Paul Simon, Miriam Makeba, and members of Ladysmith Black Mambazo at a concert in 1987. Photo by Luise Gubb.

I was drinking heavily on the night of May 25th when I received a text message from BPM guru Evan Kaloudis. It said, “Hey- you like Paul Simon, right?” At the time, I liked everyone, everything, and everyone’s things, so my reaction was something like, “Shit yeah!” or, “Damn straight!” or, “Pour me another.” In any case, the next morning, when I was looking through my messages from the night before for anything incriminating, or at the very least anything that indicated what had happened to my shirt (still missing in action), I came across the conversation. Apparently, I was to cover a screening of “Under African Skies,” a documentary about the Paul Simon album Graceland, which, until then, I had never heard of, though I had neglected to mention that to Evan the evening before. Oh, yes, and there was to be a Q&A session with the man himself after. I guess he assumed that I loved Paul Simon because of my known obsession with folk and Americana, but at the time my only experience with him had been when someone put on “The Sounds of Silence” in a smoke filled dorm room my freshman year of college. The choir boy-ness of it bothered me, and so I dismissed the man entirely. Obviously I had some catching up to do. Luckily, my current means of employment consists of five student workers sitting in front of one phone that rings once or twice an hour, if at all.

I started with his debut, Paul Simon. What a glorious album. A glorious album that is, unfortunately, almost entirely irrelevant to this review. [Editor’s Note: We’re going to make him do a Second Look]

Err, right, so, Graceland. Graceland is awesome. Listen to it. Thanks in no small part to Vampire Weekend, the idea of white kids from New York City ripping off Afropop might seem a little less than unique, but man, Paul Simon was the original white kid from New York City, and he did it right. Rhythmically, the album is superb. The South African musicians play with a smooth intensity that sounds as fresh now as it must have in 1986, and the African vocalists are blast to listen to, even though I’ll never have the faintest idea what they’re talking about (which, as it turns out, Paul Simon himself isn’t so clear on, either). I won’t waste too much time talking about the album, since this is supposed to be about “Under African Skies” and the Q&A that followed it (I’m getting to it; I swear), but needless to say, you should listen to the album, and you should go buy the new release of it, and I will explain why:

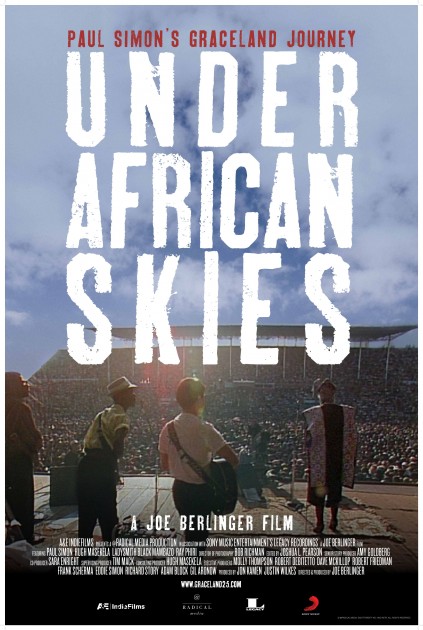

Because every copy of the 25th anniversary edition of the album comes with “Under African Skies,” a wonderful documentary by Joe Berlinger on the creation of the album and the controversy surrounding it. For those unfamiliar (as I was) with the album, Paul Simon broke the UN’s cultural boycott of apartheid South Africa by going there to record with black musicians whose music he had become acquainted with via a cassette tape by the Boyoyo Boys, a band that achieved much success in its home country but was largely unknown to the rest of the world. So what’s a guy to do when he’s coming off the relative failure of his last album and looking to record another? Why, travel across the globe to record backing tracks with some dudes whose cassette got handed to you, of course!

