Fay Davis-Jeffers sings and plays keyboard for the experimental and at times rather jazzy trio Pit er Pat, which also features a bassist and drummer. Her vocal delivery is light yet straightforward, not unlike that of Lætitia Sadier or Eleanor Friedberger. The latter comparison is especially apt, given that Pit er Pat toured with the Fiery Furnaces back in 2007. The two bands share both a penchant for the experimental and an unabashed love of hooks; their music is catchy, but this quality belies the complex construction of their songs. There’s more going on beneath the surface of tracks by these bands than you might think based on a first listen.

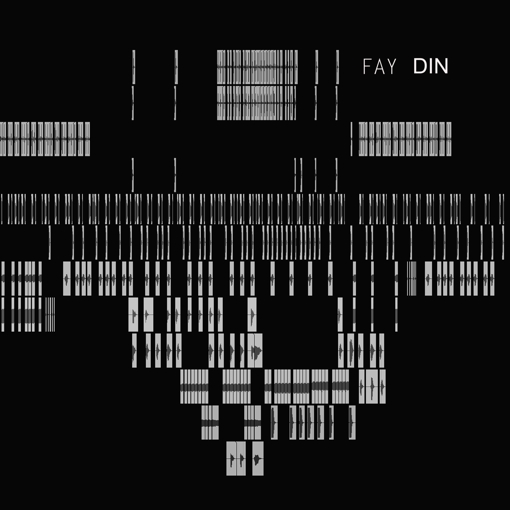

Davis-Jeffers’s solo debut, DIN, is also experimental, but it’s an entirely different beast. Clipped vocal phrases, stuttering percussive samples (heavy on the tablas and bongos), and melodic fragments combine to make a brief LP of uneasy yet foot-tapping electronic minimalism. It’s sort of like a Burial album, only without the urban malaise or nighttime obscureness. What’s great about DIN is the way it alchemizes seemingly dissimilar or incompatible sonic elements into a cohesive whole. For instance, “What’s The Use” seems to build its way from lone vocal yelps and moans and single tabla strikes towards a surprisingly rhythmic climax. But even here, Davis-Jeffers subverts her own formula, allowing the song to explode into a veritable drizzle of drums, Rhodes chords, and guttural vocal emanations that recall collagist tracks like Oneohtrix Point Never’s “Sleep Dealer” from last year’s remarkable Replica album (of which I’m reminded even more upon hearing the breathy vocal samples on “Time To Die”).

Come to think of it, I hear several parallels between that album and DIN. Both build their tracks from bits and pieces of oddly sourced material (challenge: try to count the number of different percussion instruments on “Use”). Both albums employ repetition not as a means of forcing a beat or hook on the listener but rather as a way of letting the disparate track elements to congeal amongst themselves, a very “intelligent design” method of songcraft. That’s not to say both artists didn’t put a lot of work into their LPs–clearly, the opposite is true–but there’s an admirable effortlessness at work here, a playful sidestepping of the pretentious trappings of so much contemporary experimental music.

DIN isn’t all abstraction, however. “Shadow I,” for instance, immediately launches into a woodblock-assisted groove, Davis-Jeffers wringing all sorts of monosyllabic articulations from her vocal samples: “Sha, sha, sha, sha-dowww-dow” is how she repeats the track’s title. Rhodes keys crop up here as well; along with the tablas, they provide an instrumental constant that threads together the album’s otherwise random assortment of sounds. Even when they’re damaged or otherwise toyed with (as on “Between”), they provide a refreshing splash of familiarity within the very alien environment this album inhabits.

Or is it not so random? That’s the beauty of DIN. It’s like a puzzle you’re not meant to solve. With its “tribal” beat and deep synth backing, “Let It Go” could’ve been a “Galang”-era M.I.A. cut were it not for its unsettling vocal harmonies and, you know, fierce resistance to pop structure. That doesn’t stop the metal drum-sounding knocks that appear in the song’s final thirty seconds from seeming like especially sweet chocolate syrup atop the rest of the song’s gooey, delicious sundae. Just because Davis-Jeffers seeks to avoid pop music tropes doesn’t mean her music can’t wiggle its way into your headspace anyway. But isn’t this what pop music sets out to do in the first place? As I said, DIN is an enigmatic affair, happy to entertain but even happier to beguile. It might even trick you into dancing for a track or two, though you probably won’t hear any of these tracks at your local nightclub anytime soon.