Let’s unpack the term ‘lullaby’ for a sec. It’s an act of song used solely to soothe a person into rest or slumber. Lullabies are meant to be sung in a confidential caring space, away from prying eyes, contrary to the widescreen pop song, which is music that usually functions as a great connector for a mass audience.

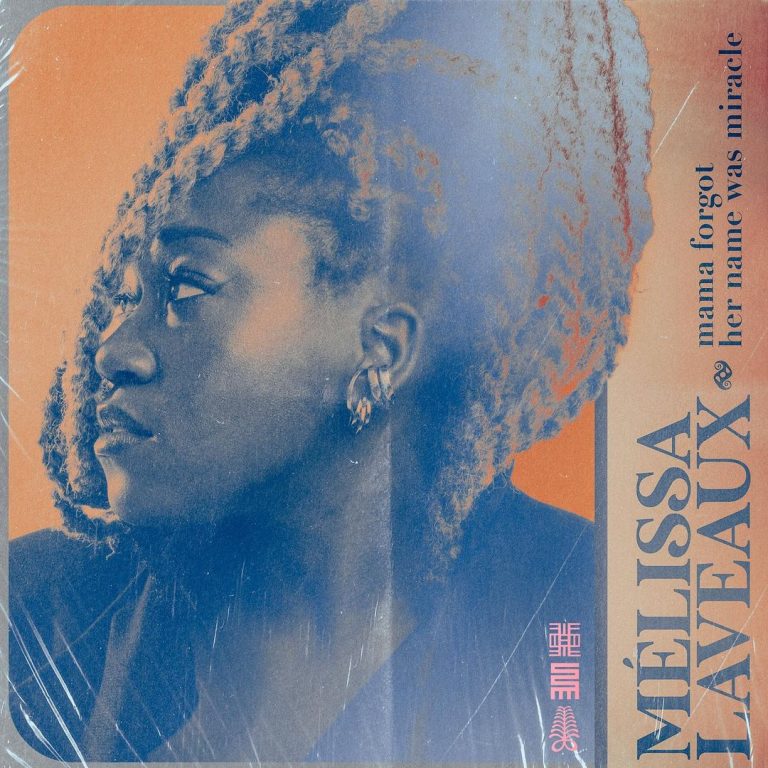

Mélissa Laveaux’s new album Mama forgot her name was Miracle explores these seemingly disparate musical directives in a bold, celebratory way. The Canadian-Haitian, Paris-based artist and musician was already treading this path on her previous LP Radyo Siwèl, reinterpreting bygone folk spirituals within a modern frame of reference.

It was a pivotal record from several angles: it partly reclaimed Laveaux’s own cultural displacement through myth and forgotten history, along with her musical project Sometimes the Flower is just another Knife. One song, “Lasirèn La Balèn”, chronicles a girl escaping a slave ship, drowning herself to become an immortal spirit passing from one body to the next across several generations. It’s kind of a shrewd meta-ploy: because the song also shows how myths are being passed on throughout the centuries to help marginalised and oppressed people reconnect with their roots.

Music and song can serve as a potential conductor for these lost insights. This is often unseen within the more capitalist bastardisation of music: as something meant to have a mass appeal. On top of that, Radyo Siwèl’s roots in folk tradition were positively queer, adding a whole new dimension to sexual identity from a Haitian point of view. Laveaux, as a queer artist, was able to explore notions of her own sexuality within these old-fangled songs. (It’s important to note that I learned from her music that Creole is inherently queer as a language, with just a single pronoun, and actually a linguistic tool used to help unshackle Haiti from its longtime occupation.)

Indeed, there’s a lot to unpack when it comes to discussing Mélissa Laveaux’s body of work, and Mama forgot her name was Miracle feels very much like a vine naturally growing out of Radyo Siwèl’s seed. Laveaux’s infectious mix of Carribean music, calypso, dancehall, psych rock and post-punk is flamboyant, joyous and outgoing in both its color and cadence. Lyrically, however, these songs carry an almost mantra-like quality, expressing a strong personal yearning to reconcile activism with positive forward momentum.

Similar to Sons Of Kemet’s monumental Your Queen Is A Reptile, Mama forgot her name was Miracle insists on enshrining historical figures who have been erased or forgotten for their courage and resilience, acting as guiding lights for Laveaux to communicate with the outside world. She never does so in a fraught, expositional way, using the mischief and hook-heavy jargon of mainstream-minded pop to cause a splash.

Like Yaya Bey did last year, Laveaux – for example – borrows and repurposes Megan Thee Stallion’s irreverent “I’m a bad bitch”-catchphrase on “Half A Wizard, Half A Wizard”. Alternately, the song’s melodic progression reminds me a wee bit of Nick Drake’s solemn, introverted gem “Fruit Tree”, as well as the crispness in Laveaux’s lyrical delivery. It all feels executed with playful indulgence: ‘Let’s see if I can roll out this super intimate folk thing all the way to a full-on Adele-styled nocturnal pop belter?’ The song references author Alice Walker’s essay In search of our Mothers’ Gardens, which talks about how mothers often had to abandon their own dreams to nourish the dreams of their children. And in some ways it highlight the joys in ourselves, for silenced voices often spend the bulk of their lives surviving and processing trauma. This theme again ties back to the purpose of music outside of the bright lights, its purpose to generate compassion and care is rarely immortalized in records or articles, though arguably more urgent than anything else.

Comparable to Kendrick Lamar’s seminal album closer “Mortal Man”, Laveaux reconciles different non-linear narratives that inspired her under a single sonic umbrella. The trip hop-inflected “Fire Next Time” references freedom fighter Harriet Tubman and author James Baldwin, as Laveaux sings “every breath you take is a prayer”.

“Faith Meets Ana” imagines a conversation between artists Faith Ringgold and Ana Menieta had the latter not met a tragic end by defenestration. Its faint vocal yelps and warm handclaps serve as an alleviating agent, as it’s quite a devastating song, given the two protagonists’ ruptured fates. Laveaux’s free-associative poetry of fiction and reality culminates on the night cruising, Devo sounding wave pop of ”Storm Helen, Storm Caster”, sung from the perspective from Olympic runners Helen Stephens and Caster Semenya.

Though Mama forgot her name was Miracle really embraces Laveaux’s full range of musical interests, it does suffer a little bit from congestion. What made Radyo’s Siwèl one of my favorite albums of 2018 was how that record’s imperative felt implicit and hyper-focussed. Laveaux’s overriding mission was to uncover some of the static of her own background, allowing the story behind each track room to breathe. Mama forgot her name was Miracle is a wee bit murky and impulsive in its chosen subjects: it wants to communicate a lot to the listener, and as a result, the weight behind these songs tend to cancel each other out.

That said, from an individual standpoint, these are some of Laveaux’s most stunning songs period. Especially “Rosewater”, featuring the velvety voice of November Ultra, combines experimental jazz grooves with starlit piano flourishes by Guillaume Ferran: so beautifully played that the arrangement could almost stand on its own.

Perhaps Mama forgot her name was Miracle could have benefitted from one or two fewer tracks, but Laveaux succeeds wholly in further fleshing out her songwriting potential with the goal to bring to light historical testimonials that need to be dusted off. When push comes to shove, Laveaux’s high-wired juggling act of reconciling the intimate quality of the lullaby with the outward bluster of pop is downright courageous and philanthropic. You may even call it miraculous.