Most people don’t really seem to get David Lynch. There’s this persistent view that he is this stage-magician type puzzle master – arthouse Riddler, or something – who presents his audience with these bizarre problems they can barely solve. I’ve heard this claim from film academics a couple of times, that Lynch is just creating these obnoxious constructs that “make no sense” for his own enjoyment with no further depth to them.

It’s a very dumb way of reading an artist’s work, honestly. And it totally misconstructs where Lynch is coming from, and I’m speaking both in terms of his autobiography and his artistic interests. A trained painter, Lynch experimented with short avant-garde films as far back as the 60s, resembling the early works of Niki de Saint Phalle, Francis Bacon and Walerian Borowczyk. In other words, it fits seamlessly into the surreal imagery of European modern art that established itself after the second world war – but seen through the American point of view of a Philly school kid.

When Lynch moved into feature film making with Eraserhead, this became merely an extension of those interests. As his films grew in numbers, they explored the aesthetics of Fellini, Godard, Bergman, Bresson and Antonioni, but combined them with the cosmic fear and body horror present in HP Lovecraft’s work. He also explored the iconography inherent to old Hollywood, a place creating suggestive dreamscapes while LA was haunted by violent murders and sexual deviances.

Lynch isn’t just making art for art’s sake, he’s commenting on the very nature and process and history of what he’s doing. Because these processes are so complex, it’s impossible to provide keys that just spell them out. You can’t fully submerge an audience in the genealogy of Lost Highway without explaining the Black Dahlia case and Nyarlathotep and the industrial music landscape of the 90s and Vargtimmen. What you can do, however, is to fully submerge yourself in the works and draw your own conclusions as to what they say about how art and heritage function, how stories are conceived and passed on.

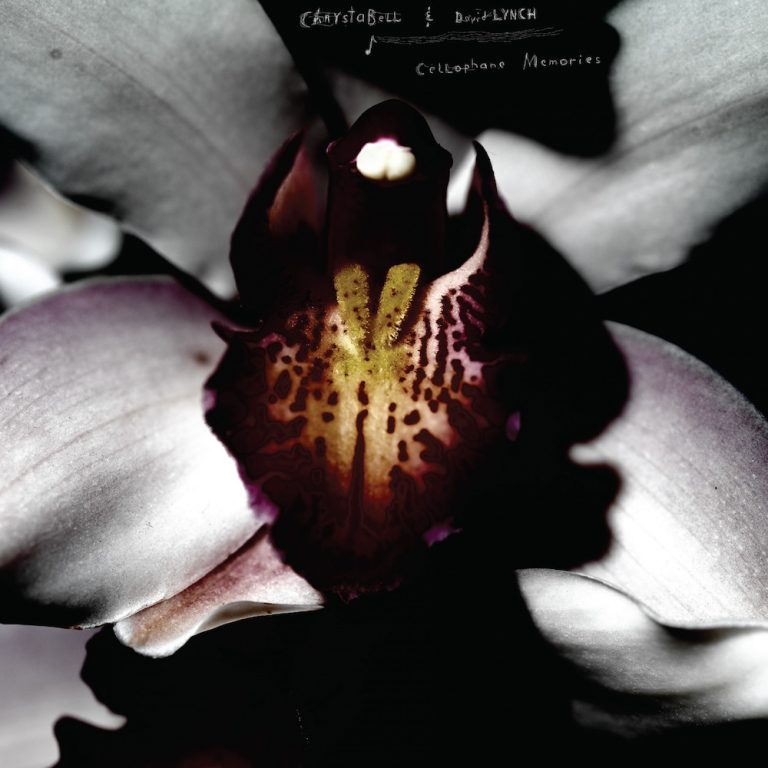

Lynch’s music is an extension of this modus. Cellophane Memories, a collage with longtime collaborator Chrystabell, attempts to explore odd landscapes that are birthed from the genesis of American pop. Elvis Presley’s “Blue Moon” can be seen as progenitor, reaching all the way back to 1956, and there’s obvious ties to Angelo Badalamenti’s haunting synth landscapes. But most of all, the record explores the surreal and icy landscapes French and German synthesizer-led ambient compositions explored in the 70s. Lynch uses Crystabell’s voice like a flashlight in those waving patterns of dark colours, at times fracturing it up, or backmasking it, like an obscure alien incision within his nocturnal sound landscapes.

This allows for incredibly haunting works, such as “Reflections In a Blade”, the brooding and hazy recollection of a violent nightmare that might well be the best song on the album. All drone and ominous sonic charring, it fits perfectly into the sound-world of Twin Peaks‘ third season. The approach also generates great intimacy, as witnessed by “Two Lovers Kiss” and “You know the Rest”, both carried by a single guitar that progresses slowly through a naturally cool composition. Chrystabell’s voice at times feels like a temporal signifier, marking the unraveling of time and inevitability of loss. Everything she expresses becomes, ultimately, a shade of expression more important than the words she sings. It is thrown back at the song, undoing it and leaving little but a ghostly trace.

A song like “So Much Love”, with its naturalist poetry of strolling through forests, poses the question if Lynch is revisiting the past – if he picks up past formulas he explored already, only to enshrine them in personal mythology. But Lynch is less interested in his own past as the unchanging nature of the American landscape and recurrence of those stories. Much of what makes up the lyrics to Cellophane Memories could be set in any century, in any place, recollections of everyday life which could possibly hold a key of some kind, a shard of godliness that ultimately only exists within the confines of short interactions with the outside world.

But Lynch chooses the implicit and unique light as seen in small town streets of the united states, in north-western forests. And the tone of music that he chooses embodies this atmosphere – there’s no other place of reference in “The Answers to the Questions” than an America that recollects its best days but is punished to find only mythology that can never be relived. Brian Eno explored this, often. But Eno found an aesthetic that is almost otherworldly in how emotionally moving it becomes. Lynch seems to aim for this spiritual tone, but strangely enough comes up with more elusive fabric, that won’t suggest moments so much as vague dioramas. The music rarely suggests the impact his lyrical poetry – or Chrystabell’s performance – describes.

Likewise, the protagonists of these songs – almost all women – ultimately reside in an encyclopedia of icons, status and legends. “With Small Animals” describes a strange figure who seeks the wisdom of a hermit, becoming a figure of enlightened beauty that walks with animals and the elements. The harmonica that accompanies the story finds an almost religious awe of this figure, a reflection on beauty which Lynch has often serenaded as impossible, and deeply endangering. It’s possible that in music – which becomes so much less tangible than the image-making of cinema – Lynch allows for an elysian transcendence to exist that the world of reality can’t bear. Maybe where his camera is trapping souls, his music sets them free?

Cellophane Memories isn’t perfect. In its quest for perfumed, nocturnal grace, it often becomes elusive, vaporous even – ghostly. It glides by like a dream, short bursts still hanging on to the inner eye, but impossible to fully grasp. It becomes ambient music, almost exclusively living within the night time, hard to bear or understand when dragged into the cold light of day. There is genius here – how could it not be, given that it is another extension of a unique, generational talent whose art has redefined the world? But there’s also a sense that it is merely a small photo book in the library of larger works, a quasi-religious collection that passes time. Maybe, as held in “Sublime Eternal Love”, it is meant to express Lynch’s reverence of the art of music itself, a love letter to something bigger than him, or us. God is never far away, but neither are the references we find within the material, bringing it back down to earth.

Where Lynch’s films reach beyond his influences, his music is too deeply enshrined in the ambers of popular culture. A solid and polished record, a beautiful collection – not one to outlast time, but to chronicle its passing nature, and the melancholy released from that realisation.