Discussing the notion of a musical canon is an incredibly ridiculous venture. For one, there’s the inherent incoherence between the opinions of critics and the informed perspective of other musicians. If you talk to any British musician that was about in 1980, they will very likely tell you that This Heat was all everybody listened to or cared about – yet it took decades for critics to realise the importance the band held, and properly assess the quality of their two incredibly influential albums.

But then there’s also the influence of marketing narratives, often pre-packaged by major label PR officials: ‘hey this album here is especially notable because, idk, we tell you to believe it is!’ Believe me when I say that many music journo-veterans were more keen to believe a press release than first hand accounts of shows or the scene. This leads to a really tampered image, one where it’s harder for the “working bands” that release independently to be recognised, or for their albums to break through in a way they’ve deserved.

FACS exist in this strange twilight. The trio from Chicago used to make up the main body of the post-punk outfit Disappears, Steve Shelley’s group after Sonic Youth split. Then Shelley dropped out due to scheduling issues, and the incredible Noah Leger took over the drums. After 2015’s incredibly abstract and idiosyncratic Irreal, bassist Damon Carruesco exited to focus on other ventures, which led to guitarist Jonathan van Herik switching to bass, and frontman Brian Case to restart the band as FACS.

Shortly after the debut, van Henrik turned to other projects, which had drummer Alianna Kalaba take over his spot on bass for five years. Now, completing the game of musical chairs, van Henrik rejoined, after Kalaba turned to other projects. In their eight years of existence, FACS have managed to release a staggering six albums – each a little different in their sound and body, yet unmistakably their own. My personal standout would be 2020’s incredibly rapturous Void Moments, but it might well be any other record they’ve created.

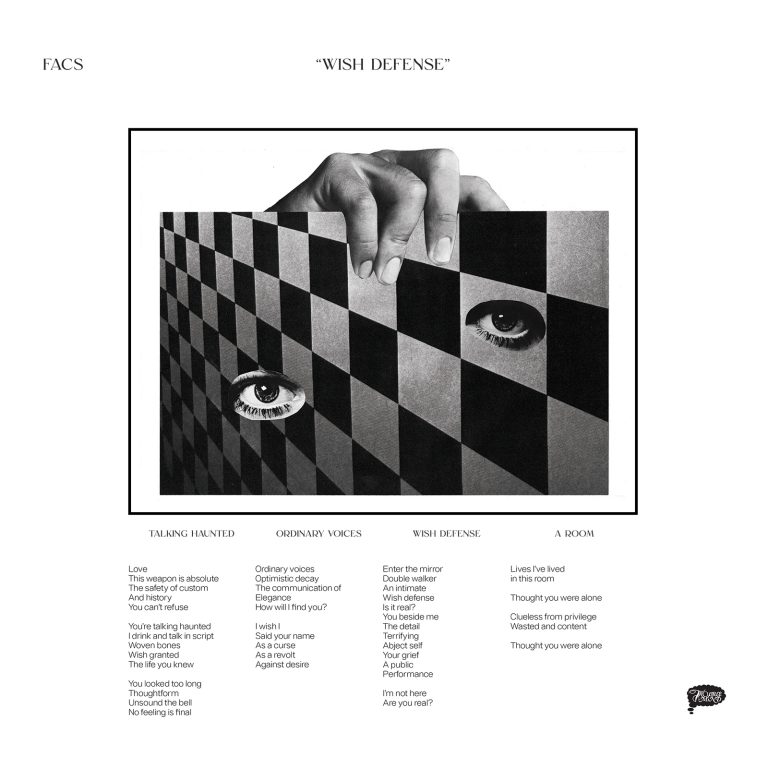

FACS are independent artists in a way more comparable to the 80s and 90s, when later gigantic acts or cult favourites would release with local labels run out of bedrooms, recording and playing shows constantly. It’s a humble and workmanlike ethic, which eludes the glorification of myth-making majors are so dependent upon. Yet their new album, the incredible Wish Defense, unintentionally stumbles into rock mythological significance. After two days of recording in early May of last year at Electrical Audio Studios, almost having completed their parts fully, Case’s phone rang when he brought his kid to school: Steve Albini, their engineer, had suddenly passed away. Yes – Wish Defense is the final album recorded by the legendary Steve Albini.

