A WORD FROM THE EDITORS: As the new album by The Smashing Pumpkins is a somewhat dense release – at 33 songs across 2 hours and 18 minutes, a sprawling sci-fi concept and a 33 episode podcast series to explain both – the reviewer has decided to present his perspective on the record in three chapters. This choice has been made so as to adequately represent each aspect of this monolithic concept record, while also allowing the reader to not lose focus on each individual subject and skip forward (or sideways) when an element isn’t interesting. Because frankly, there is too much to talk about for a casual review to grasp it all.

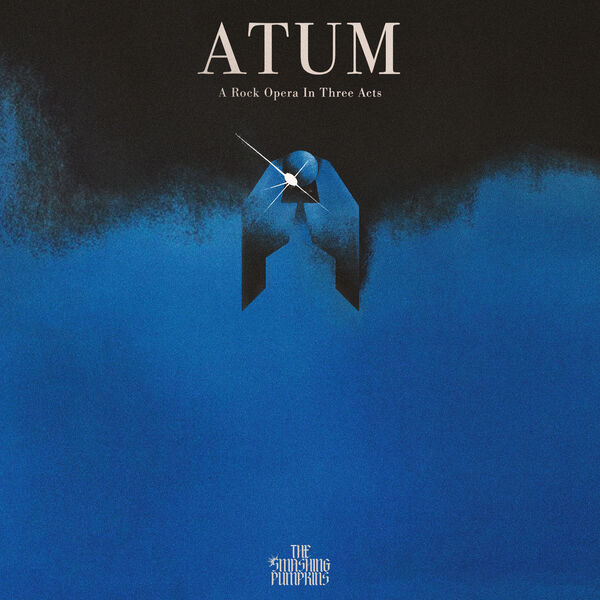

We hope you find this essay about ATUM: A Rock Opera in Three Acts informative and its presentation appealing.

PART 1: THAT WHICH ANIMATES THE SPIRIT – The story of Shiny.

It’s impossible to fully embrace how other people see who we – individually – are. Part of that is, obviously, because we all are stuck way too much inside of our heads, ruminating about our actions as much as on those of the people we interact with. But another is because everyone on the outside lacks the full context of all the small moments that make us who we are, the intricately woven tapestry of our past and present that becomes one.

Now, transport this realisation – that we can never fully understand another person – onto somebody who’s a genuinely self-determined maverick that’s been analysed and interpreted all his life, misunderstood constantly and been framed by a body of work that spans decades and touched millions, yet has been derided as the ponderous vision of an ivory tower loner. You might have an inkling of how frustrated Billy Corgan has been with how the world has perceived him.

Easily one of the most interesting and certainly the strangest figure of the Gen-X rock stars, Corgan has chosen a path of contradictions and surprises. He pioneered the metallic marriage of shoegaze, cold wave and electronica that Drab Majesty and Boy Harsher now embody on his 2005 solo project TheFutureEmbrace, predicted America’s political and social schizophrenic hysteria with 2007’s powerful and lumbering Pumpkins album Zeitgeist and dove headfirst into chromatic synth-pop with 2020’s CYR, a heartfelt album that was for the most part an enjoyable and vivid cyberpop experiment.

Given the somewhat muted response to that last album (the cold aestheticism of synthetic sci-fi landscapes wasn’t really what most listeners wanted in their lockdown-laden lives), it’s impossible to fully analyse what devil whispered into Corgan’s ear, or angel sung inside his dreams, to make him conceive ATUM: a rock opera and sequel to the artistically gargantuan Mellon Collie and Machina double-album projects that would continue their narrative (what?) and present the recently reunited Smashing Pumpkins (minus D’Arcy, who, well, is quite an important omission…) at their most artistically diverse and stylistically daring.

So here we are, with over two hours of music and the story of Corgan’s latest resurrection of his musical avatar: “Shiny”. Last we heard of Corgan’s dark twin, he was still called Glass, a cyberpunk goth prophet who thought he heard the voice of god on the radio and grappled with a dystopian mega-corporation record label that implanted people with micro-chips so they could hear music and be tracked simultaneously.

If you don’t remember this from Machina 1 and Machina 2, don’t worry, it’s mostly bits and pieces scattered around the meta-text of those projects: sprawling websites that are tinted in occult and alchemical imagery, dense poetical narratives hidden in the vinyl version now preserved on forgotten blogs, and three episodes of a never finished animated series. Point being, it was a dense and cryptic story, rich in the paranoid post-Matrix aesthetic of the late 90s, where the end of the world – and the death of rock – seemed eerily believable.

