Throughout his career, billy woods‘ writing has circled around abandoned and liminal spaces. Hiding Places imagined haunted houses as America’s subconsciousness, Aethiopes ventured out into space to judge earthlings and Church had memories and dreams melt into a thick fume. woods himself projects this diffusion onto his own face, which he distorts, blurs and covers in many ways on promo-pictures; the direct embodiment of a nation that cannibalizes itself. Many read the long-term New York resident as the apocalypse-preacher of this generation, but it was just a question of time until the fog would clear to reveal the man behind the myth. Yet there’s only so many ways for a magician to let go of the comfort of darkness without revealing his tricks.

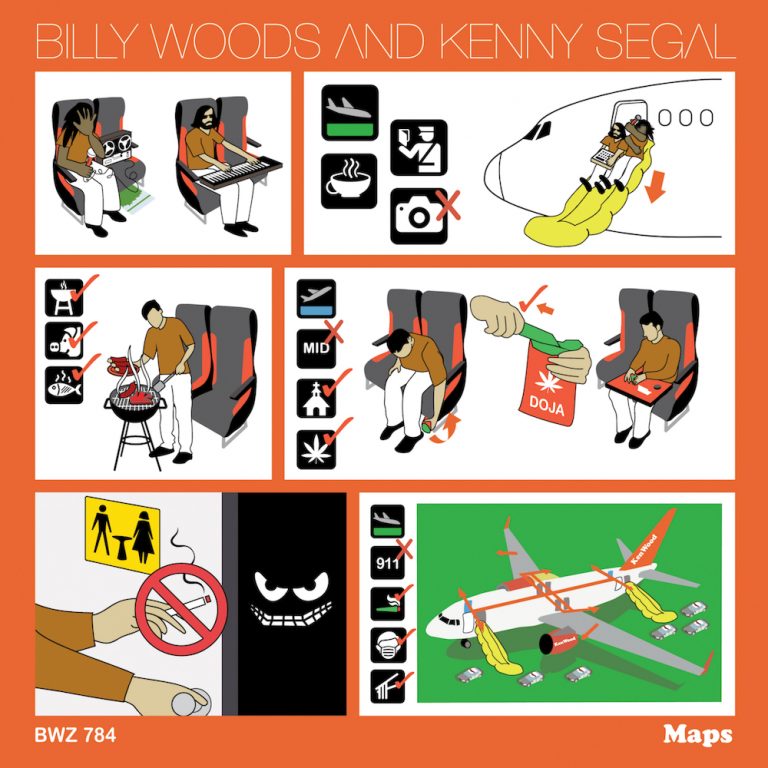

It makes absolute sense that woods would approach airports, empty venues and packed planes as the compass for Maps, his second venture with producer Kenny Segal (following the aforementioned Hiding Places). All of them are transitory or incidental spaces, in which individuals remain anonymous while out in the open for all to see. Conversations started here lead nowhere, destined to fill the empty minutes that tick down to the next phase of transition and strangers remain just that. Years later and the faces blur, with only faint memories of moments surviving. There’s a metaphor for the journey of life here, how unbound systems and time force us always forward, while consumption of goods, food and drink suggests the illusion of normalcy, all while we find ourselves under the eye of surveillance, tracked, sorted, processed, dehumanized, forgotten.

It would make sense if billy woods had found metaphors for our division within these settings’ dark labyrinths, but instead he observes his travels as vacation of the dread that permeates his home town and poetry. This is best observed via the record’s two bookends, which functionally document the decline of NYC as cultural habitat.

“Kenwood Speakers” chronicles Brooklyn slowly selling out. woods observes he can afford more exceptional real estate thanks to his artistic longevity with bitter utilitarianism; “Bed Stuy, got one eye on them guys / The other on a crumbling mansion / If it’s gon’ get gentrified, I’m not trying to leave it empty handed”. Later, during dinner with his new Brooklyn neighbour, filled with suggestions of hip and decadent white status symbols (“Skate wing, brown butter and capers / Sprigs of thyme / Heavy pours of natural wine”), woods supposedly provokes the man into ruminating on class and racial division (“I turn the music up incrementally and told mischievous lies / I whispered in the host’s ears all night”). The next morning, he’s found dead of suicide by carbon monoxide.

