Time slides past us in lines of TV static, becomes pixels, laser beams. Radio echoing in a room seeps into magnet tape before being thrown onto the surface of a silver disc, sent into a white mechanical box, and finally just existing in ether libraries of unbelonging. We lose so much – we lose all things – and cling fervently to memories of archaic ease.

Gender was never a strange subject to me. I grew up observing MTV from across a radiation box, at four and five and six observing Madonna, George Michael, Prince, images of male and female and all things in-between, embodying different personas and wearing make-up, crossdressing and beckoning. The box itself became a conveyor of this strange flirtation, a performance that served to expand the very boundaries of subjects – who cares what you’re wearing? Express yourself!

By the time my numbers hit two figures, grunge and Brit-pop seeped into my periphery – Placebo, Garbage, Smashing Pumpkins, Marilyn Manson all simply lived an experience of being alive as ideas of human beings whose sexuality or gender cannot be conveyed with the same grammar the public spaces seemed to acknowledge. To me, this fact was evident: every human being exists within the ambivalent realm of androgynous self and authoritative opposition, the latter deriving itself from orphanage bureaucracy that applies some sort of ‘value’ to who, what, how we perform the little time we have left to breathe and run wild.

As time marches on, I miss this formative experience of a world that was inherently exciting and inhabited by sprawling individuals that defied the systems they intersected, as opposed to just using them as affirmation machine to dispose capital, the pander-gruel most popstars do nowadays. In the end, everything can be sold and become a sacrifice of Moloch.

Like so many in my generation, I turned to the digital artefacts of reconfiguration to get my fix through worlds of liminal oasis. The warm post-capitalist anonymity of vaporwave, the comforting terror of The Backrooms, worlds reframing the past as aesthetics with all elements of confrontation removed, pure dreamscapes. But then, I never lived a collision of alienation. I don’t identify as part of the queer community, and I do feel quite matter-of-factly confident towards the body I inhabit. What is comforting me (and many others) when I reimagine the past might seem disturbing or oppressive to others, simply because it represents toxic wastelands. This pushes the nostalgic dreams of marginalised people to the outer vicinity, into corners we barely perceive… such as Geocities!

Cindy Lee‘s 2020 album What’s Tonight to Eternity crashed into the lockdown like a meteor, an abrasive noise-pop album that united Xiu Xiu’s flair of melodramatic trauma-collages with the disfiguring neon glow of Deerhunter’s Monomania. The project – which was preceded by a small number of albums and ‘mixtape’-like experimental releases – imagined the drag-persona Cindy Lee as a ghost-like entity. Somewhere between Karen Carpenter and Mary Weiss, Lee’s compositions were haunted by perceived tragedy and harsh bursts of feedback and noise. Like a worn out tape, the record echoed and distorted from an imaginary, somewhat disturbing beyond that can’t be figured – a comfort zone for creator Pat Flegel (formerly of post-punk legends Women).

This usage of drag came with its own pitfalls, as the musician laid out in a Q&A around that album’s release: “I have been perplexed by the novelty in peoples eyes of what I see as a very basic and very traditional performance on my part. This congratulatory/novel ‘outsider’ perspective on what I do is surprising to me.”

Still, during contemporary interviews, the guitarist would point out that much of Cindy Lee’s catalogue came out of collisions with pain and hardship, and seemed faintly dislocated in the present, where Flegel had found comfort and stability – happiness, even. Even then, Flegel would rather talk about Diamond Jubilee, a collection of songs that were much less infected by darkness and were instead ‘weightless’. This collection is now on display, a double album of over two hours, downloadable here.

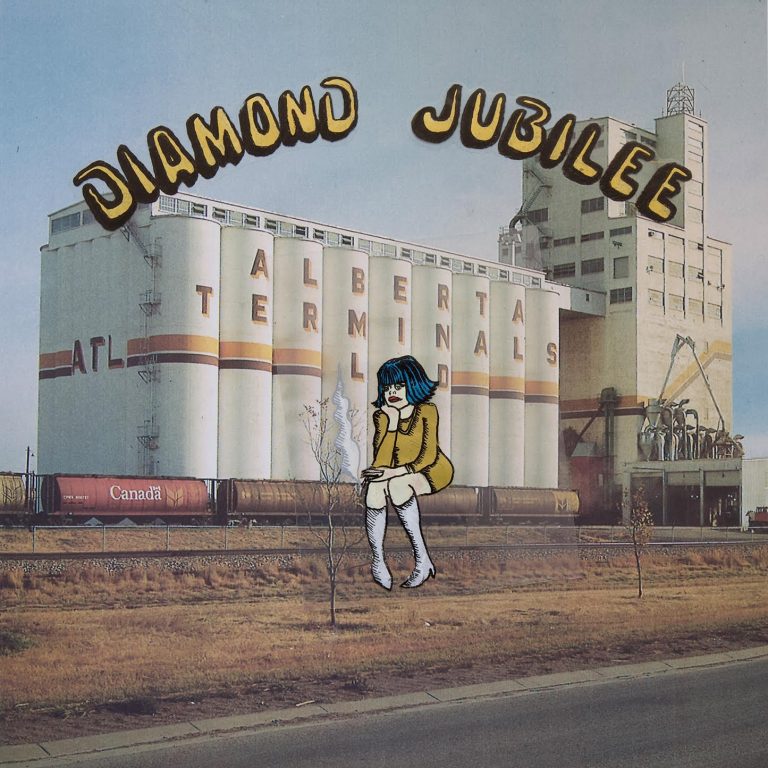

Even though Flegel rejected the narrative of the underdog, it makes perfect sense that Diamond Jubilee exists outside of the music business – it’s not on streaming platforms – only on YouTube or a prehistoric blogsite.

