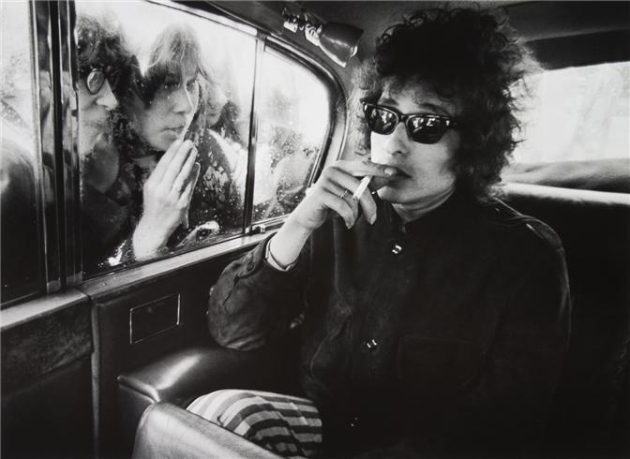

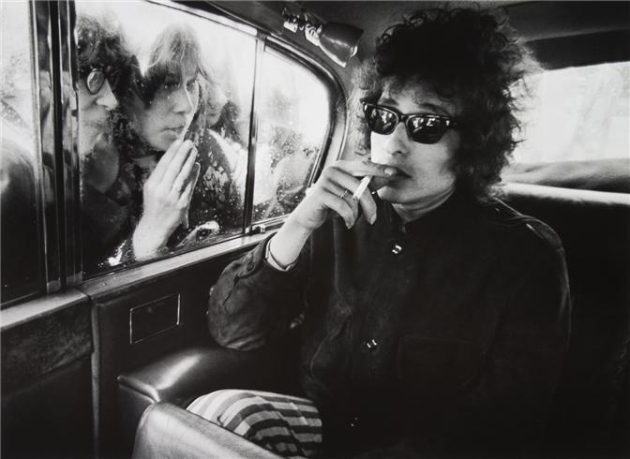

Our Discussions series makes an inevitable stop at one of the all-time seminal songwriters, Bob Dylan.

ANDREW BAILEY: Before we inevitably talk about our favorite albums, I’m curious what your first experiences with Bob Dylan’s music were like. Was it love at first listen or more of an acquired taste?

JACK SPEARING: My whole family hates Bob Dylan. Seriously, all of them, every single one. My brother, although I have a lot to thank him for musically, grouped him together with Lou Reed and Patti Smith in a long and illustrious line of nasal “Eeeuuuhhh” singers. So I was in the rare position of encountering Dylan without any significant experience or prejudice, as I think I can honestly say that I had scarcely heard a single song by the man until I was about seventeen. I seem to remember buying the one album that seemed to be recommended above all others (although I won’t name it yet), during what would become one of my regular spending sprees at the fantastic Fopp store in Cambridge, because I was going through a strange CD-purist phase at the time. And at first, I have to say, I didn’t get it at all. It was annoyingly loud, messy, monotonous, and whiny. The structure of the songs seemed almost brutally simple, and they all went on far too long. Frankly, I felt ripped off. All that hyperbole, everything I’d heard about this guy, and this was all there was? Just a load of long-winded bluesy nonsense? Of course, it had its moments, but I simply could not see what all the fuss was about. But I didn’t give up – I persisted because I was sure there had to be something more to it. It turned out that I’d simply started in the wrong place, and what I was listening to didn’t really make sense out of context. I listened to a few of the other major albums and let them marinate in my mind for a while, and eventually it all fell into place. So yeah, it was definitely an acquired taste for me at first, but ultimately Dylan became one of my favourite musical flavours. How does your experience fit in to this delicious extended metaphor?

ANDREW: Well, the reason I asked is because almost everyone’s first experience with Bob Dylan sounds the same, at least as far as being left underwhelmed. I’ve never talked to anyone who was taken completely aback at first pass.