While the song’s sudden shock ending marks the start of woods’ journey around the world, the imagery of a gentrified Brooklyn returns later with “NYC tapwater”. Here, woods observes celebrities moving in next door (suggesting the place of his deceased neighbour found ample interest) and luxury goods being traded, which the rapper takes with resigned sarcasm: “Where I used to cop at, now it’s a Blue & Cream (I see you Jeff) / Four hundred dollar Japanese jeans (They’re actually very comfortable) / Meanwhile, my bodega akh selling weed (No thanks, man)”. As he watches fumbling crabs in a bucket, he returns to the suicide on the opening track: “Survivor’s guilt with a side of buyer’s remorse / I’m home, but my mind be wandering off”. The death of New York as cultural habitat directly contrasts the sprawling, almost alchemical processes of the diary-like observations on the rest of the record.

“Kenwood Speakers” cuts out immediately, but it’s not an admission of guilt so much as a palette cleanser. Only a year ago, on “Smith + Cross”, woods encapsulated Black identity with the lines “Sugar, molasses, rum / Sun blasted bastard’s son”. To him, what we eat – thus consume – is as much part of a cultural lineage as is the colour of our skin. And as the variety of dishes on Maps continues to pile up, it becomes more notable that the quality and density of food is meant to communicate the image a host wants to project – signifying changes in class dynamics or racial experiences – which contrasts the experience of the traveling rapper who is catered with whatever promoters and labels see fit based on their judgement of his quality as an artist. As Elucid puts it on his guest spot on album closer “As the Crow Flies”: “Everybody cooking, I’m just cleaning in my kitchen”. So, instead of returning to similar images as on Aethiopes, follow up track “Soft Landing” opens with sun-drenched guitar chords and field recordings of a public space. “Excuse me”, asks woods, “on those drinks?”

As he’s ruminating on the album-opening suicide with a quote by Josef Stalin over a couple of daiquiris (“A single death is a tragedy, but eggs make omelets / Statistics how he look at war casualties”), woods finds himself at odds with the mother of his child and ruminates via Toni Morrison’s Beloved. In the book, the lead character is an escaped slave haunted by the ghost of her daughter, whom she murdered to evade detection from her former ‘masters’. As usual with woods, this becomes the springboard for a myriad of thoughts, which in turn encapsulate the many returning themes on Maps. These include: society’s classification of food as cultural class signifier (“Conch fritters crispin’ in the kitchen / Grew gaunt in prison”), romantic relationships as an entrapping cage (“My own warden, celly, and superintendent / Flaunt flagrant disassociation”), the hypocritical idea of a free nation that arrests black political dissidents (“We got lists of names, pages and pages / Wouldn’t want to waste the space the previous regime gave us”) and suicide as a form of miserablism that is dwarved by global tragedies (“Maybe Suicidal Thoughts was the Everyday Struggle / […] From up here the lakes is puddles”). Even while drunk on an airplane, roaming the sky like a bird, he finds himself in the throes of a society that sees him – and any black man – as second class citizen, while also taking shots (literally) at his partner: “When the contract came, white man read while I sit, brow furrowed / Rappers leant out Second Amendment with the beam / It worked for William Burroughs”. The song ends with woods texting an Ex, but omitting the actual message as the pilot announces the landing in Amsterdam.

From here, Maps progresses forward in a straight line; it’s both tour diary and note-pad of sensory thrills. Almost every song includes a different type of dish, cross-referencing the aura of the places wherever the journey led – there’s In’n’Out burgers, gazpacho and deep fried pork belly with fresh mint, thai basil, pickled watermelon rind and julienned scallions. It seems superfluous to note, and antithetical to the philosophical point these dishes make, but a cookbook based on the record would be a smash success.

Weed is a constant companion, filling airport toilets and Marriott hotel bathrooms, the papaya or herbal smell of its dissipating smoke a great metaphysical symbol for woods’ transitory presence in those spots. The constant back and forth between black working class rusticity and contemporary white folly collides in occasional power-struggles, such as in “Blue Smoke”, where woods imagines possible FBI agents that listen in on his divorce quarrels self-censoring their racist speech (“Been on this n-word for months, I think it’s all just rhymes”). Even more poignant is the collapsing of those lines in the sinister “Babylon by Bus” where, set to a garishly slowed-down sample of Aphex Twin’s “#2” that drifts into orchestral swells, woods imagines himself as an ominous stalker: “Lake Michigan a frozen pond / Black swan with the bubble butt / Opera glasses clutched front my ugly mug / I administer the food and drugs”. The lines could both be a callback to the pigeon-poisoning old ladies from “Remorseless” or something much more sinister in relation to his separation – things are too diffuse to tell.

woods perfectly encapsulates this modus of cryptic poetry with the opening line to “Blue Smoke”: “Over time, symbols eclipse the things they symbolize”. The experience of these travels – through places, restaurants, venues, weed strains and bathrooms – ultimately leads to a new form of modern man, a character that is outside of class confines, yet still chained to his cultural heritage and riddled by anxiety: in “Bad Dreams Are Only Dreams” (the title is one of the many easter-egg references to 90s Hip-Hop, in this case GZA’s “Cold World”), woods dozes off on an Emirates flight and finds himself the exposed-brain-dish in a Hannibal Lecter-like nightmare that doubles as a parody of critical analysis (this reviewer is very conscious of his own role in this gory folly – thanks for the gruesome shout out, billy! Consider this review the chilli oil pickling from “The Layover”).

