It was snowing in thick, oppressive sheets on Tuesday night, which I found all too appropriate as I walked down Delancey to see Savages play the Bowery Ballroom. Chilling weather for a night of chilling sounds.

Savages’ reputation precedes them, and that’s an awfully tricky situation. When a band’s live persona is built upon the expectation of a harsh, confrontational experience, the expectation itself runs the risk of neutering any genuine shock. The description from their homepage, recently updated in advance of their upcoming debut LP, reads: “SAVAGES is not trying to give you something you didn’t have already, it is calling within yourself something you buried ages ago, it is an attempt to reveal and reconnect your PHYSICAL and EMOTIONAL self and give you the urge to experience your life differently….” Their old description was less about the “physical” and “emotional,” and more about “aesthetics” and “design” — which is all well and good for the abstract of a Eugene Lang thesis project, but not so much for a band. Was Savages’ live show going to be an art school project, or was I going to have my soul beaten like the kick drum that pulses through most of their tracks?

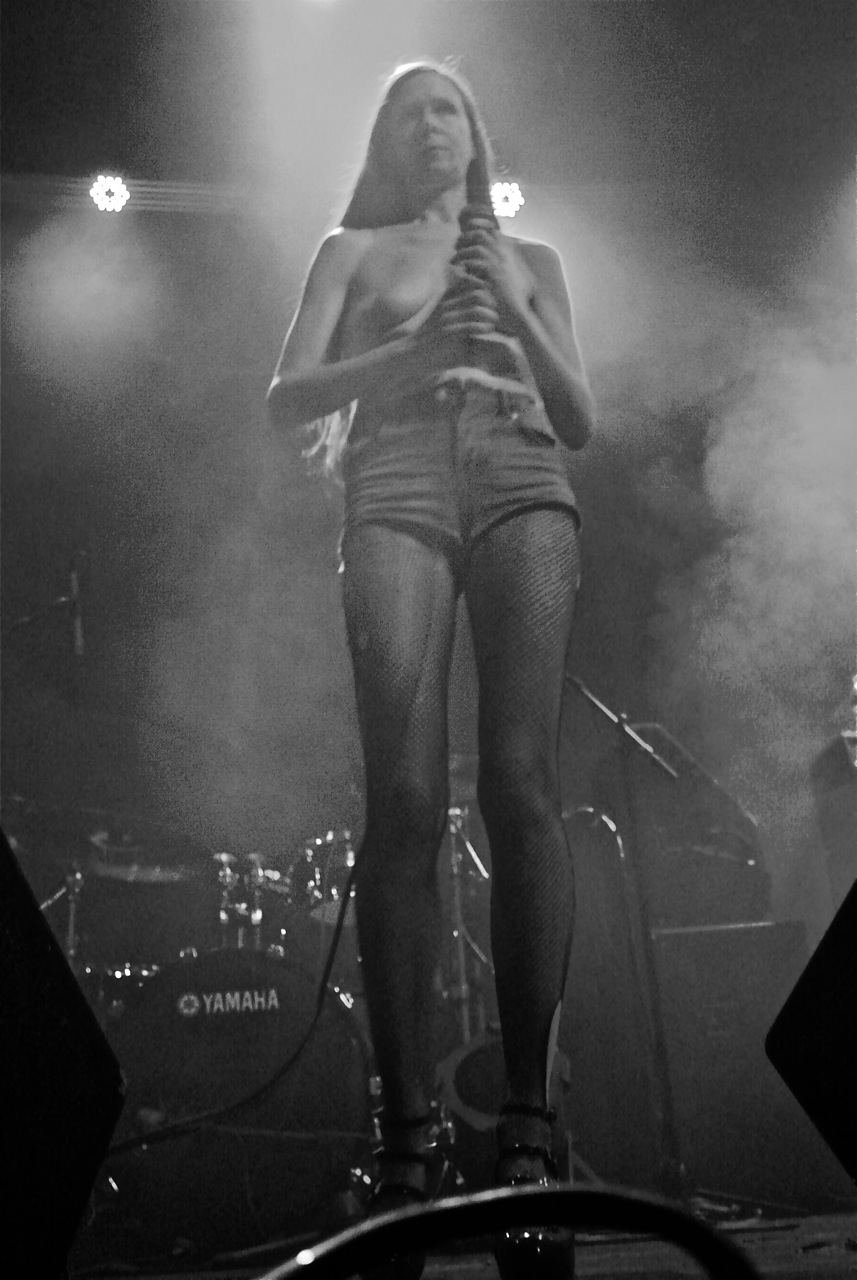

When No Bra began her set, I was inclined towards the former. I struggled to make out the words of the tall, murmuring figure standing stock-still before me — what with the industrial beats from her Macbook chugging over her poetry. I wondered if I was trying too hard to “get it.” Then she calmly took her top off and continued to bob her head to the music.

Okay, I thought, I think I get it. Objectification, alienation, and so on–song titles like “Doherfuckher” make that pretty clear. But is “getting it” enough on its own? Was I supposed to feel something more? A woman in the crowd shouted, “I wanna lick your boobies!” and I wondered whether I was thinking too much or if she was thinking too little. (No Bra responded: “Oh, great, come on up!” She didn’t.)