That said, my experience isn’t any different from yours, really. My parents were always pretty straightforward music listeners growing up. My dad listened to Elvis, Buddy Holly, and Roy Orbison. My mom was into Reba McEntyre and Michael Bolton (seriously). I pretty much hated all this stuff growing up, only because as a kid it’s cool to hate what your parents like. I’ve since grown to love Elvis and Buddy Holly. But that’s sort of besides the point. The point is, Bob Dylan was one of the first “weird” artists I ever stumbled upon. He doesn’t seem so weird now, but when you first hear that godawful voice, it certainly feels that way. I mean, Elvis’ voice is great, but it isn’t challenging. And so the first time I heard him – same as you, I was in my late teens and had been egged on by hyperbole – I didn’t “get it.” It sounded terrible to me, like the most basic folk songs mashed up with a hack of a singer. Obviously my opinions have changed, but those first impressions are among my favorite things about being a Dylan fan.

So then, I have to ask – and I should probably say that I don’t exactly remember what mine was – but what was that first album you listened to?

JACK: Naturally, it was everyone’s favourite Dylan album, Saved. No, of course I’m referring to Highway 61 Revisited. Its heartening to know that most people have the same initial reaction, but at the same time makes me feel like my entire musical experience is one enormous string of clichés. What you say about “weird artists” definitely chimes with me – the fact that he’s so canonical now sometimes makes you forget how distinctive he was and is, even when singing what at first glance seem like “basic folk songs.” I think I really ought to have been better prepared for the voice when I first listened, given that I grew up on an almost exclusive diet of idiosyncratic singers (namely David Byrne and Elvis Costello), and the fact that I progressed straight on to Blood on the Tracks didn’t help, as by that time he’d been through any number of curious vocal personas. The transformations of Dylan’s voice were for me just the first indication of his infamous, and over-analysed, inscrutability, which seems to grow as you learn and listen more, rather than dissipating. Although a considerable amount of mythology has grown up over the years, I think the very lack of information, that the music is left to speak for itself, is part of his abiding appeal. Speaking of which, what is your favourite album? And perhaps more importantly, do you equate “favourite” with “best,” or are they two different things for you?

ANDREW: I define “favorite” and “best” very literally, so to me, they’re different things. One’s subjective, one’s objective, and only one is truly debatable. My favorite – which is ultimately more important than which one is objectively superior – is Highway 61 Revisited as well, though to show just how feeble-minded I was when I first started listening through his stuff, I thought there was a Highway 61 out there and I was listening to some kind of follow-up or re-master. I don’t think it’s controversial to say “Like a Rolling Stone” is one of the greatest songs ever written, and “Tombstone Blues” and “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” are two of my personal favorite songs ever, by anyone. The latter might just be my hands-down favorite Dylan song. Hell, that might be the best three song run to open an album ever, or at least among the very best.

It’s funny though that you mentioned Highway 61 and then jumped right to Blood on the Tracks – at least in your own listening order – because Blood on the Tracks is right there at the top for me too. My personal rankings for his catalog aren’t particularly thrilling; Blonde on Blonde and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, which gets me every time with “Girl From the North Country,” are all on that upper tier. But Dylan’s had a very discernible career arc, at least in my eyes, so it isn’t surprising to see some albums always pointed out and others kind of brushed over (or flat out insulted, like Knocked Out Loaded, for instance). Does that seem like an accurate assessment?

JACK: I like to mantain a facade of mock-arrogance when it comes to music, so for me “favourite” and “best” are one and the same thing. The upshot being that Bringing It All Back Home will always be firmly positioned at the top of my Dylan league-table. I’m not going to try and denigrate Highway 61, because that would be ridiculous, and oddly I probably listen to that album more often, but even now the abrasive anger which permeates it sometimes puts me off. Having said that, the brilliantly articulate bitterness in “Like a Rolling Stone,” and even more so in “Ballad of a Thin Man” are, aside from anything else, some of the most emotionally useful songs he ever produced. I can’t really think of many other songs (especially from that era) which express feelings of alienation and rage with such potency. I can never work out if he’s just decided that he hates everyone, or that everyone hates him. It’s also quite a tuneful album when you think about it, which I think has a lot to do with the unfailingly fantastic support provided by The Band, particularly on “Queen Jane Approximately.” And lyrically, of course, it’s one of the very best, not just of Dylan’s albums, but of all albums, especially on the vast monolith of sound that is “Desolation Row” and the unrelenting agitation of “Tombstone Blues.” In fact, even while I’m writing this, I’m painfully aware of both the inadequacy of my own words to describe his work, and Dylan’s own self-deprecation and constant resistance to praise, particularly by journalists.

