As a child, you typically listen to the music that your parents are playing, be it on their stereos or the radio. At the very least, you do this until you’re old enough to realize there’s other stuff out there, but those formative years will affect your listening habits for life. In a sense, we are all musically indoctrinated, with built-in biases and tastes, and these are often shaped by our families. I come from a musical background; some of my first memories of my little brother are the two of us jamming when the only “instruments” we had were drumsticks, miscellaneous pieces of Tupperware from my mom’s kitchen and a plastic two-octave Yamaha keyboard. Home life = music in the Frank household. It was as much a part of my life as eating.

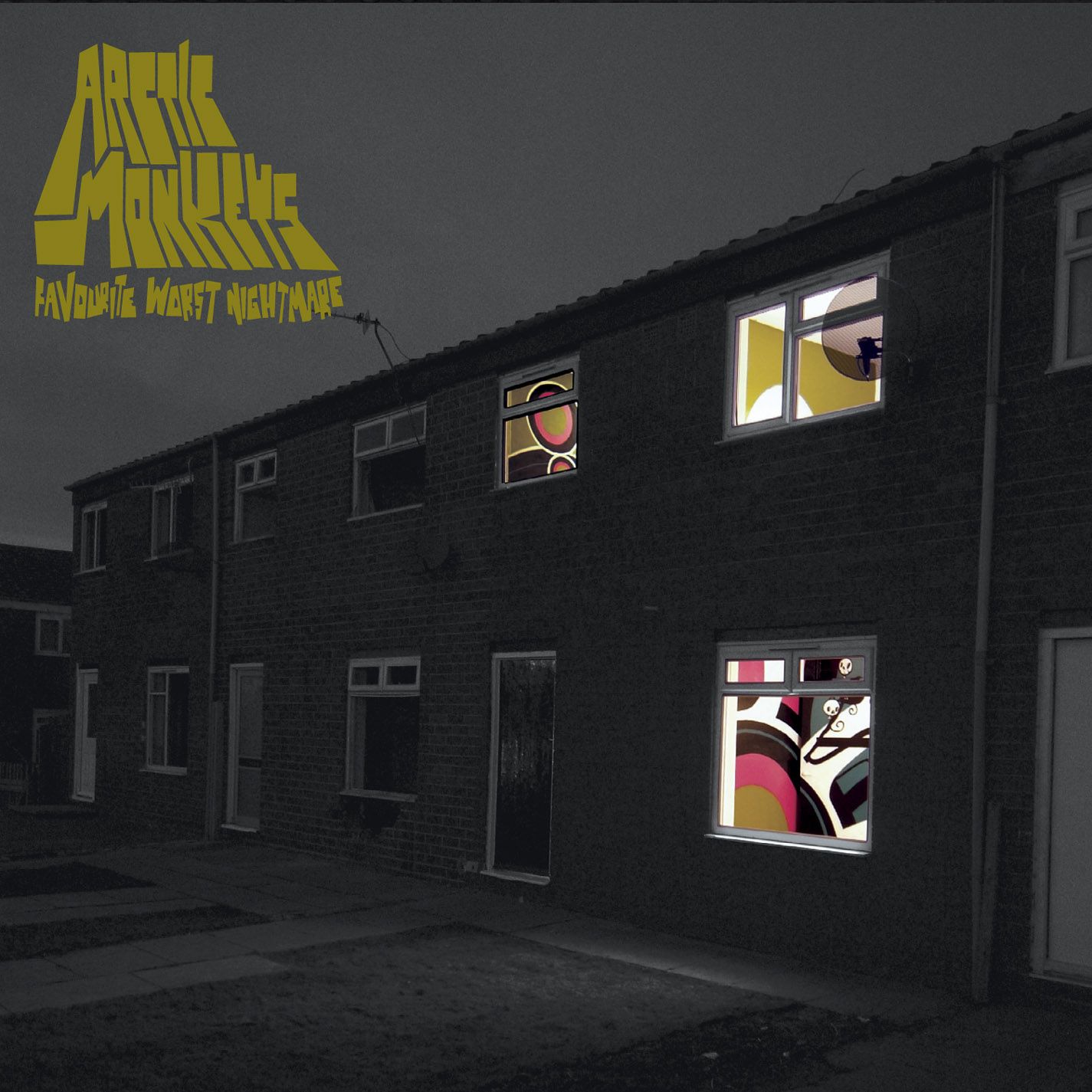

But growing up with that innate adoration, your parents’ music can only satiate you for so long. I hated most of what was on the radio (Strokes and Stripes excluding), and I had yet to really clue in to the communicative power of the internet. I distinctly remember a friend throwing on “Balaclava” in his car in the fall of 2007. To my total surprise, and despite everything my parents had told me, 2001 actually wasn’t the last year that good music was released. Every time I play “Balaclava” the same feeling rushes back like a spring flood. I’d never experienced anything quite like it. Favourite Worst Nightmare was the first record I listened to that truly felt like something I had discovered, something that was mine. It was uncompromised, de-corporatized, breathlessly paced rock music. It hadn’t been played to death on the radio, and my family had never heard of Arctic Monkeys. Check and check.