Mellon Collie, meanwhile, barely introduced a character named “Zero”, whom Corgan merely created as a persona to underscore his public image of volatile megalomania. Granted, Corgan has admitted since that the Machina concept was elusive even to him, conceived during a particularly dark period and executed with an already frail group of musicians breaking apart. Thus, his Shiny-cycle could well repair all this, yet the narrative makes it much more complicated.

At the start of ATUM, Shiny has been banned into space, where he drifts aimlessly, finally deciding to steer his ship into the sun. Unknown to him (as he never met her), mega-fan June is traveling nearby. Shocked by his suicidal action, she commits to follow him to certain death, and along with her an armada of other ships. Meanwhile, she broadcasts to Earth via the internet, inspiring a young girl to become a fan and spreading the gospel of rock among the ignorant youth. Miraculously (we never find out why), Shiny decides to do a last second 180 and evades certain death, while June and the other ships burn up.

Back on earth, a dystopian totalitarian regime is hunting the ragtag group that spread Shiny’s music, concluding in a moment that’s directly lifted off Michael Caine’s final scene as Jasper Palmer in Children of Men. Soon after, Shiny lands and is mostly a blank slate who just… kind of doesn’t get what all the fuss is about and plods along with the plot. After uniting with a sex robot that houses his “true essence” (yes, this happens, just wait and read on), grumbling at the armed totalitarian forces of “The XNI” and evading an assassination attempt by his newfound mega-fan, Shiny and the robot decide to just drift back into space. The world just doesn’t get them.

Following the story through 33 weekly podcast episodes, it’s evident that it’s a patchwork of pop-cultural influences, socio-political misunderstandings and Gen-X boomer paranoia. Shiny never develops into a full character with motivation and never has anything to do or say past his own befuddlement with how people respond to his existence. The totalitarian regime lacks the satanic cyberpunk glow of the Machina-era villains or the demonic utilitarianism of the Agents in The Matrix, while the rest of the cast only exist as mirror surfaces that reflect their own desires of who Shiny should be onto him. Yet it’s never clear what his supposedly oh so subversive and provocative politics are that sent him to exile in the first place; Shiny and his views were simply too real. Yes, to fully decode what’s going on here, we need to surgically deduce info from Billy Corgan’s Podcast, which tells it all…

—

PART 2: BEYOND THE VALE – The Billy Corgan 33 experience: the podcast.

The Thirty-Three podcast is the latest, the ultimate in Billy Corgan’s attempts to find an adequate format to communicate his innermost thoughts, his true beliefs and absolute stances on all things Pumpkins and Smashing. It follows a blog, attempts at an auto-biography, a myspace diary, various Instagram live streams and album deep-dive videos. Given that none of those stuck around, seeing him finally complete a conceptual venture that has him talk about pretty much every single era of his long artistic journey is really heartwarming. Here, he expands on his artistic process, the deep emotional tie to projects that deserve re-evaluation and opens up about his most personal experiences. It’s a wild ride, peppered with random guests and salted by occasionally insane moments, which give a somewhat sombre impression of ATUM‘s emotional core. Examples abound, and editing them down is a Sisyphean task as there are so many.

One of the leading themes of the project is Corgan’s disillusionment with modern times. A romantic at heart, the Chicago native has made no mystery of his nostalgia for a golden era of art deco arabesques and gentle kindness, which directly contradicts his Neuromancer-inspired cybermetal that permeated the Machina era. Thus, Corgan recurringly laments the state of cancel culture and censoring social media platforms, yet his words repeatedly reflect deep misunderstandings about these (and other socio-political) dynamics. At one point he inquires with his co-host Kyle (the secret star and dramatic core of the podcast) if he would rather a world that is deeply regulated and sanitized, but would offer him and his loved ones security from violence and harm, or a world without censorship and regulation, offering total freedom for the price that bad things could happen any day. Kyle chooses the regulated world, and Corgan retorts if he understands this would very likely mean this very podcast wouldn’t exist and if he would be fine with that. Kyle just shrugs and responds immediately: “Yes.” Corgan is baffled, and will return mockingly to this point in the future.

