Four albums in, you start to wonder how far Rotterdam quartet Lewsberg can still stretch their minimalist modus operandi without repeating themselves. Here’s the thing though: repetition has always been Lewsberg’s calling card anyway, so by virtue they’ve made themselves immune to the whole ‘repeating themselves’ trope. Which is, honestly, quite hilarious. Repetition has been part of the point since the band’s beginnings, the tether in which each subtle shift in melody – or lack thereof – is taken heed of, allowing syllable and phrase to tremor through your consciousness.

The earlier records, the self-titled Lewsberg and In This House, drew comparisons to the likes of Galaxie 500, Gang Of Four and – quite obviously – The Velvet Underground. Though resolutely minimalist even back then, one could still detect the toils within Lewsberg’s threadbare songwriting dynamic. The repetition employed in “The Smile”, for instance, still felt volatile, like a clock winding down to zero. Even the song’s heavier parts were played stoically and rigidly, the band showing no performative fireworks that accentuated the quiet-heavy dynamics. Furthermore, Lewsberg’s refusal to engage in pretentious stage pantomime made them stand out from their peers.

If their self-titled album captured a whirlpool of change in the city of Rotterdam, In This House sounded like an enshrinement of a city that once existed before it became overrun by quote unquote prosperity. Songs like “Left Turn” and “The Door” embraced the unfettered discord and wanton ugliness that was once rife in its restless building and breaking. It was as if within those uneasy notes and silences, the clamor and commotion of days past preserved like an epitaph etched into a gravestone.

So where do Lewsberg go from there? As much as those first two albums were informed by their base of operation, the band are too shrewd and circumspect to perpetuate their own ‘myth’, for lack of a better word. Their impromptu LP In Your Hands – released in 2021 during the latter half of the pandemic – signified essentially ground zero for Lewsberg: a solemn meditation, rummaging the wreckage for hints of reprieve. It was an exercise in ‘less is more’ for a band already much defined by a ‘less is more’-ethos: it affirmed that Lewsberg, even at its smallest and most stripped down, could sound so captivating within its modest use of instrumentation. If the first two records captured a cacophony going extinct, In Your Hands embraced solemn reflection.

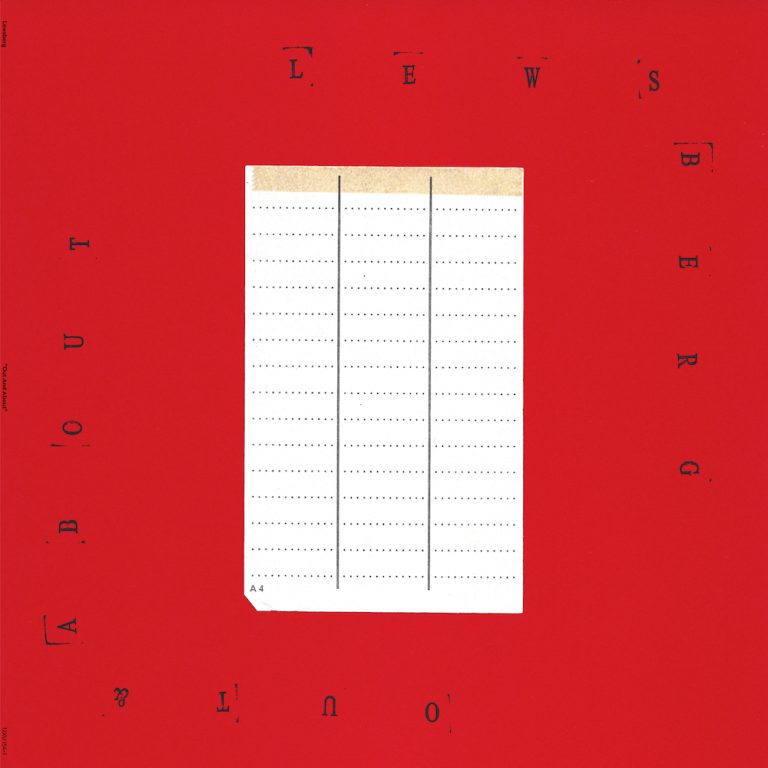

The keyword for Lewsberg’s fourth long player, Out And About, seems to be conversation. The band – which has steadily gained international notoriety over its seven-year existence – adjusts its scope toward a ‘bigger world’ before them. Of course, what makes sense for most bands is often counterintuitive for Lewsberg. After releasing an album containing their most sparse recordings, it wouldn’t exactly suit them to suddenly roll out a grand parade.