And so he did. The recording process for Graceland was fascinating, and the footage from the sessions is a wonderful document of the bazaar creative process. Basically, Simon called up a producer in South Africa who then recruited the band Stimela to come into the studio. There, Simon let the band jam for hours, stopping them when he heard something and interjecting directions. Back home, Simon and his producer listened through the tapes and eventually edited hours of loose jams into cohesive songs with actual structures, a process that, according to Simon, “would have been a lot easier with ProTools.” After the backing tracks were finished, Simon wrote and recorded melodies and lyrics over the South African musicians, while also inviting Ladysmith Black Mambazo, a South African a cappella group, to add their own unique vocal flavor to the album. All of this resulted in Graceland, a remarkable album with a character really unlike anything else. The lyrics and melodies are typical of Simon’s other work, but the music behind them is a far cry from the gentle fingerpicked guitar that backed them up in the days of the dynamic folk trio Simon and Garfunkle and Garfunkle’s hair.

The documentary is similarly excellent, and the interviews with Simon and the African musicians (who had never heard of Paul Simon) that played with him are quite revealing and frame much of the narrative.

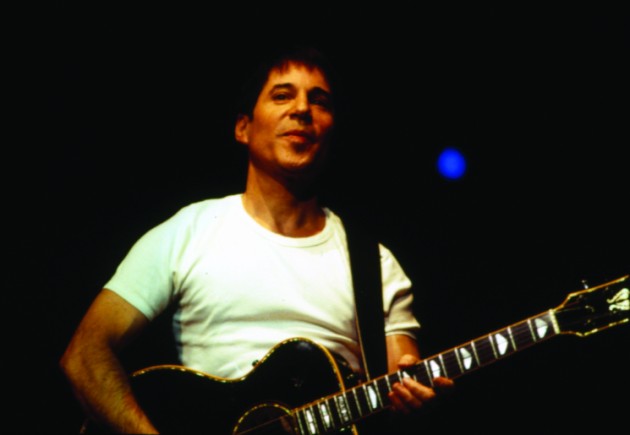

Paul Simon, 1987. Photo by Harrison Funk.

All the more interesting is the controversy that erupted after the album was released and became a bestseller. To those of us that were born after apartheid had run its course, the idea of a “cultural boycott” seems pretty strange. Why deprive a people that are already being deprived of so much of an opportunity to share their music on a global level? That was Paul Simon’s thinking, and I’m inclined to agree with him. I find it hard to believe, as the African National Congress contended, that Paul Simon recording an album with black musicians in South Africa somehow helped contribute to the continuation of apartheid. The musicians themselves felt the same. At a press conference, one of the African musicians, in response to strong criticism of Simon’s breaking of the cultural boycott, angrily demands, “What the fuck have you ever done for Africa?” That’s a damn good question. The people that boycotted the album will have a hell of a time coming up with any sort of evidence that the release of Graceland somehow hurt the cause of ending apartheid. What we do know for certain from the seven and a half million albums sold is that a hell of a lot of people were exposed to the culture of the oppressed black South Africans as a direct result of Simon’s work, and I struggle to see how that could do anything but help their cause. Included in the documentary is a tape of a modern day meeting with one of the anti-apartheid activists and the musician himself. Even the activist had trouble justifying his boycott now, saying only that, “At the time, your actions were not helpful.” I disagree.

The Q&A was a bit disappointing, as the audience was not invited to ask questions. Instead, we listened to Bob Costas ask Simon questions that he had mostly already answered in the documentary. Costas played hardball with director Joe Berlinger, asking him such doozies as, “are you happy with how the film turned out?” and, “how many people do you think will see the documentary?”

The only real noteworthy moment was a question to Simon about the decline of his audience’s numbers. Obviously, not as many people heard 2011’s So Beautiful or So What as Graceland or Paul Simon (though the album did sell a quarter of a million units in the US alone, which in these years of declining record sales is damn impressive). Simon was silent for a moment, then responded, “It’s much harder to get people to hear it. It’s disappointing, really.” Still, Simon expressed contentment with his career today, and ended his response with “It’s just not a contest.”

It’s not, but if it was, I imagine Paul Simon would be doing much better than most. If you don’t have a copy of Graceland already, buy the reissue, and if you do, buy it anyway. Joe Berlinger’s “Under African Skies” makes the package well worth the price of admission.