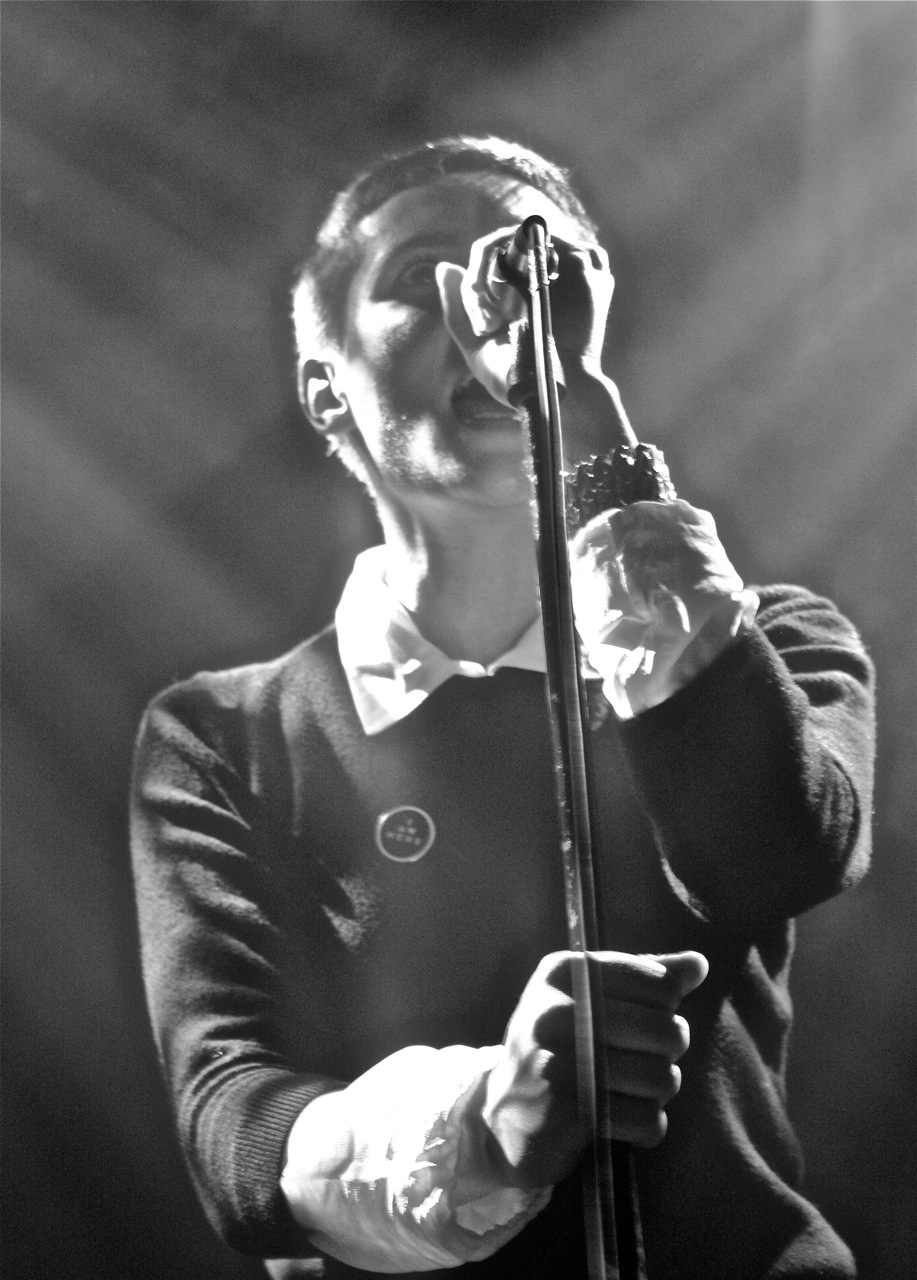

The contrast between No Bra’s deliberate anti-theater and Savages’ rollicking feminist fury was about as black and white as the band’s press photos. Jehnny Beth’s manic stage presence proved a more than worthy successor to Siouxsie Sioux (even without all the eye makeup). Watching her prowl behind Gemma Thompson with eyes as wide as a cat’s, you’d nearly expect her to pounce — which made it all the more surprising when she simply laid her arms on the ever-stoic guitarist’s shoulders in a gentle embrace.

The rhythm section, with their less dramatic demeanor, humanized the band somewhat. Bassist Aysse Hassan’s downright cheerful grooving was unexpectedly endearing, as was drummer Faye Milton’s expression during more her demanding fills — which I can only describe as her “GET SOME” face.

