To discuss what impact context has on the reception of music is a frustrating debate. Art can’t be divided from an artist, as it directly correlates with the creator’s identity – conscious and unconscious. But once released, the artwork also exists outside of the artist’s grasp and becomes part of the audience’s own biography and experiences. Even though recent decades have seen quite detailed information about creators revealed, there’s a lot of artists shrouded in mystery or mystique – besides, it seems that most audience members are more keen to consume art than to reflect on its inner machinations. “We need to talk about the artist” thus is a blessing as much as a curse, for some more so than others.

In the case of Ezra Furman, this divide is more present than with many others. Leaving The Harpoons in the early 2010s, Furman released a series of indie pop solo albums which were moderately successful but mostly written off as overtly polite. The Chicago musician was declared a kooky hipster in the same vein of the Brooklyn fashion that came up during the blog-heyday – it didn’t help that there were rather evident parallels to greater, more noteworthy contemporaries in composition and sound, such as Amanda Palmer and Bradford Cox.

But, as her output grew, Furman also developed. Where 2015’s Perpetual Motion People still ran in the vein of Atlas Sound’s obsession with the 50s and 60s, 2018’s Transangelic Exodus leaned more towards a heavy Velvet Underground and Lou Reed palette. Yet Furman couldn’t shake the ‘run of the mill’ taste until 2019’s quite excellent Twelve Nudes reframed her writing into a noisy coat of nocturnal, modernist punk, making this her own private Monomania. Well, it has a little less teeth, but it was a massive step forward for Furman, promising an exciting maturity absent from the previous work, which could mark a bright future.

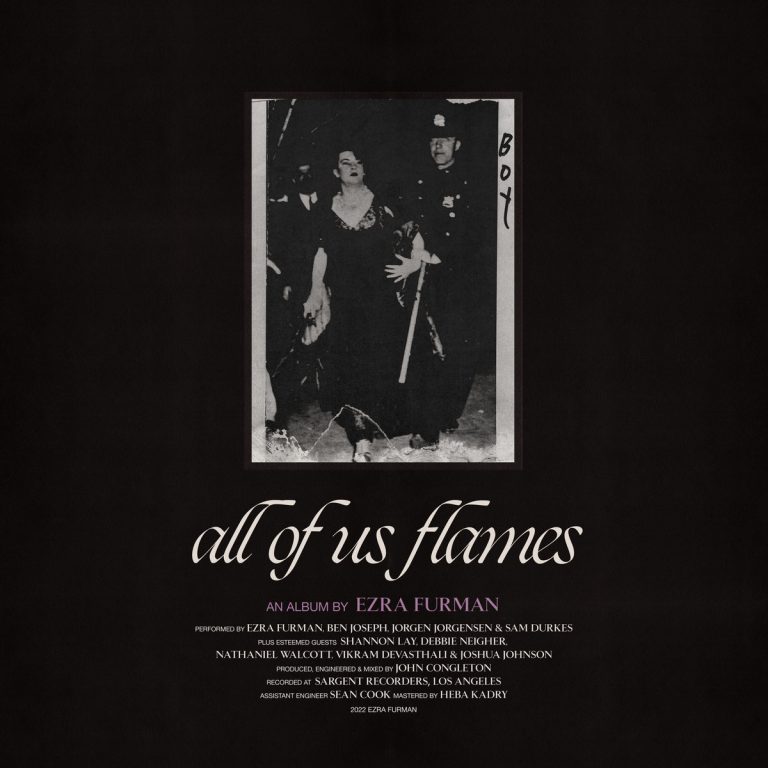

All of Us Flames follows Furman’s greatest career achievement, scoring the show Sex Education, and from the beginning of the album it’s evident the musician has taken a step forward and two back. Inspired by the aura of the great American rock songwriters, it’s rich in references to early Springsteen and the overtly Christian tinged tunes of Bob Dylan’s 80s albums – which means it is also much more formal and adjusted than its predecessor.

Much like St. Vincent’s Daddy’s Home, its ideas of pop classicism as an opportunity to express queer experience are ultimately shrouded in conservative middle of the road radio pop. There’s very little beauty here, and even less that surprises. This means that the exceptions, such as the wonderful John Lennon-tinged “Point me towards the Real”, stand out even more, communicating an urgency of longing which transports itself via its chorus. The prominent drop of “motherfucker” is speculative, but it works because it is embedded within an unassuming structure and recalls the rebellious trickster side of great rock gods keen on provoking moral watchdogs. In other places, Furman uses a disintegrating effect, akin to an old record or decayed tape: the unassuming “Ally Sheedy in the Breakfast Club” is rescued by this.