OK, so what about the podcast is this upsetting and revolutionary it could alarm the authorities? Turns out: not much.

Corgan thinks “cancel culture” is a dynamic based on bullying and a symptom of societal imbalances that enact mob-rule. Not a very revolutionary thought, given Mark Fisher already said everything noteworthy on this topic a decade ago in a brilliant essay. Later, the musician ponders on America’s political compass, and ruminates on the fact so many despise Trump’s policies, while Joe Biden has voiced his dissent with gay marriage in the past. People say he changed his opinion, broods Corgan, but wake up Libs, Biden is just saying what you want to hear to gain votes and influence. Well, that’s no news either, given how many prominent leftists and Bernie-supporters have voiced their dislike for Biden and viewed their vote as a strict means to an end of the Trump era. Maybe Corgan should guest on the stream of prominent leftie Hasan Piker to update the compass of public (leftist) opinion on the democratic party and liberalism as a centrist fantasy. Things get even more confusing when Corgan decides to discuss the recent accusations of Satanism at the Grammys. Shocks like this, Corgan opines, happen when there is a cognitive dissonance between the music that ‘the suits’ in major label exec offices deem agreeable to reward in such award shows, and the real music that the real people on the street listen to. When Kyle wonders aloud if these illusions of demonic ritualism aren’t just Catholic panic based on a bunch of goofy costumes, Corgan retorts with a blunt “I don’t think so” and brushes the very correct analysis aside in favour of uninformed presumptions.

These occasions are important to the discussion around ATUM because they reveal the narrative’s weak link in its allegorical approach: Shiny is so baffled by a world that has become absurd because Billy Corgan has never properly investigated what the actual dynamics of our contemporary society are. Where, in the late 90s, he accurately deduced the corporate overreach of monopolistic institutions and thus was able to predicted the structural degradation of the music business, he hasn’t understood that the trappings of cancel culture have been widely disseminated in the sphere of left-leaning circles, that neo-liberalism is gradually falling apart and a new type of political intelligence has shifted the public opinion to more socially-minded attitudes (explaining the popularity of AOC and Bernie Sanders as well as that of leftist public figures) and that fringe movements often engage in creating a mythology of conspiratorial thinking towards cultural progression. Thus, it’s not culture that’s become absurd, but Corgan who has become isolated in his own mind, not unlike Glass 23 years ago. Trying to cling to centrism, Corgan created a modern fable, where his fans are extremists that see him as a Judas-like figure who betrayed his true calling and won’t deliver that which they ask for – be it hard rock or the simple truth.

What’s so weird about this is that Corgan himself is closer to social policies in his daily life than he realises, graciously supporting his fans with gratitude and kindness. His tea-house is involved in the local community and provides for those in need with base activism. He’s also outspoken in his support for trans- and queer individuals and engages himself against bullying and racism. At the same time, it’s notable he discusses pseudo-anti-censorship-warrior who deletes anyone he is annoyed by off his platform, brain-chip-implant-inventor and crybaby Elon Musk (a nepo baby who ruins every company he’s bought himself into and randomly blurts out regressive bullshit) repeatedly, without ever mentioning MisterBeast, whose latest involvement of supporting deaf and blind people with medical procedures and massive donations set the internet on fire: Corgan picks his hot topics from news headlines without involving himself in the actual substance of and facts on those topics. Like Shiny, he floats up there in space and barely communicates with those who have the proper insight into those dynamics, only engaging with the headlines of the very institutions he disavows. In the end, he still seems grumpy about taxes, and defends capitalism even tho he succeeded not because of it, but in spite of it, as the dynamics of neo-liberal dehumanisation and music business ignorance are the direct embodiment of commodification. He defends the very structures that are the byproduct of what he hates the most.