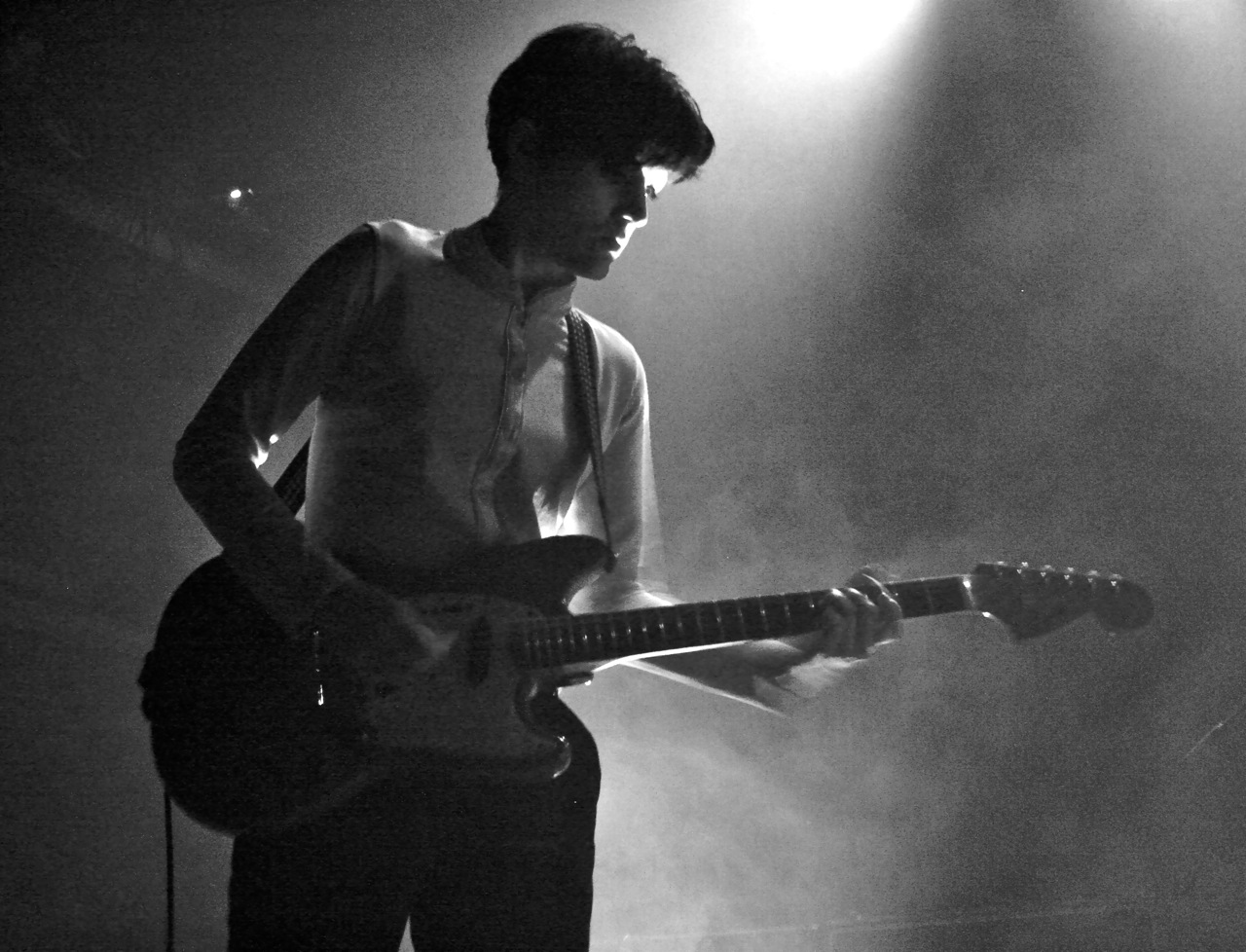

The music itself was similarly marked by contrasts, all buzz saw blasts of distortion cutting between measures of clean, pulsing rhythm. Savages have managed to push the the palpitating aesthetic that made “Husbands” into a more flexible instrumental framework; smoldering guitar solos emerged throughout the set, and slower numbers like “Strife” were pushed along by surprisingly funky bass lines.

Yet, much in the way that Jehnny walked along the edge of the stage midway through the set, Savages may soon find themselves on a tightrope walk. For the moment, they are a group with a fresh vitality, one of the few post-punk influenced outfits who have managed to capture post-punk’s most important element: urgency. Savages exude a seething restlessness within modern culture that goes largely unaddressed in modern music, and for that they just might prove a deeply important band.

But the technical difficulties Gemma experienced during “Husbands,” the closer, revealed the immense pressure that their strict creative guidelines might impose in their early stages. The crowd cheered encouragingly and clapped in rhythm as she hastily fumbled with her effect pedals, then ran back to check the amp; Jehnny grew more and more impatient with each false start and vamped measure; Faye lashed her cymbals with extra vigor to compensate for the absent distortion, which was enough for the crowd, but not for Gemma, who tossed her guitar aside and strode offstage a beat early. We, the audience, found it forgivable — we “get” the message well enough, and we get that these are simply people playing music up on stage. The performance doesn’t need to be perfect for it to resonate. We can forgive a break in the illusion. One can only hope the band can forgive themselves from time to time. Even Siouxsie Sioux has a sense of humor.