Nevertheless, to call the record spectacular doesn’t do it justice. Over the span of 32 songs, Cindy Lee and Flegel melt into a wholly new sound world of imaginary Americana that feels incredibly hypnagogic. 1966 weighs heavy here, as The Velvet Underground, The Byrds, Ricky Nelson and Joe Meek collide into a strange new sound. Edges are blurred out and voices disembodied. The topics portray the full spectrum of morbid longing and lost love, endless roads and diverged paths. At times, the dedication to atmosphere is reminiscent of Loveless, as the individual songs end suddenly or blur into the next singalong melody. Disentangling the project is time-consuming, so it is best consumed as two distinct discs, as presented by Flegel (for now).

The first half of the project opens with the double punch of the title track and “Glitz”. “Diamond Jubilee” has the cool of a The Velvet Underground & Nico b-side, with its flowing guitar work being accentuated by moody bass and snapped beat, as violins and drums slowly build up. The tension explodes in “Glitz”, a sibling to John Lennon’s “Revolution” that mercilessly marches on with a heavy groove.

The cool balladry of “Baby Blue” recalls Roy Orbison, but already introduces a sort-of self-reflective element in how looping piano and drums are used, similar to the tape experiments The Byrds would engage in. “Dreams Of You” is pure heavenly Brian Wilson vocals and Deerhunter-like punchy rock’n’roll, while “All I Want Is You” somewhat recalls Bobby Vinton’s romantic gestures. “Dallas”’ moody country could fit on an Orville Peck outing, while “Wild One” recalls the warmth of George Harrison’s “Long Long Long” transported to the era of Little Peggy March’s “Wind Up Doll”.

“Flesh and Blood” is a modernist diversion, fit for inclusion in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, while “Le Machiniste Fantome” could be on the soundtrack of early 70s Euro Trash by Jess Franco or Jean Rollin. “Demon Bitch” plays dress-up as John Cale, cozying up to “Lady Godiva’s Operation”, while “Kingdom Come” flirts with John Lennon’s sense of humorous experimentation.

The disc ends with a triple bliss-out: “I Have My Doubts” is an engaging doo-wop piece, “Til Polarity’s End” contrasts dark lyricism of eating disorders and suffering with echoing ambience, shifting the atmosphere to that of a cold crypt. Finally, the instrumental “Realistik Heaven” recalls the tone of Nico’s Chelsea Girl, but a voice is absent.

If the first disc portrays a movement through tragedy into heaven, then the second batch of 16 songs imagines a phantasmagoria of a cemetery party. Considering the artistic progression here, it might well be a document of the death of the hippie dream. Many of the songs here capture the same forlorn attitude that inhabits the works that would portray the end of the 60s, when the Manson murders and violent beat-downs of human rights protestors would shape American pop consciousness.

“Stone Faces” is a sanguine dance track, while “GAYBLEVISION” attempts disco. “Dracula” finds funk not far from Scott Walker’s “The Old Man’s Back Again” and “Lockstepp” toys with the hard rock of Led Zeppelin or Black Sabbath.

Even the ballads hit harder – “Government Cheque” finds the repeated refrain of “Can’t go on living without you”, allowing its guitar melody to fully explore the pain of its protagonist, and “Deepest Blue” reaches the murky, drugged out atmosphere of Exile on Main Street. “To Heal This Wounded Heart” dips into Carpenters territory, thanks to its signature guitar riff, while “Golden Microphone” eerily reflects the perspective of a person in ‘heaven’ who finds themselves adrift in a haunted world. “If You Hear Me Crying” toys with The Doors – fitting, as Flegel’s unprocessed voice often has shades of Jim Morrison – and explodes in a distorted noise-pop intro.

The second disc’s final run of songs loses itself a little, with a few instrumentals that are a little more obtuse than their disc one counterparts and a reliance on crooner ballads that turn down the energy significantly. But this feeling could also be a side product of already having listened to 25 songs that are absolutely excellent in their originality and compositional density, which previously explored the textures that “Wild Rose”, “Crime of Passion” and “Durham City Limit” choose.

Flegel’s performance – both musically and inhabiting Cindy Lee – is strong throughout, and suggests the netherworld early American pop derived its theatric storytelling from. Even if the lyrics do not provide cohesive narratives, they still use familiar tropes on full display which suggest meta-textual interpretations.

Similar to Kenneth Anger’s “Scorpio Rising”, Diamond Jubilee uses the imago of an era to form an aura of Americana, a landscape of rich emotional experiences, which suggests nightmarish qualities in the quest to live the American dream. Cindy Lee’s website is the expression of this dark nocturama: exploring drag, baptisms, tiddy mags, occult imagery and cowboy romanticism, it provides a blueprint of pop cultural links that the mainstream is keen to annihilate.

Where my own (and my generation’s) imago of physicality and spirituality was borne under the influence of subversive channels that drifted into the living room through TV, Flegel suggests that the very fundament of pop culture exists on a shifting spectrum that oscillates between the various uncanny of desire. This marks Cindy Lee as genuinely Warholian in their gestalt: mythologies of death and sex, of dress up and painful honesty, of sucking and sucking, of male and female, of female and male intertwine to form the idea of a past that has never existed as such, yet permeates all of its culture. Its non-existence explains Diamond Jubilee‘s hazy audio and incidental temporality of songs that just end suddenly: like a dream, it’s impossible to carry the phantasm over into the (our) real world.

The record – just like the medium of music – is doomed (or blessed) to exist in this in-between state of ghost-like liminality. Some things exist only through their non-existence, in a brief flash of time, defined through the myths we attribute to them, the outlines we long to perceive within, to imagine another, to feel ourselves.