But enough of defending the album which isn’t even my favourite – its time for some serious bias. Bringing It All Back Home is the best Dylan album. Firstly, because of the self-conscious stylistic split between the two halves – six concise exercises in the new “electric” mode (I hate to use the word, but there isn’t really another way to describe it), followed by four-and-a-half superlative, breathtaking, rambling journeys back into unaccompanied folk, as though just at the point where he’d perfected one form, he got bored, and tried something different. Every time I hear “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” I can still scarcely belive it exists. No one can be that good a songwriter. Its just not possible. And yet there it is. I can’t remember exactly which track it is, but if you listen to the bootlegs from around that time, Dylan quips at the end of a particularly long number that he’s just about to begin the second verse. I also love the album because there’s a lot more whimsy, ambiguity and well, love in it. It comes from the moment where he’s breaking away from the earnest, politically sanctioned Guthrie imitations of previous years and actually becoming Bob Dylan, but at the same time he’s not so invested in being a curmudgeon that he can’t laugh at himself. It’s not so much the specific songs as the general feeling of the whole set. I think it also shows up how arbitrary talking about “albums” of that period can be – he was writing so many songs that some albums feel like they just assemble the best of his latest output, rather than being specifically conceived with particular governing themes in mind.

I absolutely agree about “Girl From the North Country,” which is the first Dylan song I really loved, and I think it may still be my favourite. It’s difficult and perhaps unecessary to create some sort of musical hierarchy though, because there’s such a huge gulf between the early “plinky-planky-setting-the-bar-for-every-singer-songwriter-since-then” stage and the “LOUD NOISES” stage. And yeah, I think your view is pretty accurate, but I think pretty much every fan has a favourite mediocre Dylan record, or at least one that they like a lot but which falls outside the generally accepted “classic” periods. For me that’s probably Desire, but I think that The Times they are A-Changin’ and Another Side get unfairly dismissed at times. There’s a lot of great writing on them.

ANDREW: I’ve got Bringing It All Back Home pretty high on my list too, although kind of how you say you probably listen to Highway 61 the most even though it isn’t your favorite, I probably listen to Bringing It All Back Home the least of what I would consider my group of favorites. The interesting thing about those two albums, at least in the context of era, is that they’re from the exact same time period. They were released not even six months apart. That’s pretty remarkable to me. I mean, you’re right about the stylistic changes between the two albums, but how many artists could have flip-flopped that quickly and that brilliantly between them? Some songwriters squander entire albums feeling out a new style.

As for his curmudgeon mentality or whatever you want to call it – I actually like that term just because “curmudgeon” is such a great, funny little word – I think that’s one of the things that have always drawn me to Bob Dylan, because I think my personality is probably a lot like his. He’s a guy who has obviously been blessed with intelligence and a caring heart, but he’s also been stuck in this really thick, crusty shell that prevents that from coming out at times. It’s one of those personality circumstances that people can’t fully comprehend unless they’re in those shoes. And I can really relate to that. Along those same lines, I’ve always had this impression that Dylan’s perception of himself has been in some state of perpetual inner turmoil. He’s got to be aware that his talent is sensational, but I think he also has this perfectionist’s spirit; he writes a great song, reads it back, and thinks it’s shit, but we listen to it and marvel. Or at least that’s sort of how I’ve always imagined the mechanics of his brain working.

And I find it funny you reference Desire and The Times They are A-Changin’ as mediocre records. I mean, obviously you framed it within the context of his own catalog, but how ridiculous is that? Songs like “Hurricane” and “Isis” would be apex moments for so many other songwriters, but for Dylan we just sort of breeze right over them. I mean, even an album like Modern Times, which I think most critics were a little biased in hailing, is full of some really fantastic writing. Yet we just sort of catalog that away in this “modern era Dylan” file.

JACK: Absolutely. I think Dylan’s main problem is the fact that he has to compete with himself, with his own body of work, his reputation and people’s appraisals of it.

At the risk of making too many cross-cultural analogies in these discussions, those two albums coming one after another in such a short space of time reminds me of how someone like Ingmar Bergman could knock out two cinematic masterpieces (The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries) in the course of a single year. It takes a special kind of genius (yes, I’m using that word) to churn out work like that and make it look not only easy, but graceful. I like that we get to see the gradual transition, as opposed to someone like Bowie who makes very abrupt changes in style and persona. The same goes for the way the Rolling Thunder Revue-era Dylan sprawls across both Blood on the Tracks and Desire.