Out And About is still a very minimalist listen, but decidedly more outward peering than its predecessors. The addition of drummer/vocalist Marrit Meinema – who was part of the Frisian provincial DIY-scene surrounding The Homesick and Yuko Yuko, as well as cheeky Rotterdam punks Venus Tropicaux – adds a fresh, wryly buoyant voice into the mix. Meanwhile, Klein left Rotterdam for Groningen, with the other half of Lewsberg – Arie van Vliet (vocals, guitars, violin) and Shalita Dietrich (vocals, ass) still based in Rotterdam.

One early conclusion after hearing Out And About, a Lewsberg with one leg outside of the Dutch port city still sounds like, well, Lewsberg. Their music still eschews easy sentiment, the music’s subtle idiosyncrasies patiently revealing themselves through its lurching repetition. On Out And About, however, there’s a giddiness and playfulness straying off like an odd loose thread escaping their economical tapestry of sound. Opener “Angle Of Reflection” seems to interrogate that specific Lewsbergian insistence of being cast-iron and matter-of-fact in its storytelling: “What a second look can do to a fact,” Dietrich speak-sings.

Out And About finds Lewsberg reassessing what made them tick in the first place. “An Ear To The Chest” shocks the listener into a state of alertness, Klein’s squealing guitar sounding almost like an alarm clock short circuiting. There seems to be less staring-at-the-void disquietude, more incentive for the four musicians to reciprocate within the liminal space of their songs – reading and reacting – and as a result, there’s an immediacy radiating throughout these 11 tracks.

With its jangly strum – reminiscent of The Feelies or Naive Set, another excellent Dutch outfit Van Vliet once briefly played in – “Without A Doubt” might be the most sunny, optimistic-sounding Lewsberg track we’ve heard. As a counterweight, Klein’s guitar plucks are discharged with the constitution of a malfunctioning office printer. In order to behold color and beauty, there has to be a sobering backdrop. Every dainty picture needs a sturdy functional frame, after all.

But it’s hard to ignore the virgin jolts of joy sprouting from Lewsberg’s dreary backdrop, like tiny blades of grass peering between tiles of concrete: easily trampled on, but still reaching upwards. The agreeable chug of “Communion” and the Meinema-sung “The Joy Of Spring” express a modest wonder of natural cycles and spirituality, though conveyed through Lewsberg’s ever-imperturbable, inquiring lens. Just as well, a more upbeat, agreeable Lewsberg still doesn’t translate to a band willing to land on sapid truisms. On “Going Places” Van Vliet deadpans that “Everyday you knock on a door you’ll never go through”, for Dietrich to later sing “You haven’t said a single word.”

The song’s protagonist seems to not be going anywhere, forever on the threshold of not deciding: it’s kind of funny when you consider that the violin part was a melody that had been brewing in Van Vliet’s head for several years, only just now ending up on a record. On the hushed lamentation of “There’s A Poet In The Bushes”, the poet in question keeps the page empty, even though he’s inspired to write. Instead, he finds solace in daydreaming about things he could summon into existence: “If I want the rose to bloom, the rose blooms.”

Out And About strikes as a series of stories cut off halfway from their conclusion, leaving the rest to the listener to fill in. It’s probably the most generous way Lewsberg has applied their trademark pragmatism to their music. They’ve always had a unique gift for painting vivid scenery with even the simplest, most barren of means. But Out And About exudes a wanderlust not per se bred from documenting the journey, but from simply clearing the path ahead. Indeed, Lewsberg’s signature emptiness has never felt so fertile with possibility.