Déjà Vu possesses the incantation and fleetingness of a comet that shines its brightest light before going out

1970 is often regarded as a transitional year for popular culture in general, and music is obviously no exception. With the collective dream of the previous decade having quickly turned into an unpredictable nightmare, pop tended to reflect its own self-sabotaging by seeing bands breaking up and artists burning out, while a sense of narcissism and self-importance grew amongst the new countercultural elite, now fully aware of its social status and rich enough to hedonistically indulge in whatever new artistic endeavour sounded remotely exciting.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young‘s Déjà Vu is a reflection of this fascinating implosion, offering both a glimpse of a uniquely magical moment in time and the unmerciful portrait of four egos running away with one another. After all, it was always inevitable that an organism as powerful as this gathering of giants would self-destruct from the inside, and if relationships were already fragile (to say the least) on the previous year’s Crosby, Stills & Nash, Neil Young joining the mix meant, as Barney Hoskyns puts it, “a whole extra dimension of danger and unpredictability”. The Canadian musician’s interaction with former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Stephen Stills had already proven to be anything but smooth.

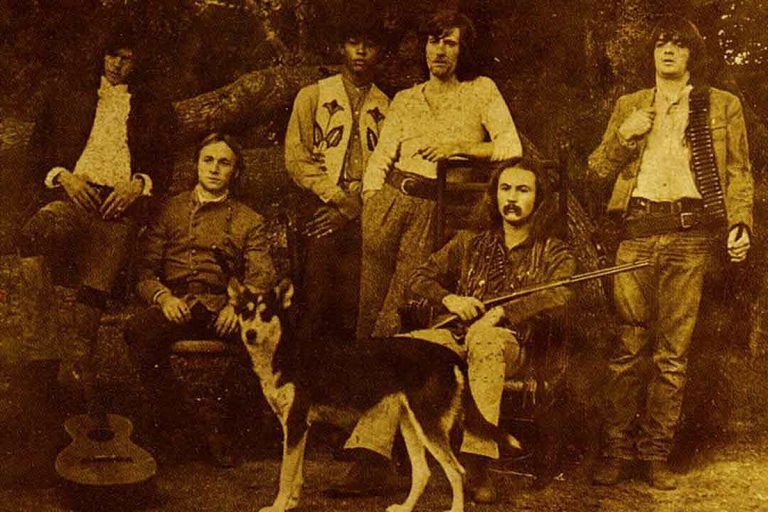

Stills was otherwise very much convinced he was the leader, something Crosby confirms by recalling that most of the friction during the album’s recording process came exactly from Stills’ interactions with the others. But drugs also played a major part in the equation: session drummer Dallas Taylor (who appears on the cover along with Greg Reeves) points out how common heroin was at the time — whilst Stills was also obviously feeding an already considerable paranoia with cocaine. An obsession with perfection made the recording sessions (which were mostly conducted as individual slots for each member) last for half a year, the album eventually emerging from this vortex of quarrels. “The wall that Elliot Roberts erected around the sessions for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Déjà Vu only made the competitiveness between the four men the more claustrophobic,” Hoskyns adds.

Déjà Vu possesses the incantation and fleetingness of a comet that shines its brightest light before going out. Remaining each member’s most successful album to date, it is so uncannily put together one would say the work of some sort of deity channelled through the energy generated by this meeting of titans — this was, after all, one of the first (if not the first) American supergroups.

Its impact impossible to match or replicate, Déjà Vu and its making represent a turning point for counterculture in general and rock in particular when everything started to rot from the inside, killing the last traces of optimism the 60s had desperately tried to cling onto, and opening the flood gates to the egotistical 70s — a process very much represented by the constant bumping of four heads in a stubborn, narcissistic manner, painfully reminding us of the slow death The Beatles would publicly broadcast that same spring in the form of Let It Be. The album, as Hoskyns would later describe it, “represented the death of rock innocence”.

There is a fine line that is still navigable in Déjà Vu, but would prove too fragile to sustain for much longer, drawn between individualistic artistic whims and complete surrender to perfect symbiosis; after all, each of the four musicians’ contributions were undeniably personal and recognisable in both their sonic and lyrical forms. While Nash’s “Teach Your Children” and “Our House” spoke of an idyllic (and therefore fantasist) view of life in the Canyon, Crosby’s compositions reflected a hedonistic stoned cynicism which would become a bit of his trademark in the coming years. Add Stephen Stills and Neil Young both pushing for control of the superorganism whilst simultaneously pulling it in two different directions (genius as the two might be, “Helpless” and “Carry On” are miles away from each other), offering but a brief glimpse of what an agreement could sound like in “Everybody I Love You”. The omnipresent tension that brilliantly ties everything together is underlined by the inclusion of an electric version of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock”, treated in the most respectful manner and seeing the four musicians in a rare “all parts equal” equation in what comes to each member’s contribution to a Déjà Vu track.

Alleviation from this outer worldly firecracker came under the form of the four members’ solo albums, released in the immediate aftermath of the crumbling of this colossus. These seemed to embody everything each one individually wanted to say in Déjà Vu yet hadn’t, but inevitably left contemporary critics slightly underwhelmed — probably due to the stark contrast when juxtaposed to the puissance of the collective. Looking back, it’s still hard to believe such a gathering ever took place and managed to bear fruit, especially if one takes into account the amount of unpredictable variables playing out at the time; but karma sorted itself out, and the endurance and geniality of Déjà Vu resides exactly in its ability to sound like a Machiavellian form of group therapy.