I imagine you’re probably right about his personality, and I think quite a lot of people, particularly “angry young men” can relate to it. Its a pretty incredible trick to pull off when you think about it, managing to be so intensely specific and yet having this incredible universality. Who hasn’t had a moment of disillusionment that fits with “Positively 4th Street” or an infatuation which would be adequately soundtracked by “I Want You”? You feel it especially in the live recordings, the transition from New York in 1964 – fresh faced, almost naive, joking with the audience – to London in 1966 – the oft-quoted “Judas” incident, general hostility – and then another transformation in the 70s – older, wiser Dylan, dealing with pain and experience. There’s another arc going on, and its a deeply personal one, even if it is veiled or evaded outright by Dylan himself. I used to be intrigued by his contradictory claims about the meaning or content of the music, but now I think a lot of it was just disingenuousness, largely to irritate to the press, so I think its best to just fill in the blanks yourself. As ever, the man himself expresses it best.

And yes, I agree, there is something silly in talking about mediocrity – it’s like when Mozart or someone writes a half-baked piece, it’s still infinitely superior to what most people are doing at the time. That’s the trouble with people who are so obscenely talented. Blood on the Tracks in particular shows up the problem with that kind of thinking – it lets truly great songwriting go neglected because of the assumption that the “classic” period is over. We’ve touched on it a little already, but what do you think about that album?

ANDREW: I adore Blood on the Tracks. I remember when I was first struggling to get into Dylan’s music, I regularly posted on this sort of all-topics forum a lot – it was a great way to make time go by faster at work. Anyway, I started seeking out suggestions for what to listen to because I wasn’t “getting it.” The suggestion I got over and over again was “Tangled Up in Blue,” which I listened to and was okay with, but didn’t fully grasp until I sat down and read the lyrics. Being introduced to that song early on sort of led me into exploring the whole album very naturally.

“Idiot Wind” remains one of my favorite songs and I’ve always had a fondness for “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.” He doesn’t really write “hooks” the way we normally think of them in popular music, but I think that song has one of the catchiest hooks of his own kind. “If You See Her, Say Hello” is obviously another brilliant one (and Jeff Buckley’s Live at Sin-é cover is phenomenal, too). That song has always felt very comforting to me, the way he acknowledges this very natural, common thing people do after relationships where they completely cut ties and go off in opposite directions and then, at the end of the song, very tastefully approaches the other thing people sometimes do, which is come together years later as smarter, completely different people. Actually, I don’t think I can pick a stone-cold favorite song from this album, can you?

The other thing that’s kind of funny to think of – especially for you and I, since we weren’t even alive at the time – is that Blood on the Tracks is historically what put Bob Dylan back on the map, at least in popular and critical opinion. He’d been on something of a dry spell, or at least a dry spell by his own standards, for a while there, and so Blood on the Tracks was really a return to form.

JACK: I can never quite get over the sheer songwriting craft that went into something like “Tangled Up in Blue” – if you aren’t listening properly you miss everything. To carry on for six minutes without a word out of place, without an awkward rhyme, despite talking again about incredibly specific events with all these evocative images – poetry books, shoelaces and so on… It’s just astounding. It’s even more impressive when you hear different drafts and versions of the songs on Blood on the Tracks and realise how they were in a near-constant state of lyrical flux. Some people have Blood pegged as a depressing album, but as with any music where people make that comment, I always just think that it’s only as depressing as you make it – if you don’t linger too much on the heartbreak and emotional wreckage and just stand back and admire it from a distance, it’s still devastating, but cathartic and beautiful at the same time. There’s a really strong narrative thread that seems to run through that album too – you feel the passage of time rather than being held in stasis in a particular mood or situation. I have a lot of time for the songs you mentioned too, particularly “Lily” because it’s one of those classic “I’ll just add another verse…” songs along with “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” and “Desolation Row,” and again it’s so evocative – you see everything from the silver cane to the gallows. I also really love “Shelter From the Storm” as well though – it’s like a well-written country song, not stylistically, but because it has this lyrical inevitability – you feel every verse building inexorably towards that same title line. Maybe more than any other Dylan album, that one has been subject to far too much interpretation – do you like to read in your own meanings to his songs or try to decipher them to get to the “truth”?