And this is where things get interesting: when speaking about criticism as a factor in his life, Corgan’s voice rises. I’ve never heard the man as angry as when he addresses how unfair fans, journalists and gatekeepers in the industry have treated him, including when he mentions how they derided his Teargarden-era track “A Stitch in Time”, a wonderful acoustic song that demonstrably was received very warmly among fans upon its release (the message boards dug up the threads, of course, supporting Corgan’s claim how neurotic their pedantic tendencies can be). It’s in those moments where it becomes clear that Corgan has written ATUM as a forceful counter push – less directed at dynamics he (clearly) misunderstands, and more as a means to free himself from demons which, for decades, have eaten at his ego and digested his reputation. After all, the central image of a lone man that flies into the sun goes back to 2009’s “A Song for a Son”. Corgan is his own Icarus, who flew too close to the sun and fell to Earth, only to decide to throw himself into the sun, this time out of spite. But then, something beckoned him back, to create the Shiny cycle…

—

PART 3: THE GOLD MASK – the 33 songs of ATUM

ATUM expands over three discs, each of 11 songs. Recorded in sequence, they not only narrate Shiny’s story, but also document Billy Corgan’s evolution throughout the project – which is quite notable. In fact, with the entire project now finished, it’s painfully obvious that the record demanded a lot of Corgan and the Pumpkins as a unit.

The first act especially is rough. Much of the writing here seems uncharacteristically meandering, similar to the weaker, hymn-like CYR tracks, like “Dulcet in E”. Structures seem not quite sharpened and melodies often generic. Corgan also indulges in a more elaborate vocal singing style, which plays with vibrato and jumps cadences often, excluding the Johnny Rotten-like punk raspiness his 90s intonation is so well known for. Many of the songs also use synthesizers that sound – especially in direct comparison to the monochromatic iciness of CYR‘s majority – strangely whimsical and goofy.

Same is true of the lyrics, which already spawned many memes: Billy Corgan indeed has come to roust us, this time. And then there’s the felt absence of James Iha and Jeff Shroeder, and Jimmy Chamberlin’s odd passive style here: countless songs are reduced to him playing kick-snare-kick-snare, like a drum machine with no dynamic. But the chief offender here is the production stylisation of Howard Willing. At one point in the podcast, Corgan explains Willing would furrow his brow at anything that sounded like “the old Pumpkins” and lament the production style of 60s records (which misses the whole point that the era is so beloved and timeless precisely because of the heightened atmosphere of analogue recording style and studio ambience). Coupled with the unemotive vocal style and snare-kick drums, there’s a lot of Sisters of Mercy on ATUM, which isn’t a good thing at all.

Most of this first disc sounds surgically processed – “Embracer” or “Where Rain must Fall” thus end up as strange post-Duran Duran synth-pop amalgamation, where the writing would demand singer songwriter intimacy. Meanwhile, the rockers “The Good in Goodbye” and “Steps in Time” suffer from the same limp energy as “Wytch” a few years ago, an almost artificial Rock sound with no room ambience and Corgan delivering the vocals without emotional register. And the “psychedelic” songs that flirt with prog, like “Butterfly Suite” and “Hooray!”, just seem random and hokey.

Thankfully, a few moments stand out. “With Ado I Do” is pleasant as electronic ballad. “Hooligan” is emotionalyl detached, but is reminiscent of the strange industrial glow of Taylor Swift’s Reputation-era and works well enough. “Beyond the Vale” isn’t rousing, but memorable for its decent refrain. The one true standout here is “The Gold Mask”: even with the generic kick-snare beat, its melody is memorable and beautiful, while the refrain is classic Corgan. There’s also the sense of melancholic nostalgia all over its lyrics and tone, making it a genuinely very good song. Finally… I don’t hate “Hooray!” It’s bad, sure, but also a conscious polka goof that ends with a minute of Mort Garson-like synthesizer tomfoolery that’s just too cute not to smile at, lighten up nerds!!

Act 2 opens with the very nice “Avalanche” – another singer-songwriter song that slightly suffers from being injected with tons of electronic arabesques. It’s decent, but could have been a new “Galapogos”, which is also true of “To the Grays”, whose humble structure is quite listenable, and the atmospheric “Every Morning”, which really could have dropped the kick-snare formula. “Empires” meanwhile has Corgan emote the title as “Empaahs” and sleepily delivering what should have been an angry and emotional performance – not as bad as “Wytch”, but still fairly limp and reeking of A.I. songwriting. Lead single “Beguiled” is as dispassionately performed as can be, with James Iha’s solo just climbing up the guitar’s arm without any texture or flair. “Neophyte” is, according to Corgan, a song that will stay with fans and grow as a favorite, but is a repetitive and wholly unremarkable synthpop downgrade of “Shame” off ADore. The odd XNI hymn and Black Sabbath homage “Moss” includes prominent meowing (!!) by background singer Katie Cole and isn’t bad but not great either, which is also true of the synthetic “Night Waves”.