If one follows the analogy of last year’s dual releases as his Kid A and Amnesiac, then this new album marks the rapper’s own In Rainbows. To most curious listeners, Maps will seem like a lighter, breezier version of the doom and gloom woods is known for. But all the sunny, Californian jazz-beats Segal conjures, domestic bliss of the beautiful “NYC tapwater” (“Sometimes I don’t tell anyone I’m back around / Just lay low, crack a fresh pound / The cat miss me the most, purring loud on my lap / Tranquilo, fragrant smoke lazy in the air”) and rural fantasy of weed-dealer-cum-farmer in “Agriculture” (“Same greens cooking with a hock / I grew them in the shade / Used to plot on the come-up, plot on my brothers / Now I get the tomatoes cropping sideways”) hides an encroaching darkness – or as woods puts it: “I say I’m at peace but it’s still that same dread”. Which, naturally, is where Aphex Twin and the opera glasses seep in: white culture permeating blackness, transforming it, reflecting itself, leading to a dynamic of self-annihilation.

That leads to the Danny Brown collaboration “Year Zero” (a possible Nine Inch Nails reference?), where both rappers imagine a wasteland of black self-destruction and human devolution: “I quit lookin’ for solutions (no offense) / Bought a pistol and learned how to use it / You can’t fix stupid / Apes stood and walked into the future / March of progress end hunchbacked in front the computer,” woods raps. This black pessimism also seeps out of the morbid “Hangman”: “I’ma keep it real with you, it’s the things you can’t undo / The past, the black Rubik’s cube / A time-lapse, running in place like old cartoons / […] Paper and pencil, I wrote the verse like hangman / No need to ask who sent you, it was always just a question of when / An ill wind in the trees, saplings bend / That bird in the hand squeezed dead”.

The usage of birds in poetry usually signifies an image of boundlessness and emancipation – in the context of black liberation notably to be found in The Beatles’ “Blackbird”. The parallel is more physical with woods, embodied by the returning image of him as an airplane passenger, but the birds remain ambiguous throughout, often becoming a transfiguration for his faltering relationship, which he addresses without varnish in “FaceTime”. As his couples therapy zoom meeting gets declined, the evening redness of the west mirrors woods’ negroni, tinging the images of a faltering love in its sunset blood red. Where, earlier in the record, he stalked the black swan with poisoned food and crushed a bird to death in his hand, on “The Layover” he sees “Magpies pluck jewels out my tombs” and with the final track the crow doubles as a familiar. There’s a constant sense of doom that accompanies the man, a grim sense that he might be on a list, somewhere, somehow. Likewise to the birds, the cat in “NYC tapwater”, which purrs in his lap, strays around town and is afraid of rats, might not ‘just’ be a cat.

As woods returns home and settles in, he finds himself observing his son playground fighting on “As the Crow Flies”: “He been climbing higher and higher on the jungle gym / Running faster, sometimes pushing other kids / Tear streaked apologies, balled fists, it’s a trip / That this is something we did”. Here, in those final lines, he has all the themes of Maps fall in on each other: the romantic tension dissipates, as his own fear on death, embodied by the suicide that opens the album, finally becomes palpable: “I kiss her on the lips / I watch him grow, wondering how long I got to live”.

With all its richness, nuance and double entendre, its cultural observations on food, its constant pleasant weed smell, its soft jazzy beats, its political concerns on black self-sabotage and sexy metaphors, it’s hard to argue that Maps isn’t billy woods’ strongest album to date. So I won’t: woods has transcended the line of being a great artist and entered the realm of genius. With Kenny Segal’s help, he has conjured a work that is wholly its own, both in the artist’s discography and in the rap genre. It’s always a little hokey to compare contrasting artists, but let’s play a quick game of parallels: if Kendrick is our Bob Dylan (a political activist and poetic genius), Denzel our David Bowie (a colourful chameleon and stylistic virtuoso) and Earl our Syd Barrett (a metaphysical hermit and master of dissonance), then billy woods is our John Lennon: a fierce observer, both jester and soothsayer. A visionary like him is one of a kind. Let’s celebrate him while the crow’s still flying high, before the airports empty out and we are only left with shadows.