Every track on Favourite Worst Nightmare kicked and punched like a band that had been slaving away to capture this particular strain of ferocity for years, but Alex Turner, Matt Helders, Nick O’Malley and Jaime Cook were only four years my senior. It also didn’t hurt that Turner’s lyrics were dripping with the sort of sardonic smarminess that every teenager wishes they could conjure in their most sullen moments. At age 17, the less effort you appear to putting in, the better it looks on you, and I couldn’t have been a better stage in my life to fully appreciate the cheekiness of the record’s opening line: “Brian/ Top marks for not tryin’.” “Brianstorm” hit so hard it hurt, almost metal-like in its fury. I am of the opinion that Matt Helders is the best drummer of his generation, and this is still one of the best cases he’s made so far. Every fill, crash and flurry erupts with creativity and confidence, like the world will end if the music slows down (the live version is even faster). The floor tom’s synchronization with the guitars blows me away every time I hear it. Five years on, “Brianstorm” is still the most played song in my music library.

As a musician, there aren’t many pleasure centres in my brain that Favourite Worst Nightmare doesn’t address. It’s a guitarist’s guitar album, stuffed to the rafters with one-off licks, sublime interplay, and bizarre keys and chord progressions. Songs that are superficially simplistic, like “Old Yellow Bricks,” are still incurably catchy and carry a surprising level of depth in other areas.

Favourite Worst Nightmare rarely sounds less than brainstem-grippingly vital. Every note on “Teddy Picker” hits like a gunshot, with teenhood fantasies of fame shattered instantaneously by Turner’s agile vocal work: “The kids all dream of making it/ Whatever that means.” “If You Were There, Beware” metamorphoses flawlessly from slinking insect to thrashing beast, also serving as a glimpse into the sonic territory that the Monkeys would make their own on Humbug. “This House Is A Circus” takes a strobe-lit party and lends it a sense of carnivalesque madness, where the alcohol and whatever else has so far removed you from reality that the house you’re in feels like a maze. From the opening two-note tick to the demented riff it leads up to, you’re in that maze, collecting venomous looks right beside Turner.

Then there’s “505,” arguably the band’s finest moment yet. Turner’s race against time to make it back to a hotel room to meet his lover, with whom he is struggling to keep things afloat, is both invigorating and heartbreaking. It’s flashy, but its subtleties are numerous. Case in point: Helders’ rim shots that emulate the sound of a ticking clock.

Not only is the musicianship here unusually accomplished, the lyrics often read as poetry. Thanks to mainstream radio, I was used to hearing rhyme schemes like “you/true” and “good/would”. Alex Turner rhymed “black hole” with “Tabasco,” “whirlwind” with “girlfriend,” “use me” with “jacuzzi,” and used words like “megadobber” and “soul-pinchers” as if they were a part his regular vocabulary. The closing line on “Do Me A Favour” is still my favourite couplet of his: “How to tear apart the ties that bind?/ Perhaps ‘fuck off’ might be too kind.” It’s tragically, dejectedly brilliant, and it’s something that only he could have written.

Favourite Worst Nightmare is noteworthy as a standalone piece, but it’s even more remarkable because Arctic Monkeys haven’t yet felt the need to make a sequel. Nor is it a sequel itself. If it doesn’t match the hormonal, first-person rantings of Whatever People Say I Am, but it builds upon new strengths: tighter compositions, lyrical breadth, and heightened urgency. They released the fastest-selling debut in British history as teenagers, lost their bassist shortly thereafter, then toured the world, and it still only took Arctic Monkeys fifteen months to top themselves. The weight of these expectations would have crushed most bands, but the Monkeys took it, ran, and ran far. Favourite Worst Nightmare is thoughtful, pugnacious, and totally essential. As a statement on what new school rock and roll can and should be in the age of the blog, it stands very tall indeed.