And what an album it is! Through Albini’s perspective, FACS sound edgier than ever. Where Case often experimented with vocal effects that could lean from echoing sneers to robotic alien voices, Albini forces him into a dry delivery, similar to that of Wire’s Colin Newman. Leger’s drumming is precise and versatile, with a hint of Krautrock groove steering the thundering dynamics typical for an Albini production. Case’s abstract guitar work is mostly stripped of the shoegaze-adjacent layers that characterised earlier FACS albums, instead coming in cutting, sharp and metallic, while van Herik’s melodic bass lines add incredible architecture for Case to form his abstractions around. Even if Albini was not present on the final day of recording and mixing (final overdubs and one vocal had to be recorded with Sanford Parker, while John Congleton took over mixing), Wish Defense is the most charismatic Albini engineered project in a long time.

In terms of material, the album is incredibly strong, boasting a style that seems genuinely post-punk, as opposed to just refashioning a prior sound of that genre-term: it’s exploratory, abstract, authentic, without replicating Gang of Four or Joy Division or XTC to fit into previous mould.

Most of the record is divided between short, anthemic songs that are instantly memorable and feature singalong choruses, such as the title track, the New York sound of “Desire Path” and the closer “You Future”. The others are groovy, melancholic free form explorations of moods – part PiL’s Metal Box, part Glenn Branca. The climactic “Sometimes Only”, with its chiming guitars and ghost-like, echoing overdubs is an exciting example of that, climaxing in an almost transcendental maelstrom of crunching bass over the precise interplay of Case and Leger.

“A Room” goes even further into jazzy interplay, ending up close to the dynamics of Can. Leger’s varied drumming might be the highlight of the track, but Case’s incessantly building guitars are awe inducing as well. Opener “Talking Haunted” flirts with the Goth of Bauhaus and Christian Death, creating a cinematic aura that adds a borderline visual element to the song, creating images for the listener.

In interviews, Case has attributed a lot of the sonic dynamics of the band to their shared interest in films – Cronenberg, Lynch, Carpenter. Images familiar from those directors – of doppelganger, shadow people, identity loss – weave through Case’s lyrics: “You looked too long / Thoughtform / Unsound the bell / No feeling is final”. Mirror forms and the dichotomy of presence/absence reappear in Case’s short bursts of poetry, like nightmare haikus, retaining an inherently political quality. His protagonists seem never quite sure who they are (or what year it is), finding themselves in societal cages they’ve constructed themselves – traps of modern living: “Religious feeling / Domestic but unsafe / Negative / Peace”. “Ordinary Voices” could be one of the best lyrics written this year, reducing struggle to almost occult turmoil: “I wish I / Said your name / As a curse / As a revolt / Against desire”. The song comes closest to the band’s retained interest in shoegaze dynamics, with Case’s psychedelic, cubist playing alternating with massive walls of tremolo crystals.

Not since Ramleh’s The Great Unlearning has a band been this capable in embodying the post-punk ethos. Not since Bowie’s Blackstar has an album been this forceful in finding a spiritual klangkunst. There’s a poetic sense of fate in this. All his life, Albini championed underdogs, working class bands, independent musicians who believed in humility and hard work – people who rarely made a lot of money, instead believing in their art. Here, on his last days, he found himself in the company of the people he sought out, molding their sound to his familiar sensibilities of thundering drums, brittle vocals and metallic, cutting guitars. Speaking on the passing of John Grabski, who recorded with the producer while dying of cancer, Albini once stated: “I hope when I die I go like John, embroiled in the middle of things, surrounded by people I love, doing the things that matter most. I hope I leave a mountain of shit unfinished, that I have a pan on the stove, a phone call waiting and a pencil in my hand. I hope I’m man enough to be thinking about tomorrow.”

Somehow, the album marks the perfect end point for a maverick whose work was marked by transgressive philosophies: Wish Defense is a record about people who find themselves in spaces where time no longer exists. Like the protagonists in the films that influence the band, they observe a world that, slowly, drifts into abstract dream realities, putting existence itself into question: “I’m not here / Are you real?”. But the promise that anything is possible turns on its head – anything could happen to you. Around these ideas, FACS find a sound that is unlike anyone else at the moment, a deeply musical journey into the unconscious. It’s an album that holds power found rarely these days – up there with Joy Division’s Closer in terms of transgressing the boundary between the macabre and ethereal, uniting music to dance to with spiritual experience, marking the twilight divide of utopia and dystopia.