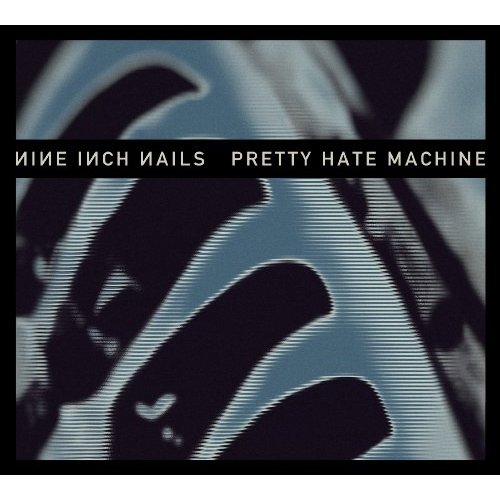

It’s hard to talk about an album like Nine Inch Nails’ Pretty Hate Machine in a modern context. On paper, it has all the elements of a classic record that merits rediscovery: it was one of the first albums to make industrial music accessible to pop audiences in a big way; it launched the career of Trent Reznor, who at this point has to be the most artistically relevant of the ‘90s alt-rock survivors (I mean, who’s his competition? Chris Cornell? Eddie Vedder?); and it contains a few of the most enduring rock-radio staples of the last 20 years. Add to that a long, complicated history of ownership and legal disputes that kept the album from being reissued for years, and you have the recipe for a seminal album by a hugely important act that needed only a sonic update to cement its legacy.

But here’s the thing about Pretty Hate Machine: it really isn’t very good. It’s that simple. It’s not Reznor’s fault, either. This was exactly the kind of album a 23-year-old Ministry fan with girl problems should have been making in 1989, and the deeply tormented “Head Like a Hole” and “Something I Can Never Have” struck a nerve. But while Reznor’s other pre-sobriety full-lengths, 1994’s stone classic The Downward Spiral and 1999’s eternally misunderstood The Fragile, only get better with age, Pretty Hate Machine in 2010 plays like a collection of mediocre Depeche Mode outtakes.

“Terrible Lie,” “Head Like a Hole,” and “Sin” were permanent fixtures at NIN shows right up until Reznor put the group on hiatus last year, and with good reason. Given the proper full-band treatment, these songs are pretty ferocious. Listen to the studio version of “Terrible Lie,” and then to the one on NIN’s excellent 2002 live album And All That Could Have Been: the original is so toothless by comparison that it’s almost laughable. And these are the good songs. Reznor’s diehard fans swear by this record, but is anybody going to tell me with a straight face that “Kinda I Want To,” “That’s What I Get,” and “Ringfinger” aren’t the most embarrassing things he’s ever recorded?

The new remastering job is an upgrade from the original in that the guitars have a little more bite and the drum machines have actual dynamics, but the synthesizers date themselves painfully to the late ‘80s on most of these songs, something Reznor has basically admitted in the last few years. And his lyrics—let’s not even get started. Reznor’s never exactly been Lennon, but he was eventually able to turn his heavy-handed introspection into something at least reliable. This stuff is seventh-grade poetry: “How could you turn me into this?/After you’d just taught me how to kiss/I told you I’d never say goodbye/Now I’m slipping on the tears you made me cry.” Yeesh. I can’t even fathom how embarrassed Reznor probably was when he went back into the studio to remaster this album and realized that millions of people have heard these words coming out of his mouth.

But this is all hindsight. Just because an album doesn’t stand up 20 years after it was recorded doesn’t mean it didn’t serve its purpose at the time. Reznor truly mastered the recording studio when he made the still-astonishing Downward Spiral five years after this album; here, it’s painfully clear that there’s room for improvement. The only added track, a cover of Queen’s “Get Down Make Love,” is something most NIN fans already have, but it’s better than most of the songs on the proper album, and the ones that aren’t embarrassing can be heard in far superior versions on any number of bootlegs and official live releases. NIN completists could do worse than to pick this up for the improved sound, but I can’t see how this album would be of much use today to anyone who hasn’t already heard it.