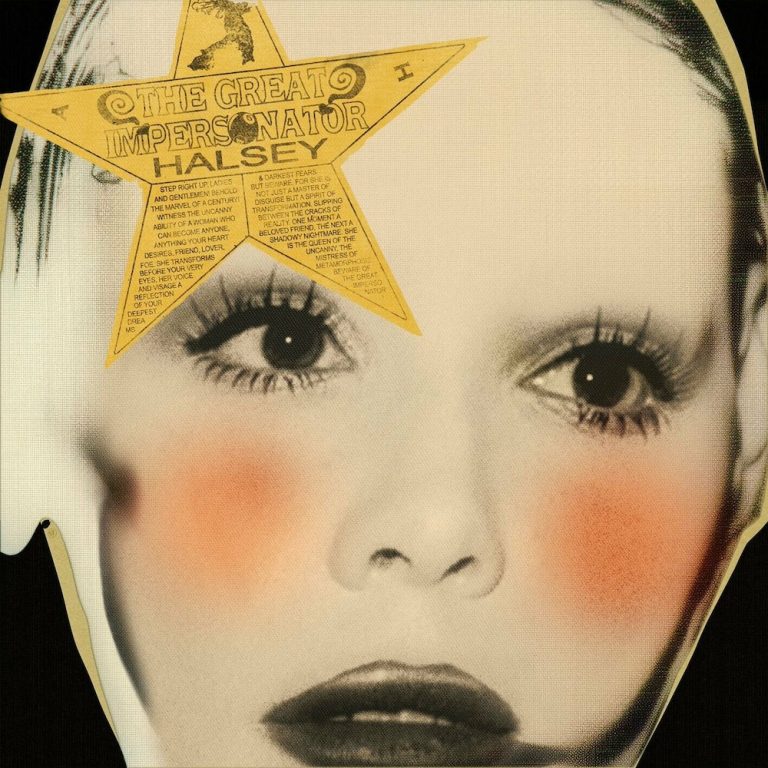

The Great Impersonator, the new album from Halsey, is an intriguing title for an artist who over roughly 10 years has transitioned seamlessly between distinct personas: the tortured ingenue of Badlands, the dystopian romantic of Hopeless Fountain Kingdom, the shell-shocked everywoman of Manic, and the grunge-goth priestess of If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power. Though Halsey tributes various artists as inspiring her new tracks, the compiled list functions less as a reference guide and more as a way of asserting a communal or aesthetic context. As image-savvy as Lady Gaga or Lana Del Rey, Halsey again crafts an engaging identity, presenting herself as part of a fertile heritage, drawing from diverse artists and genres. In this way, she plays implicit curator much as Beyoncé did on 2022’s Renaissance (though Beyoncé’s intent was to throw a post-pandemic soirée, while Halsey’s, at least in part, is to facilitate a moving memento mori).

At any rate, The Great Impersonator is rarely if ever overtly derivative. Prompted by her initiation into motherhood and struggles with lupus and T-cell disorder diagnoses, Halsey revels in signature vocal slants and melodic pivots, as well as her most nimble lyricism, bringing her latest persona to fruition: the wounded heroine or initiated survivor or, to stretch it further, the transcendent seer: a pop cross between Lilith and Tiresias.

“Ego” is a wildly infectious tune that portrays humans as inherently contradictory. The chorus is a riveting crescendo that recalls Jagged Little Pill-era Alanis Morissette, Halsey pointing out how self-obsession yields an incomparable high but can also result in irreparable mistakes, including relational wreckage. “Dog Years” exudes a more mercurial ambiance, built around a discordant mix that bolsters Halsey’s volatile delivery. Lyrically, the piece involves an intricate employment of the dog metaphor and subtle movements between perspectives. While Chat Pile declared (on Cool World), “I am dog now”, venting the rage that erupts from being oppressed; and ELUCID proclaimed (on Revelator), “The world is dog”, enumerating the barbaric realities of life on planet Earth, Halsey’s use alludes more to a mythic blend of self-loathing and self-aggrandizement, that space where damaged self-esteem intersects with narcissism.

This confluence of instincts (natural and twisted) is one that Nicole Dollanganger mines graphically on Natural Born Losers. Billie Eilish plumbs this domain intermittently, as do Olivia Rodrigo and Soccer Mommy (the latter with a melancholier leaning). This is also the milieu of poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, both of whom created a body of work founded on the empowerment that can arise from aligning with and rebelling against one’s own brokenness, sense of exile, and feeling of having been rejected (by someone or something).