Still, Act 2 is a little more remarkable than Act 1: “Space Age” is playing with odd synth tones and using an interesting mix of drums and synthesizer washes, kind of an upgraded “Spaceboy”. Again, it’s the tail end which stands out. “The Culling” starts off slow, but builds to rousing pathos and includes a sudden appearance of a really poignant New Order-like bass line, finally exploding into the album’s first real climax. Corgan’s resigned tone here hits the mark and finally communicates some genuine emotion.

And, speaking of, something interesting happens with “Springtimes”. Corgan recorded the song the day he got news of his father’s death. Anyone familiar with the complicated family dynamic behind the two Williams recognises that this is a cataclysmic moment for Corgan, and while the song was written before, its sombre lyrics and heartfelt delivery are a sudden shock on a record that is often emotionally distant. It also features a unique moment of fateful accident: recording a solo on a stand-in guitar after learning his father was not dead but admitted to a hospital and still alive, Corgan was struck how good it sounded. When his originally desired guitar finally arrived, so did the news of his father’s death. In a moment of somber defiance, Corgan recorded a second solo and finished the song. Realising that both guitar tracks harmonise beautifully and represent the familial and musical relationship to his father, he overlaid them, generating a magical touch familiar from the ode to his deceased mother, “For Martha”. It’s simply sublime, a track that lives up to Corgan’s high ambitions.

And something indeed seems to have changed inside Corgan going forward: gone is the dispassionate vocal tone and isolated synthetic sound on Act 3, which could be read as Corgan shifting ATUM into a treatise on the stages of grief. “Sojourner” is a little mellow and meandering in its almost eight minutes, but Corgan finally shows a bit of involvement here, while rocker “That Which Animates the Spirit” finally has a bit of angry expression in his voice and guitar line, and thundering Chamberlin drums too.

“The Canary Trainer” is OK enough, thanks to additional texture, but the real punch is the grim “Pacer”, which builds gradually into a stomping psychedelic synth pop anthem that would work well on a Depeche Mode or Drab Majesty album, only to explode into quiet ambient in its final minute. It’s still a little conceptual in execution, but it’s unashamed of itself and deserves to stand besides “Eye”, “Waiting”, “Save Your Tears” or “Here’s to the Atom Bomb” as among the best of Corgan’s electronic output. Representing June’s death as she burns up in the sun, it’s a pivotal moment in the narrative and it absolutely delivers. “In Lieu of Failure” follows with an immediate, heavy sound that resembles the classic Pumpkins work and is easily the best rocker on the entire album, while “Cenotaph” finally drops the snare-kick formula and allows the strong writing to shine.

Sadly “Harmageddon” follows in “Beguiled”‘s sound, but at least it’s compositionally a little more punchy and less plodding, with an actually exciting solo too. “Fireflies” is its opposite and sounds like Corgan has taken a liking to Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams”: it’s a clean pop song with an E-bow guitar and decent electronic drums. “Intergalactic” attempts to be the next “United States” and ”Silverfuck”, and while falling short (Corgan sounds a little exhausted here, in contrast to Chamberlin, who’s finally letting his creativity run), it’s a welcome inclusion on the project.

Sadly, the closing duo can’t live up to the rest of Act 3: “Spellbinding” is a synth-rock variant of Neil Young’s “Keep on Rocking in the Free World” that is destined to be a single, but simply too saccharine and optimistic in its pathos to fit on the project. It lacks the humble grace of “1979”, “Blessed and Gone” or “Pale Horse” – in other words, it will probably be a huge single and a boomer favourite, but too anthemic for its own good. “Of Wings” is considered the ‘credits song’ of the record, thus allowed to be a little stale, but its meandering writing and bombastic sound won’t fit the cutesy ‘old timey’ energy. It’s all over the place, and more of a welcome sendoff than a strong finish.

Still, the third act finally had ATUM spread its wings and nail its tonal ambitions for the most part, abandoning the plastic sheen of what sounded like overtly rehearsed and processed individual vocal and instrumental tracks that were quickly recorded and generically assembled into meandering material to represent a more confident and emotionally resonant – and even somewhat more corporeal and creative – sound, with the writing being allowed to breathe and Corgan’s performance becoming more human.