But these bright spots can’t hide that some of those songs are eerily similar in tone and structure – either to each other, or referencing classics. “Poor Girl A Long Way From Home” recycles Enya’s “Sail Away” in its refrain, while “Dressed in Black” lifts the opening of, well, “Dressed in Black” by The Shangri-Las. It’s hokey in a way where it feels more overt than charming. In general, the formula Furman relies on doesn’t do service to her strengths – the classic Springsteen writing style present in “Forever in Sunset” and “Lilac and Black” feels reined in and part of something else moreso than her own.

And that’s where the gaze turns outward and asks questions related to identity and experience. Furman’s lyrics have often dealt with gender identity and queer sexuality in a stark and unvarnished way, expressing things directly and with naked honesty. However, here she runs into the traps of cliché, reusing images that feel – once more – not just recycled but tired. “I Saw the Truth Undressing” approaches a “pale emperor” image in a way that both leaves little to the imagination but also abandons the power of words, just describing a singular image until it’s fairly worn out. “Book of Our Names” again hones in one single image – that there’s somewhat of an untold history within queer culture – but only finds grey slogans without much colour: “And our names will be heard through prison walls / Through wet city streets and international calls / And we’ll read it until this whole empire falls / And then we will continue to read it”. There’s an air of protest song here, but it just feels anonymous and formless in its prosaic approach. It feels like, in a quest to say everything aloud, Furman forgets that it’s the unsaid, the barely hinted at, that resonates in our hearts. Poetry is a secret language that renders expression beyond the meaning of words.

Thus, all these stories of trains and travels indeed revert back to some of Dylan’s 80s work, but the issue at hand is that quite a bit of that material was already shrouded in tired images which meant more as small chapters of a larger book than individual pages. Dylan wasn’t as lost during that decade as people postulate. He merely sought out new forms of expressions connected with his interest in Christian symbolism, and then tied them to his familiar interest in American folklore. Thus, when Furman does this, she not only imagines what could be billed an unexisting past, but adapts to a modus which her own artistic ventures can’t live up to. It’s all style, without the substance that made this style.

That is also interesting in a more ontological context. It can be observed that a modern canon of music is being built where members of the Trans community work both inside and outside of ‘music business’ constraints, fashioning a musical identity all of their own which consciously plays with history. Adopting pop formulas while simultaneously inverting them, works like Cats Millionaire’s Fun Fun Fun, Patricia Taxxon’s Foley Artist, Cindy Lee’s What’s Tonight to Eternity and Sophie’s Oil of every Pearl’s Un-insides find colourful aural representation of boundaries crashing down and contradictions merging. Meanwhile, artists such as Uboa, Sewerslvt and Backxwash consciously choose confrontation and noise to express pain and express the absurdity of dichotomies. Those albums feel like dreams, and sometimes even nightmares, but they blur all notions of what genre should or has to be, and what it always was. These examples are not meant as direct comparison of those artists with Furman’s music, but it’s somewhat strange how her music stays on the pre-conceived pathways inherent to her influences more so than posing questions to those very heritages.

There is no real tension in All of Us Flames, no burning anger, no heated debate. “Dressed in Black”, which would allow for a direct engagement with the past, even feels like it’s consciously toying with the idea of delusion masquerading as love: “Babe, I know our time will comе, we’ll run away / When we gеt the money saved / We’ll run away into the sun / Stockpile supplies, my knives, your gun / You’ll call my name and I will come”. The feedback might hiss, but it remains in the background, somewhat lacking bite and definitely too polite. Compare this with the soul crushing pain of Xiu Xiu’s “Fast Car” cover, which is also built upon a song of the past but expresses desire and the knowledge of hopelessness in a more muted, yet incredibly touching fashion. The potential Furman only hints at never explodes, never fully forms – it exists always within the very lines painted before her.

What remains is a record that feels all too groomed, all polished execution and often not well thought out. Music to nod and tap your foot along to, then turn it off and move on. Once the train has left the station, there’s not much left behind past the nostalgia of the past Furman hints at. Twelve Nudes showcased the power and talent inherent; we can only long for a brighter future than this present.