The patron saint here, of course, is good old Lucifer, who was ousted from paradise for essentially being himself, and whose perennial motivation, largely unfulfillable, is to avenge this sublime and ongoing injustice (one might add that with humans, the rejector isn’t God as much as deific power expressed via institutions, parents, peers, lovers, and supposed mentors).

“Panic Attack” describes the fear that accompanies attraction, while airing Halsey’s health challenges. The melody wafts and flows, bolstered by a folk-rock mix replete with 70s-esque snare-drum emphases. On “The End”, Halsey tries to find confidence as she battles illness and self-doubt. Lyrically, she leaps from referencing an “ark” to “sailing on broken driftwood” to seeing her doctor “circling a drain”. Her melody is sultry, free-flowing but meticulously shaped. “Hometown”, meanwhile, underscores the singer-songwriter’s affinity for pop-infused Americana, unfurling a narrative that could easily be pasted into (and enrich) a John Mellencamp, Emmylou Harris or Taylor Swift song.

When she sings on “Only Living Girl in LA” that her “special talent … is feeling everything that everyone alive feels every day”, Halsey affirms the album’s ars poetica. The ability to access different parts of oneself is tied to the empathic impulse, which emerges from the experience of vulnerability, lack of control, even trauma. Again we see that the LP’s title is ironic, if not tongue-in-cheek. What Halsey accomplishes here, and with other work, is far from impersonation. She’s like an actor who can access a broad field of emotions and motivations; i.e., Whitman’s (and Dylan’s) “I am multitudes”. One could make the argument that there’s nothing a person can’t relate to or somehow incorporate if they process and to a degree heal from their own nightmares. Persona, rather than being an inauthentic construct, can operate as a compressed and purified representation of the self (or a part of the self). In fact, persona is potentially a more authentic representation of self, purged of the conditioning that dilutes and fragments so much day-to-day thought and interaction.

“Darwinism” spotlights Halsey as she again navigates a sense of being “the only outlier”. Sonically, the track integrates acoustic strums, noisy accents, and a resonant piano part. “Lonely Is the Muse” conjures the harrowing vibe of the 2021 album, replete with layers of crunchy instrumentation à la the Reznor/Ross production MO. The piece stands as a condemnation of the way in which women are still conditioned to fit in, support, inspire, rather than claim their own trajectories, despite various cultural and legislative shifts.

“Arsonist” features Halsey steering a stark but flammable soundscape as she offers what may be the most compelling verse of her oeuvre:

“You built a small container to keep all of me confined

I am water I am shapeless I am fluid I am divine

Somebody will love me for the way that I’m designed

Devastation creation intertwined

You don’t love the flames you just want them for yourself

Douse my head in kerosene, horizon into hell

And you smothered out the glow I grew for you but it was mine too”

The arsonist is morphed into an epic figure, a mysterious enmeshment of the desperado and an Old Testament God. “Life of the Spider (Draft)” similarly shows Halsey working with interwoven perspectives, adopting the motif of the spider to advance the imprint of an outsider, a sinner, a soul disconnected from nature and God. The piece occurs as a poetic-cum-diaristic take on the Job story, the singer musing, “How could I even think of daring to exist? / looking just like this I’m hideous”. This tendency to self-erase is reiterated in the closing title cut when Halsey moans, “I promise that I’m fine / … and put myself together like some little Frankenstein”.

The Great Impersonator brims with exemplary hooks, even as Halsey’s lyrical content exceeds pop norms. Many of her melodies could transfer to a bubblegum context, though her thematic surveys would serve as apt discussion points in a literary, psychology or philosophy seminar. Vocally, she’s at her most complexly sensual. The Great Impersonator stretches the bounds of pop while never snapping those fine tethers. Like Tiresias, Halsey survived her own “blinding”, emerging with second sight. Like Lilith, she exited the garden, refusing to be dominated by God or Adam (in secular vernacular, this translates to a denunciation of patriarchal and Christian-nationalist norms). She recognizes that loneliness is often one of the consequences of freedom, that art is an attempt to forge some semblance of intimacy. With The Great Impersonator, Halsey deftly wields the enticements of pop, all the while exploring ageless issues regarding self, suffering, and the pursuit of wholeness.