So, has Billy Corgan succeeded to roust us this time? Well, if we believe the gargantuan Pisces, then he’s happy with the result, proclaiming that if there’s 10 songs we dig out of the 33, he’s done his job right.

There’s a break here. Because 10 out of 33 is less than a third, making the inevitable score 33% or lower. I mean, why even release a triple album that only is good for one third? That just seems like trolling, so let’s head back in.

Corgan repeatedly asks guests what their impression of the public’s response to ATUM is during individual podcast episodes, and they always remark the same: that people seem to like it better as we get further in, past the halfway point, which Corgan seems to smirk at with a knowing ‘yeah, I expected that’.

Wait, is the man actually rousting us? Well, maybe not intentionally, as he also admits that this current iteration of the Pumpkins had a rough time finding its mojo. Which seems odd, considering both Shiny Vol. 1 and CYR had plenty of lovely material. Maybe it was the lockdown, maybe it was the lack of communal excitement on making a 33-song concept album that reflected on Corgan’s anarcho-capitalist reading of society (Jimmy Chamberlin is an admitted Bernie bro), or maybe – and most likely – Corgan himself created a narrative that ultimately lacked the arcane glow of the occult Machina or romantic passion and gothic sensuality of Mellon Collie, resulting in an artwork whose creator just saw more as an obligation than a gift, fully aware it sounded nothing like its two predecessors. Not even resembling the Tarot-fuelled, psychedelic Teargarden by Kaleidoscope or the nocturnal and chromatic TheFutureEmbrace, but kind of ending up in-between their figurations, it’s not as committed to perfectionism as we are used to by Corgan, instead resembling the strained Monuments to an Elegy in how its lack of quality control and sonic heterogeneity ultimately shape songs that needed an outside voice to deduce what these compositions need to truly shine. CYR already brandished a few of those instances (looking at you, “Tyger Tyger”, “Wrath” and “Telegenix”), but it was overall more convincing in its cyberpunk aura.

Likewise, the brooding assessment of Shiny as alter ego is mostly succeeding in showcasing how contradicting Corgan himself is. Here’s an artist who complains for 15 minutes about fans still pondering why “Set the Ray to Jerry” wasn’t on Mellon Collie, while he himself won’t stop talking about how omitting “Let me give the world to you” from ADore cost him double platinum, a man that still grumbles about the “Siamese Dream Zombies” that only like the band’s second album, but is also one of the most approachable and down to earth rockstars you’ll ever meet.

That’s why ATUM falters where Zeitgeist succeeded in its analysis of sociopolitical climate: Corgan is a socialist who thinks he’s a capitalist, a centrist with radical opinions that defy centrist power structures, a man who confuses the American Dream with “Might is right”.

There really is only one man in his generation still alive that rivals his mercurial spirit, and the comparison is inevitable here: Trent Reznor’s last work was also a reworking of past themes divided into three Acts of EPs, referred to as The Trilogy. Both musicians are edgelords that include electronic elements in their psychedelic understanding of rock and the parallels in their journey abound, from releasing albums online for free to paying for subversive online ARGs from their own pockets. But where Reznor doesn’t give a shit about cancel culture, Corgan won’t stop complaining about it, which is weird considering he’s always been allowed to follow his muse throughout his career, mostly with support from his core fanbase. Even going on Alex Jones or telling Howard Stern about a shapeshifter hasn’t resulted in any noticeable decline.

ATUM is the most controversial and strangest of all Smashing Pumpkins albums: a record that defies expectations but often disappoints in how prosaic and calculated it is. Just as it seemed to implode, it all of a sudden finds new meaning in a strong emotional core theme and nails the tonal split it confused for two thirds. It also spawned yet another record – Shiny Vol. 3: Zodian at Crystal Hall – which, from what has been made available, is an acoustic psychedelic folk album recorded live in the studio without much humdrum, and shows Corgan has already moved on to better things.

Yes, it’s good that we have ATUM, because it reflects a therapeutic era of Corgan bursting and putting onto paper what’s bothered him – and we got a handful of nice songs by the end of that phase. But it also is a testament that he’s at his best and most intuitive when he’s at his most emotionally raw, unfiltered, unrehearsed and most nakedly Pisces, with a strong voice guiding his creativity. The best songs here didn’t need a narrative about ungrateful fans and totalitarian liberalism, they needed Steve Albini or Flood to just sit the band down in a room together and go with the first take.