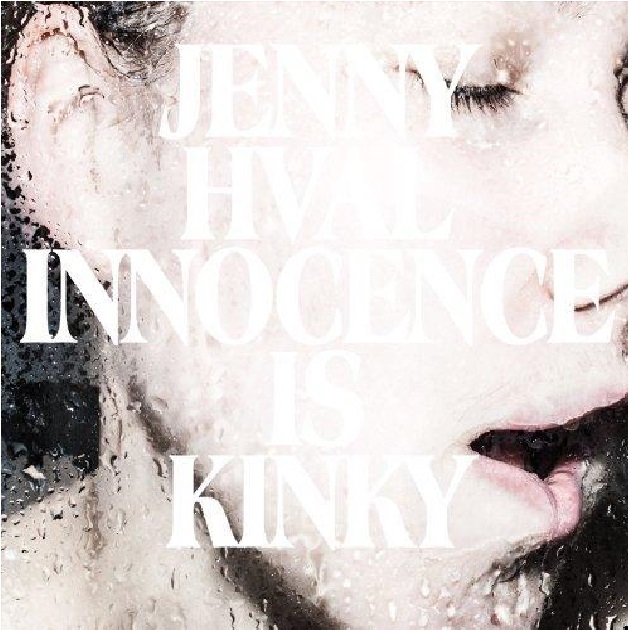

“That night, I watched people fucking on my computer.” When these are the opening lines to your sophomore LP, you’re setting quite the standard for yourself. Concerned, however, is as for as possible from how Jenny Hval sounds beginning Innocence is Kinky. Throughout modern popular music, more artists than one can fathom have structured song craft around that most blatant human desire: sex. Pop stars employ it to capture our basest tastes; Serge Gainsbourg made it an entertaining obsession, while the likes of R. Kelly make it deafening, bombastic celebration. Most immediately noticeable concerning Hval’s new record, however, is how far removed from any of these perspectives her curiosities lie.

She has no interest in selling sex. Delving into Innocence one can’t help but feel like they’re taking part in a, perhaps slightly perverse, experiment. If you’re to keep up with Hval, it’s time to don the goggles and head to the lab. Despite what the title and somewhat frantic album art might suggest, sex is not on show here. Rather, it’s her, and our, subject, to be poked and prodded.

Returning to that opening salvo, Hval sounds almost mischievous, but eternally clinical, statically removed from her own desires – a frustration she expresses moments later by literally shouting the word. Immediately following her pornographic line, she defensively, if slyly, justifies with, “Nobody can see me looking anyway.” She seems almost baffled by her own feelings, and it’s not hard to imagine this album being birthed from that same confusion, whether genuine or constructed. Certain aspects of the album represent Hval’s own perspective, but it’s most easily digested as the perspective of a character, a tool Hval is using to embody an impossible detachment.

None of this is to suggest the trek is so removed as to be dully uniform. To the contrary, the album is as scattered as our subject’s own splintered perspective on the matter, making the frenetic nature of album’s pulsating progression all too fitting. On “I Called,” Hval confronts her own unfulfilled desires, obsessing over her and an unnamed lover having “almost touched,” and that she, “wanted to say everything,” and attacking her own reservations. For herein lies one of the album’s great truths – that the very cautious, observatory nature of it is one if its creator’s short comings, and by extension, all of ours as well. She seems to shout it, at times: perhaps we’d all be better off going against our “better” sense at times, bleeding through in “I Called”’s key moment: “I didn’t give in.” It couldn’t be clearer that she should have.

From here the record shuffles into the telling interlude of “Oslo Oedipus.” One can picture Hval walking through still, muted streets by night, observing others in their own spheres of sexual isolation, taking the time to observe, “…people walk through the city, quietly, like friendly zombies…a slow burning flame of safety burns at the heart, but we cannot find it.” It nearly seems she’s addressing caution itself, yet, she cannot ‘find it’ any better than the rest of us, despite her chilly awareness.

Next up, on “Renee Falconetti of New Orleans,” Hval finally confronts sex itself, dryly observing, “It is an act of love, he enters you, through your body.” There is no joy in these words, however. All that’s to be found is an almost cruel sense of sarcasm when she muses, “For a hundred days, you are a virgin, or a young boy, you are not sure – I’m never sure. Innocence is just too kinky isn’t it?” Colder still comes, “Your hair is too short, and your face is too big, too close to be…anybody.” She’s considering the baseless fears we all feel, but has no pity for them, no time or patience for imprudence of desire.

As if to underscore the point, the next interlude “Give Me That Sound” is genuinely primal, right down to a nearly Tarzan-like opening cry, before Hval spews out a bizarre monologue concerning her mouth, giving it no more regard than others’ sensuality, treating it as some peculiar device whose sexual capabilities go against her own desired, if unattainable, quantifiable outlook. Even this contemplation feels too real for her methodical character, who, following the complicated dialogue, feels the need to suddenly snarl, “I don’t need anybody!” Following is “I Got No Strings” which, while allowing more emotion, insists on much the same idea with its Pinocchio-esque narrative.

The rest of the voyage progresses in much the same vain, with our heroine continuing to seek out the removal of emotion her scientific study demands, refusing to grasp she’ll never command an unbiased hypothesis. She imagines that, “Jean of Arc follows [her] around Australia,” a seemingly random, but fitting companion, considering her heralded resolute purity, and wishes herself as sexless on “Amphibious, Androgynous,” on which perhaps we get the closest to Hval speaking out herself, with the clarity of truth shining through in, “I tried to write love songs, but my words remain in my hands.”

They certainly did. Hence, this sprawling, at times impenetrable, but most outstandingly, engaging ramble was born. As things come to a close, the trudging forward movement of “Death of the Author” begins to bring the listener out of the tyrannical, nearly suffocating, world of the protagonist, finally giving into surging drums at its conclusion, followed by the quiet afterthought of “The Seer.” One almost feels as Odysseus, finally emerging to sail from the trials to return to be among men, only to be apart from them, in his own, forever more. In fact, to call Innocence is Kinky a sort of coldhearted sexual odyssey, or some equally twisted companion to Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (Bill Harford could really have used a listen), hardly feels a stretch. Higher praise than that, this writer isn’t sure he can give.