In the social media age, it’s increasingly rare to find an album whose location of origin is imminently obvious. For all the benefits of genre-blending and the unparalleled ease with which we can access music from all over the world, one side effect has been the growing prevalence of music that feels placeless.

Not so for North Carolina’s Fust, whose singular take on alt-country takes inspiration both from Southern rock traditions and the indie-rock associated with the close-by midwest region. On the twangy “Spangled”, which recalls the work of fellow North Carolinian MJ Lenderman, the band litter the song with local references like the torn-down “hospital out on route 11” that give these tunes a rooted, lived-in, diaristic feel.

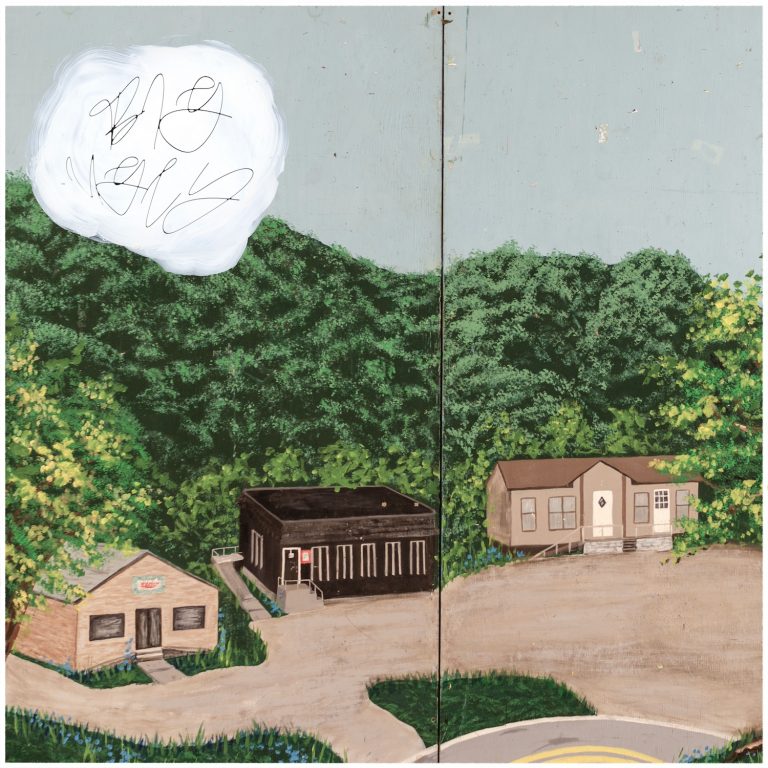

Across 11 tracks, the six-piece Durham band led by Aaron Dowdy, pen a compelling portrait of love, loss, hanging on and the relationship with one’s hometown that only seems to get more complicated as time goes on.

At its core, Big Ugly is an LP about flux states – of relationships creeping towards their end, of familiar places turned haunting, and coping mechanisms that no longer work like they used to. On the aforementioned “Spangled”, old haunts harbour ghosts best forgotten and linger ominously in the narrator’s conscious (“I can’t even visit / The last room I may have been”). While on the standout “Bleached”, the evocative image of holy water “sloshing round down at our feet” speaks to the un-materialised possibility of redemption and salvation. Even when Big Ugly’s characters manage to make a break from the past, they remain haunted by the questions left (“Did they even really like you? / And what did they like about you?”).

Despite examining so many thorny questions pertaining to coming of age and the human condition, Big Ugly doesn’t sound half as heavy as one might expect. The fuzzy, twangy guitars and buoyant drumming provide a cushion for harsh truths, and Dowdy renders his characters in warm, light tones – even when their environment is anything but. “Mountain Language”, for instance, is home to the LP’s most affecting portrait of a time-worn, settled-into intimacy (“We have our own language / Well, I had mine / But yours had all those ways of saying how and why / So we use yours”). Later, “Bleached” uplifts with it’s gorgeous, crescendoing chorus that speaks to the beauty of the mundane (“Were you in the sun? / Did you have fun? / Yeah, you seem lighter”).

The emotional core of Big Ugly arrives via “Sister”, a meditation on grief that finds our narrator “wrecked, wounded [and] wore down”. In the immediate aftermath of loss, mundane objects – moulding bread, a light that’s “still on the brink” – take on new, darkly profound meaning. Listening to Dowdy delivering this litany of the everyday at a mournful, glacial pace, I am reminded of Donna Tartt’s excellent tome The Goldfinch and its descriptions of objects that “wobbled with my fatigue”; haunting in their stillness, remaining stubbornly the same even as grief makes it feel as though nothing could possibly be the same ever again.

The album’s closing triplet – comprising of “Jody”, “Big Ugly” and “Heart Song” – gets down to Big Ugly’s core. The first of the three speaks to the ongoing theme of using heavy drinking to cope (“It’s all we got and it’s easy”) and a relationship whose lifetime has been artificially extended by constantly numbing out. Eventually, however, reality hits with lightning-bolt-like precision, as Dowdy confesses, “I’ll never get enough of what I’ve got”.

On the title track, meanwhile, he sings of accepting one’s enduring connection to their hometown for better or for worse (“I’ve signed my name to the Guyandotte river”) and delivers the LP’s definitive lyric (“I love this town, it shows me my lonesome’s written in the stars”). The mournful, pedal steel-featuring closer “Heart Song” captures the listlessness of modern life in the technology age, simultaneously under- and over-whelming at all times: “There was something I was getting to / It was something I might never do”. Amidst a barrage of existential questioning (“How have I been? / Have I been okay at living?”) and a dysfunctional relationship (“don’t love me for the things i’m missing”), the song (and therefore, the album) ends with a stark admission: “I’m blacking out from living”. It’s a bleak, darkly humorous quip that speaks to Dowdy’s instantly identifiable tone of voice and resists the urge to tie everything up in a neat bow. A fitting end for an album committed to confronting life on life’s terms.