We are still afraid of death. It’s the riddle that has occupied humans for as long as we were able to recognise each other. The sudden and absolute silence and lack of what makes us us, and the reflection in observing this moment that we, too, must follow this path, leaves us filled with a suffocating cosmic dread. Most of our actions – subjective and collective – come as a means to evade this inevitable moment, to somehow work against the predetermined fate of ultimate non-existence.

Yet, in reality, death is a process: dying. A slow, creeping entropy that progresses and consumes before it finally combusts in a final embrace. The process makes things harder, as it allows the mind to roam and drift to find spiritual or esoteric comfort that brings with it doubt and delusions of grandeur – those most morbid tend to be those most detached from the reality of each moment given to us.

So maybe art is the ultimate conquest of death: indulging in each moment by creating something that eventually outlasts us and communicates with those in the far future as well as our contemporaries. Maybe that sounds romantic – but art is, in a way, special.

But art, too, can die. For their last few records now, Depeche Mode had become stalled and sounded directionless. Comfortable in their role as cosmopolitan electronic dandies, they spent their time pruning the gardens of their legacy and fashioning tapestries that ended up in the background of their impressive live shows and back catalogue. It could have continued like this for ages, maybe another decade or two, but then Andy Fletcher was just gone. He passed away without warning, the quiet band member that stood in the background and functioned as the glue between the always wrestling Martin Gore and Dave Gahan. And then there were two.

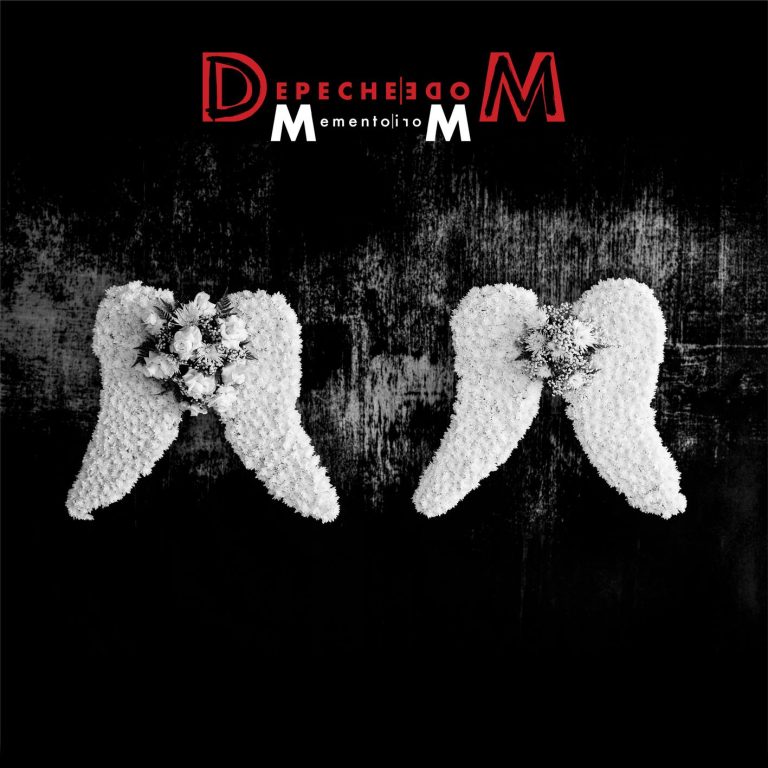

Processing their grief, the duo returned to the studio to expand on the themes that had already occupied their minds during the lockdown: social isolation, the fear of death and alienation from one’s soul. Memento Mori is indeed fittingly titled: it is Depeche Mode’s most self-aware album in a long time – and their most memorable. At 50 minutes and 12 songs, the album is lean and humble, paying respect to the band’s past while also returning to the tension that made their best material so enjoyable.

This announces itself in the opening triplet. “My Cosmos is Mine” is a sinister, thumping waltz that provides a beautiful choral refrain that could have fit on Music for the Masses. “Wagging Tongue” revisits the duo’s love for Kraftwerk (think “Europa Endlos”) but is more assured in its melodic qualities than its siblings on their more recent records, while the single “Ghosts Again” functions as a melancholic new wave hymn in the vein of “Bizarre Love Triangle”.

The mood turns more elegiac on the funeral march of “Don’t Say You Love Me” and the Gore-helmed “Soul With Me”. Both explore emotions of resignation in the face of insurmountable odds, both in and beyond this world, while “My Favourite Stranger” is a perfect example of the nocturnal brutalism the band perfected during their heyday. Rich in grim paranoia, its reworking of Dostoevsky’s The Double almost seems like something natural for the group – something they should have visited decades ago.

The B-side of the album isn’t any weaker. There’s the crystalline “Caroline’s Monkey”, all film noir addiction metaphors and majestic synthesizer instrumentation. It provides Gahan’s voice to explore rich metaphoric imagery for heroin usage, tied up with the haunting refrain “Fading’s better than failing / Falling’s better than feeling / Folding’s better than losing / Fixing’s better than healing”.

Even more personal is “Before We Drown”; possibly a future fan favourite, the song unites Gore and Gahan during the refrain, as they reflect on the empty space left by the absent Andy Fletcher: “I’ve been thinking I can come back home / So how would that be, you and I alone? / All alone? / I have a feeling, you’re not on my side / There’s a distance, between you and I”. The two leads of the group always had a hard time with each other, especially as their respective dependence on alcohol and heroin made collaborations and dialogue contentious. Fletcher functioned as both their therapist and guardian angel, pulling the poles back together. Facing this uncertainty, while also confronting their personal grief, seems to dominate every second of the track, as the instrumental’s rhythm wrestles agains the ambient swathes of the droning keyboards. Emotionally rich and beautifully composed, it’s truly their best in ages.

The majestic “Always You” is equally good. Gifted with the dark aura of Violator‘s leather smell, its tender composition builds into rousing euphoria during its chorus. Hypnotic and sexy, its timeless glow could fit anywhere between Black Celebration to Ultra. The mechanic “People are Good” returns to Kraftwerk’s influence (this time via “Schaufensterpuppen”), while “Never Let Me Go” is a threatening, guitar-driven post-punk attack about romantic obsession. The latter, with its sharp assessment of toxic dynamics, hits especially hard lyrically: “When uncertainty parts / You’ll be ready to concede / It was plain from the start / You’ve been running from me / And I have been patient / I have been so calm / Bit my lips through the torment / Please fall into my arms”. It’s the most confrontational they’ve been in a long time, echoing the archaic obsession of “A Question of Time”.

Where their last few records made it hard to reach the finale in one sitting, by the time “Speak To Me” comes around, it feels like Memento Mori has just started a minute ago. The album’s closer returns to the group’s favoured imagery of religious conquest and spiritual awakening. As the protagonist is lying on the bathroom floor (a familiar image to rock enthusiasts – Elvis), he reaches out to an unknown power, calling for deliverance, as noise mercilessly builds. Yes, Gahan and Gore always wrote about these themes, but as the violins and beats mount to a Wagnerian climax, there’s a sense of importance and poignancy Sounds of the Universe or Spirit lacked. Maybe this newfound urgency came on the heels of realising, in their best friend’s passing, how limited time can be – here today, gone tomorrow. It is indicative how often the two writers refer back to their soul on this record: they face off against a whole new threat now, one which won’t rest and slowly eats away at them. Both survivors, of substances and fame and themselves, they’ll never make it out alive. So why not put up a fight and give it the best they’ve got?