ANDREW: As a general rule, I like to try and find my own meaning in songs before trying to figure out what they were intended to mean. The same goes for Dylan, which is usually pretty easy to do because, as you said, his words are so evocative. When he’s writing about personal experiences, even though he’s very specific, he isn’t so specific as to alienate his audience. I mean, even those songs where he references extremely pinpointed events – “Sara” comes to mind – he still is able to make an emotional connection. I think that’s a key. But I do like going back after I’ve applied the song in my own context and then figure out what he meant. Maybe not for every single song, mind you, but certainly the ones that hit me the hardest.

So, at this point we’ve pretty much established that he’s a songwriting god. Of course, he didn’t really need our co-sign for that. Anyway, I’ve long since had this bucket list of artists I need to see live. I’ve still got Waits, McCartney, Neil Young, Kanye West (one of these things is not like the other) on that list. Last year, I believe it was, I had the opportunity to cross Dylan’s name off – emphatically. I saw him play with his band in this little college arena down in Washington, DC and was floored by just how painful it was to sit through. Now, I’d had tempered expectations to begin with. He’s a notorious hit or miss live act, though most fans would say that’s totally contingent on his mood and effort. In this particular show, he seemed fine. He seemed like he was really trying to put on a good show. But man, it was terrible.

His band seem like talented enough guys, but the arrangements were brutally generic. He’s also rewritten many of the arrangements for his songs, which on some level makes sense – how would you like to perform “Like a Rolling Stone” practically non-stop for 40+ years? But, at the same time, it’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” Why on Earth is it being messed with? Because of this, many of the songs were totally unrecognizable, his voice has clearly been tattered through the years, and the good parts of the show were, like I said, so easily interchangeable that they just didn’t offer much. I was disappointed, but at least I’d crossed his name off my list, you know? Anyway, coming out of the arena, I couldn’t help but overhear people go on and on about how fantastic the show was. People were gushing. It was completely baffling to me. I mean, yeah, it was “The Legend,” but where’s the objectivity? Have you ever noticed this type of thing with Dylan, where people just sort of give him the benefit of the doubt even when, all things being equal, he doesn’t really deserve it?

JACK: Even heroes have feet of clay. If I have noticed it, it hasn’t bothered me too much. I’ve never been particularly keen on the idea of going to see an ageing rocker live, and I think when it’s someone as notoriously indifferent towards his audience and band-members as Dylan, you have to expect a certain amount of deviation from the “originals.” I think what you point out is symptomatic of a lot of artists, not just Dylan, but a whole generation who are now somehow above critique because their oldest fans have so much invested in them.

A couple of years ago I really enjoyed hearing Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, where he would dig up utterly obscure numbers and place them alongside established classics – the whole thing is pleasantly whimsical and leads you into all kinds of neglected musical areas you’d never otherwise encounter. I mention it because I like that Dylan is (although it’s been pointed out a million times before) constantly restless, never satisfied, always looking to diversify his legacy. The radio show makes you aware of how his voice has, shall we say, gained character, but I think he makes the best of it, as Leonard Cohen has been doing recently too. So maybe he can’t reach all the notes he used to be able to sing, and maybe as Joan Baez has said, he changes things just to fuck you up – but after all, folk music (even if the man himself would object to the term) is all about things being passed on, reinterpreted, rearranged. The content of the song is almost irrelevant, what counts is the oral tradition behind them, stretching off into the distance.

ANDREW: I loved his foray into radio! I’m really drawn to what musicians I love are listening to. There’s this big family tree of influences that I’ve always found very useful in discovering new music, and those broadcasts were extensions of that.

JACK: And as a final controversial statement to aid further discussion, I’d like to say that Blonde on Blonde is a bloated mess that could happily lose half of its songs.

ANDREW: Um… okay. That’s not controversial. That’s blasphemous. I mean… half? Half?! That’s insanity.

JACK: Yeah I don’t really think that… but some are definitely a lot stronger than others…

ANDREW: Whew. I was worried there for a second.

Other Discussions:

Tom Waits

The Velvet Underground

Led Zeppelin

Sigur Rós

Pavement

Radiohead